In the years before and after 1900, the gender bias made it far more difficult than it is today for women to be taken seriously as composers. In order to break into the then thriving market for new songs, many female songwriters and composers achieved success by resorting to one of two gender-obscuring strategies: choosing a man’s name as a pseudonym or replacing their first names with initials. Those who chose a male name and stuck with it for many years took part in the same subterfuge employed successfully by many women writers. They followed the examples of 19th-century women writers like Amandine Aurore Lucile Dupin de Francueil (George Sand) or Mary Ann Evans (George Eliot), or today, J. K. Rowling writing as Robert Galbraith.

But numerous other women obscured their gender without resorting to pseudonyms, instead hiding behind their initials. I am doubtless not alone in having assumed that P. D. James was a man, discovering only later that this is how Phyllis Dorothy James White, Baroness James of Holland Park, preferred to be known as a writer. The explanation Charlotte Brontë provided for why she and her sisters became Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell applies to initials as well: “we did not like to declare ourselves women, because … we had the vague impression that authoresses are liable to be looked on with prejudice” (Langland, 391).

At the end of the 19th century, a nationally syndicated newspaper article about women songwriters addressed the prejudice directly, outlining the problem in the headline and subheaders: “THEY WRITE MUSIC // New York Women Who Profit By Melody // They Are, However, Forced by Prejudice to Use the Names of Men – Their Productions Would Not Sell So Well Otherwise (Ann Arbor Daily Courier, 6 Aug. 1895). The writer cites the example of Mrs. Edward Lawson Purdy, who signed her songs as M. McCracken Purdy, without explaining that her birth name was Mary McCrackan.

This is just when Emma Louise Ashford began to produce the first of her many hundreds of compositions, all as E. L. Ashford, a name that even fooled one who should have known better: “It is rather interesting to note that one of her publishers thought that E. L. Ashford […] belonged to the masculine half of humanity, and was astonished when, after many months, the ‘My Dear Sir’ to whom he frequently indited letters turned out to be a frail little woman of the most distinctly feminine type” (Gilchrist, 88).

In choosing to initialize their names, whether just one initial or two, these women had distinguished company. A list of the most eminent includes the following. The first parentheses record the total number of published songs, then comes nationality and lastly, life span. The names are ordered chronologically according to year of birth:

Clara Angela Macirone as C. A. Macirone (47) (UK) (1821–95)

Amelia Lehmann as A. L. (55) (UK) (1838–1903)

Catharine Adelaide Ranken as C. A. Ranken (49) (UK) (1841–1918)

Martha Theodora Frain as M. Theo. Frain (25) (USA) (1844–1929)

Emma Louise Ashford as E. L. Ashford (130) (USA) (1850–1930)

Annie Frances Loud as A. F. Loud (37) (USA) (1856–1934)

Cora S. Briggs as C. S. Briggs (33) (USA) (1859–1935)

Agnes Helen Lambert as A. H. Lambert (29) (UK) (1860–1929)

Charlotte Milligan Fox as C. Milligan Fox (51) (IRE) (1864–1916)

Isabel Hearne as I. Hearne (31) (UK) (1864–1933)

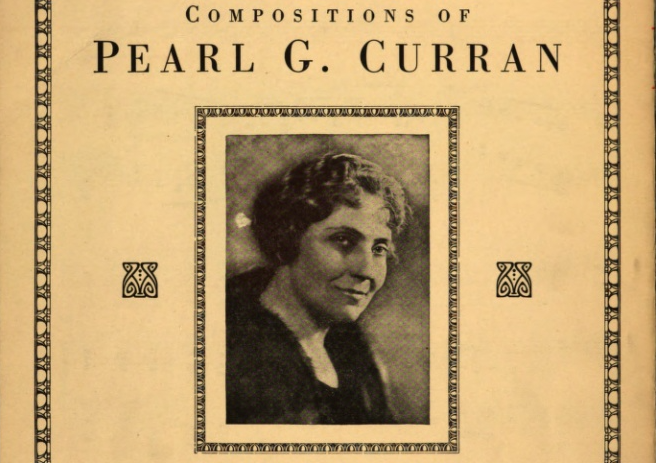

Pauline B. Story as P. B. Story (63 of 93) (USA) (1870–1952)

Ariadne Holmes Edwards as A. H. Edwards (23) (USA) (1875–1940)

Elsa Wyman Maxwell as E. Maxwell-Wyman (8 of 63) (USA) (1881–1963)

Henriette Blanke Belcher as H. B. Blanke (12 of 33) (USA) (1882–1958)

Gloria Marshall Loepke as G. Marschal-Loepke (33 of 48) (USA) (1884–1976)

The women in this list fall into three loose stylistic categories: arrangers of folk music (women who also composed some middlebrow pieces), middlebrow, and popular (including dance music and ragtime piano pieces).

