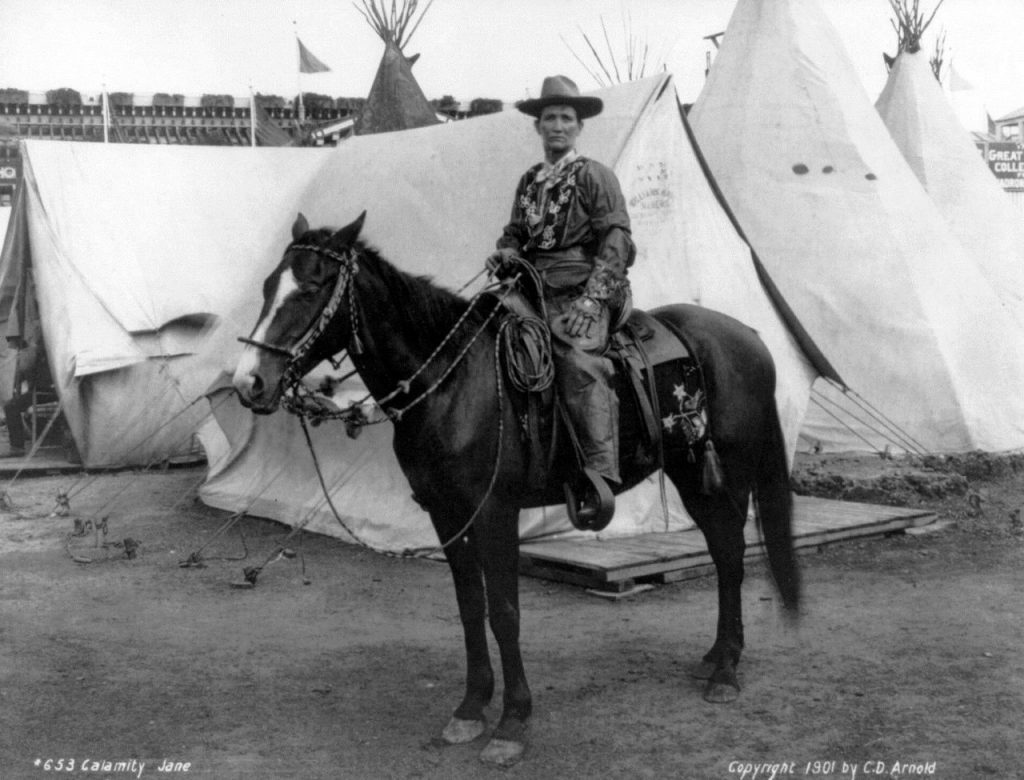

Claiming her place within American history, Martha Jane Cannary Hickok – ‘Calamity Jane’ (1852-1903) lived a life that, while not necessarily unique as an example of female determination and endurance, nevertheless captured female experience in action. Jane lived the majority of her life in the American ‘Wild West’, with a biography revealing a raw, dynamic, and challenging existence. Although tales of her hard-drinking and hard-living abound, her life was actually a complex dance between societal expectations and her own personal vision.

Her relationships with women and her role as a mother are less substantiated, yet arguably noteworthy. In her 1998 song cycle Songs from Letters: Calamity Jane to her daughter Janey, Libby Larsen explores the relationship between Jane and her daughter Janey (assumed with ‘Wild’ Bill Hickock). Through song composition, Larsen brings vital colour, body, and life-force to Jane’s texts.

The idea for this cycle emerged as a direct result of Larsen’s encounter with Karen Payne’s book Between Ourselves, a compilation of letters, throughout history, written between mothers and daughters. In particular, Larsen found inspiration from a quote by Rosa Luxemburg: “It is in the tiny struggles of individual peoples that the great movements of history are most truly observed” (Payne, 3). This became a fitting corridor of entry to Jane’s texts – words that reveal her desire not only to express her lived experience, as a woman living within a male-centric world, but to also share these stories with her daughter as an act of love, care, and maternal responsibility. As Libby Larsen explains it,

“In her time, she was odd and lonely. One hundred years later, her life sheds light on contemporary society. She uses rough-tough words to describe her life to her daughter. I’m interested in that rough-toughness and in Calamity Jane’s struggle to explain herself honestly to her daughter, Janey.”

