There’s a sweet, sweet spirit in this place

And I know that it’s the spirit of the Lord

There are sweet expressions on each face

And I know they feel the presence of the Lord

Sweet holy spirit, sweet heavenly dove

Stay right here with us filling us with your love

And for these blessings, we lift our hearts in praise

Without a doubt we’ll know that we have been revived

When we shall leave this place

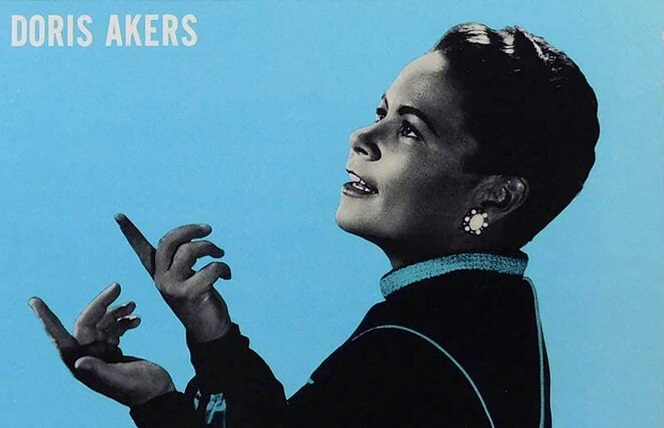

One of Black gospel’s most prolific composers, said to have written over 500 songs, Doris Akers (1923–95) was born in Brookfield, Missouri, where as a child she learned piano by ear, and in 1945 moved to Los Angeles, just before the modern gospel movement took full root in that city. Though also drawn to the swing music of her youth, Akers made her name as a church pianist, a choir director, and a lead in the nationally popular Simmons-Akers Singers, formed in the late 1940s in part to perform and record a rapidly growing catalog of songs that earned her the sobriquet “Miss Gospel Music.” Many of these, including “You Can’t Beat God Giving,” “Closer to Thee,” and “Lead Me, Guide Me,” remain standards.

Akers’s most famous song, “Sweet, Sweet Spirit,” published in 1962, shifts the customary focus on the individual “I” encountered in many Protestant hymns and Black gospel songs to the collective “we.” When hymns do broaden this personal testimony, it is usually to affirm of the bounds of Christian fellowship across time and space: “When we all get to Heaven,” “What a friend we have in Jesus,” “In the sweet by and by we shall meet on that beautiful shore.” But Akers further intensifies these communal feelings by localizing the song’s “we,” drawing a perimeter right here around this place and these faces, lingering in a moment that will last only until this congregation on this day departs. “Sweet, Sweet Spirit” has entered international acapella repertory through an arrangement by Australia’s The Idea of North—covered by others, including the Korean family group Ruah Worship—with close harmony that savors the intimate rub of Akers’s striking three-chord progression spotlighting the word “place.” There is an inside carved out and marked by “Sweet, Sweet Spirit,” felt most intensely through collective singing that activates the renewable affinities of familiar confines and company.

In her work as a gospel musician, Akers actively sought a place for her music both within and beyond Black congregations. Responding to a burgeoning interracial church movement in postwar Los Angeles, she founded the mixed-race Sky Pilot Choir, recorded as a soloist with popular white gospel quartets like the Statesmen, and partnered with Manna Music, launched in 1955 by cowboy singer Tim Spencer, as the exclusive distributor of her songs. These associations led gospel historian Jacqueline DjeDje to describe Akers as “the first to bridge the gap between black and white gospel music.” Though she is an inductee into the Gospel Music Hall of Fame and a Smithsonian honoree, her crossover career has largely slipped through the cracks of gospel history and memory. The light-skinned Akers’s reception is frequently framed by implicit, though sometimes explicit, acknowledgement of a politics of pigmentation. At a 2020 concert of traditional church songs, Marvin Williams, introducing a tribute segment, told his African American audience: “I know you all are thinking: ‘What does a white woman have to do with our service tonight?’ Well, Doris Akers was Black. Now, I’m dark chocolate. She’s white mocha. But she’s coffee all the same.”

Perhaps no Akers composition is more emblematic of her boundary straddling than “Sweet, Sweet Spirit,” one of a handful of songs by African American songwriters—Thomas A. Dorsey’s “Take My Hand, Precious Lord” and Kenneth Morris’s “Dig A Little Deeper” are two others—that have achieved canonical status across Black and white denominations. Akers herself recorded the song for her 1964 RCA album with the Statesmen, but in live performance it has become almost standard practice to render “Sweet, Sweet Spirit” while basking in room-warming homecoming nostalgia. This is apparent in Williams’s tribute set and in performances by artists like Linda Davis and Sandy Payton that invoke country music’s white southern rusticity. The consistency of affect across racially- and culturally-differentiated spaces—and the mobility of both the song and its composer—is evident when comparing mid-1990s performances by the older Akers at Bill Gaither–staged reunions of Black and white Southern gospel singers, respectively.

The cross-racial history of Akers and “Sweet, Sweet Spirit” may reasonably suggest a parable about the need for a corrective reboot, admonishing us about pernicious racial fictions that dissolve in actual practice. But the song’s migrations in fact call our attention to the persistent reality that Black and white congregations still largely worship separately, a reminder of the uniquely American co-presence of close proximity and chasmic distance in the racial legacies of U.S. churches and the nation.

Notes

Jacqueline Cogdell DjeDje, “Los Angeles Composers of African American Gospel Music: The First Generations,” American Music 11, no. 4 (1993): 412–57.

https://www.hymnologyarchive.com/doris-akers

Banner Photo Caption:

“The Sky Pilot Choir Directed by Doris Akers With The Sutton Sisters – The Sky Pilot Choir,” Christian Faith Recordings – SP-6041, Christian Faith Recordings – SK 6041 (1959) – cropped