Arrangers of Folk Music

A. L. – Signing herself only as ‘A. L.’, singer and composer Amelia Lehmann moved in the most exclusive artistic circles of her day. Her father was the Scottish writer and publisher Robert Chambers, author, among many other things, of the five-volume History of the Rebellions in Scotland; with his brother he brought out the Chambers’s Encyclopaedia, issued by their firm, W. and R. Chambers Publishers in Edinburgh. Her parents were close to Charles Dickens, Robert Browning, and Mary Ann Evans (George Eliot). She married Rudolf Lehmann, society portrait painter and author, and their social world included the painters of the Holland Park Circle and musicians such as Joseph Joachim and Pauline Viardot Garcia. Their daughter Liza Lehmann Bedford became the most successful woman songwriter of her generation.

Lehmann produced at least 61 songs, mostly arrangements of folk songs and songs from earlier centuries. Her arrangement of Thomas Moore’s “When Love Is Kind,” enjoyed a sustained popularity. Lucrezia Bori recorded it in a version for orchestra (1922).

C. Milligan Fox – Irish composer and ethnographer Charlotte Milligan-Fox contributed significantly to the revival of interest in the Irish harp and Irish song. After studying music at Conservatories in Frankfurt, Germany, and Milan, Italy, and at the Royal College of Music, London, she settled in London. There she co-founded the Irish Folk Song Society in 1904 and published her volumes Songs of the Irish Harpers (1910) and Annals of the Irish Harpers (1911), as well as articles in the Journal of the Irish Folk Song Society.

Together with two of her sisters Edith and Alice, she travelled through Ireland transcribing and recording songs they heard. Among the dozens of songs she arranged was a Donegal air she used to set a poem by Nora Hopper Chesson, “By the Short Cut to the Rosses,” which John McCormack recorded in 1928. McCormack was particularly attached to “The Foggy Dew,” recording it in 1913, in 1924, and again in 1928. The recording in 1924 took place in the triumphal concert he gave in Queen’s Hall, London, his first appearance in England since the British government had decided to restore his rights to re-enter the country. Although he sang Chesson’s older poem, listeners would have recognized that with newer words, the song had become a passionate cry for Irish independence.

Popular Music

H. B. Blanke – born in Kansas City, Henriette Blanke moved to Detroit, then New York City, signing her earliest compositions between 1903 and 1907 as H. B. Blanke. The early and substantial success of her own songs and piano waltzes came in the decade she spent as a staff composer for the Detroit-based publisher, Whitney-Warner. In 1905 she married Fred Belcher, the New York City manager of the other big Detroit firm, Jerome H. Remick & Co. Their wedding was reported nationally, “a brilliant affair” attended by many of the most illustrious songwriters of the day: the duos (William) Jerome and (Jean) Schwartz, and (Harry) Williams and (Egbert) Van Alstyne, as well as Charles M. Daniels, James O’Dea and Maude Nugent.

One of the songs she wrote that year was “When the Mocking Birds Are Singing in the Wildwood.” Two years later she began to identify herself with her married name, Henriette Blanke Belcher.

E. Maxwell Wyman – Elsa Wyman Maxwell, from the small Mississippi River town, Keokuk, Iowa, eventually achieved her celebrity for the society parties she threw and for inventing the scavenger hunt (google her name together with “famed hostess”). Many of her 63 songs show much in common with the songs of her 10-year-younger friend and protégée, Cole Porter. Before she had established herself, she, or her publisher Witmark & Sons, produced eight songs by E. Maxwell Wyman. From then on – for her songs, her books, her radio show, her TV appearances – she became simply Elsa Maxwell.

The cultural visibility of her parties and her extravagant partying have completely eclipsed the significance of her songs. One of the few now available online is “Please Keep Out of My Dreams” (1925), sung by Frances Alda. Much easier to find, thanks to a modern reissue of her 1958 album, are Maxwell’s own spoken versions her songs, recited over an instrumental foundation, in a manner made familiar decades earlier by Carrie Jacobs Bond.

Women Song Sharks

It was not just unscrupulous men who made a living setting bad poetry that arrived in the mails, preying on would-be songwriters. The prolific composer Pauline B. Story, born and raised in Cincinnati, did quite well in this predatory niche market, though she barely managed to avoid prison. Story has a following today for some of her early ragtime piano works, but her songs are long forgotten. If that is true for the 30 songs she wrote under her full name – mostly before 1915 and many of them to lyrics by Robert H. Brennen – it is especially the case for the 63 songs she composed as P. B. Story, songs composed to lyrics by 52 different and unknown poets.

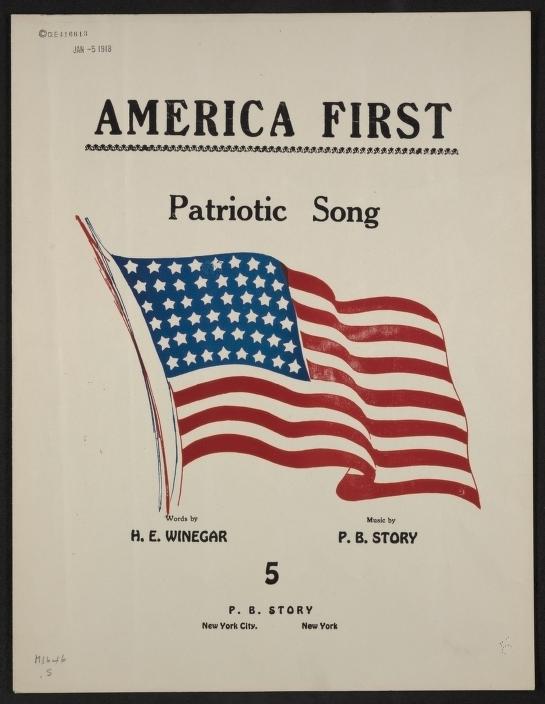

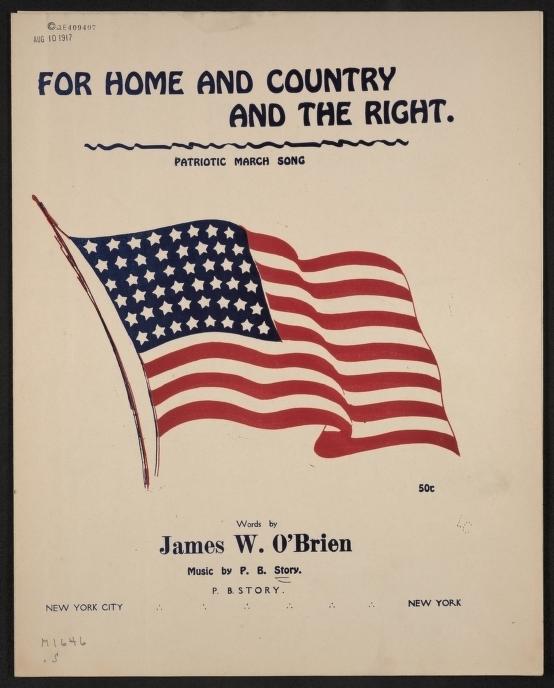

Some were issued by Frank Harding’s Music House in Manhattan, but starting in 1917 she published many herself. These include jingoistic World War I recruitment ballads such as “Gee, I Wish I Was a Boy,” “Get a Bond Boys,” “Justice First, Then Fatherly Love,” “For Home and Country and the Right,” “Down the Wrong and Raise the Right,” and “America First.” Her disregard for the quality of her products is evident in her recycling of generic and amateurish covers for different songs. Here are two:

Most of these songs were then self-published by the poet, with P. B. Story serving as a composer for hire. Indeed, several years earlier Story and her partner Robert H. Brennan had been charged with mail fraud for misleading naive songwriters with false hopes of wealth and fame. “MUSIC HOUSE IS FRAUD SAYS THE GOVERNMENT” (Washington Times Herald, 12 Nov. 1907): “The Post-office Department has issued a fraud order against the North American Music Company” of New York City. Stories nationally named R. H. Brennan and Mrs. P. B. Story as officers, accusing them of defrauding “amateur and inexperienced writers of music.” Brennan was eventually arrested (New York Tribune, 14 March 1908). The substantial profits they received were estimated to be more than $100,000 (Sioux City Journal, 5 Jan. 1908), roughly $3,400,000 in today’s dollars. No wonder song mills persisted; no wonder Brennan and Story found ways to continue offering their services for a fee.

Why did initials lose their appeal?

In the list of composers at the beginning of this post, the last three women resorted to initialed names only at the outset of their careers, evidently revealing their full names once they had proven their abilities. Belcher shifted in 1907, Maxwell in 1909, and Loepke after 1917. Pauline Story reversed this trajectory, evidently finding in mid-career that the cover of initials proved useful for dealing with clients in Bozeman, Montana, and other distant towns.

It would be tempting to think that the feminist wave of suffragism also swept in an era in which female composers didn’t need to shield their identities. But if the impetus for women to mask their gender by means of pseudonyms or initials declined among composers, it has not disappeared among writers. The creator of Harry Potter shows the enduring earning power of old marketing strategies. Because Joanne Rowling’s advisors at Bloomsbury Publishing worried that teenage boys would balk at reading a woman author, she settled on two initials, her own and one that paired well with it (Kirk, 76). First as J. K., later as Robert Galbraith, Rowling has profited by effacing her gender.

For writers, this remains an issue. A perusal only a few years ago of “online forums where writers of fiction and poetry exchange tips on getting published revealed that women are often advised to use initials” (Cameron, 2021). Why would it be different for composers and songwriters? Because music needs to be performed, and living composers are often present? Would symphony orchestras be any more likely to perform works by women if the composers were identified by initials?

The answers to these questions and others doubtless vary according to nationality and also to the style of music. The diverse cultures of concert halls, Tin Pan Alley publishers, dance halls, and churches make any single explanation unlikely. One factor for American women writing tonal (light) classical music was the rise of women’s clubs. Their many regularly scheduled concerts actively promoted songs by women. In those vibrant circles, initials offered no advantage.

Notes

On women writers who used initials, see Debbie Cameron, “Women of Letters,” on the blog, “language: a feminist guide” (13 July 2021); and Catherine A. Judd, “Male Pseudonyms and Female Authority in Victorian England,” Literature in the Marketplace: Nineteenth-Century British Publishing & Reading Practices, ed. John O. Jordan and Robert L. Patten (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003).

The proliferation of pseudonyms and initials in the 19th century also saw the rise of studies that attempted to identify the individuals behind the names, such as John Edward Haynes, Pseudonyms of Authors, Including Anonyms and Initialisms (New York, 1882), and William Cushing, Initials and Pseudonyms: A Dictionary of Literary Disguises, 2nd Series (New York, 1888). More recently, see Jeanette Marie Drone, Musical AKAs: Assumed Names and Sobriquets of Composers, Songwriters, Librettists, Lyricists, Hymnists, and Writers on Music (Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 2007).

In addition to P. B. Story, another prolific songwriter for hire was Ethel Fisher. In the decade from 1915 to 1925, she assumed nine different male names, several of them French, as she published 55 songs for as many amateur poets. Nothing is known about her, other than that she worked with four different New York firms, chiefly with Frank Harding’s Music House in Manhattan. She adopted the following pseudonyms: Carl (also Karl) Muehling from 1915 to January 1919, M. Du Frerre from 1918–20, Frank Lorraine – 1919, Louis Lamont – 1919–20, Gustave Barto – 1920–22, Max Norworth – 1921–22, Ray Ross Frampton – 1922–23, Jean Navarre – 1922–23, and, most frequently, Herman Dubois (also DuBois and Du Bois) – 1923–25. Details for her and for all others are available in my women’s song database.

Male song sharks are discussed in Part 1 of this post. I have earlier WSF essays that discuss Liza Lehmann and E. L. Ashford.

Other sources cited are:

Elizabeth Langland, “The Receptions of Charlotte Brontë, Charles Dickens, George Eliot, and Thomas Hardy,” A Companion to the Victorian Novel, ed. Patrick Brantlinger, William B. Thesing (Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 2002): 387–405.

Annie Somers Gilchrist, “Emma Louise Ashford,” in Gilchrist, Some Representative Women of Tennessee (Nashville: McQuiddy Printing Co., 1902): 83–91.

On the Lehmanns, Caroline Dakers, The Holland Park Circle: Artists and Victorian Society (New Haven: Yale UP, 1999): 135–36.

Ann Whitworth Howe, Lily Strickland, South Carolina’s Gift to American Music (Columbia, SC: R.L. Bryan Co., 1970).

Connie Ann Kirk, J.K. Rowling: A Biography (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2003).