Were the featured texts indeed Jane’s, or are they instead imaginary scenarios and conversations? It is most commonly thought that the letters were not sent to Janey during Jane’s lifetime, but rather existed in diary form and were discovered upon her death. Debate as to their authenticity also stems from the fact that Jane is believed to have been illiterate. Larsen – aware of this discrepancy – does not place undue importance on this possibility, stating “it doesn’t really matter; it is a real person and a real character” (Du Bon, 55). This cycle consists of five songs, designed to track the various stages of Jane’s life: So Like Your Father’s (1880), He Never Misses (1880), A Man Can Love Two Women (1880), A Working Woman (1882-1893), and All I Have (1902).

We find Larsen fully embracing the “colorful dramatization of her character … her warm and loving side in addition to her wild and rowdy personality” (Secrest, 23). Throughout, Larsen systematically paints a compelling picture of the intimate relationship, with her musical strategies allowing for a well-rounded, musically-led account of Jane’s lived identity. Featuring quasi-spontaneous discourse via markings such as ‘Freely, recitative’ (1 and 4), ‘With flexibility throughout’ (5), Calmly (3), and ‘With abandon’ (4), Larsen crafts a musical structure that supports the intimacy of Jane’s literary voice. Although the songs stand independently – in both design and content – the combined effect is one of a scena femina: microscopic accounts of lived female experience.

Larsen’s settings of the letters effectively elevate Calamity Jane’s words into poetry: “the text is where [Larsen] first begins in her compositional process, and from the text arises the music;” Larsen tends “to prefer prose, due to its flexibility in the process of text setting. Prose allows Larsen to create a sense of the natural flow of the words, enabling the listener to hear the music’s portrayal of qualities of American vernacular idioms” (Du Bon, 58). Larsen transports the listener to the heart of Jane’s private utterings. In her use of recitative and the omission of fixed time signatures, a sense of female connection emerges – an immediacy, a desire for communication, and a longing to be heard and understood.

However, it is through Larsen’s use of motivic invention, development, and repetition that the listener is afforded the opportunity to inhabit Jane’s world. The tritone stands as a central device, as “the metaphorical significance of being unsettled, being able to move in any direction” (Secrest, 23). As a vocal feature it represents the emotional contour of Jane’s life, as a pianistic device an opportunity to establish “the harmonic freedom [required] to move the musical material in any direction that the text calls for” (Du Bon, 59). Further, she omits key signatures, and fosters harmonic freedom by removing a formal tonal center, replacing it with musical cells that serve as metaphoric portrayals of the tensions and resolutions within Jane’s life. Her approach to melodic construction is that of creative exploration: a haven where voice and piano co-exist within textural, articulative, and expressive domains.

What might ‘Calamity Jane’ have made of Larsen’s song cycle? Jane explored her full, innate feminine self within a public arena – one where her audience (and critics) were predominantly male. Her historic footprint attests to a strong, fearless woman: capable and remarkably contemporary. Yet it is arguably through her letters that we are presented with a sweet paradox: an intimate glimpse of her vulnerabilities, her aspirations, her private emotional centre. Her daughter, as recipient, represents us as audience – one of female community and kinship. Larsen’s cycle invites the listener to consider Jane, via musical syntax and gesture, as a as an emotionally complete woman with a depth that her contemporary audiences never knew. I suspect that Jane would heartily approve.

But so too have impressively many sopranos. ‘Songs from Letters,’ has gained significant interest since its premiere in 1998 –emerging as a modern ‘hit’. The following list of YouTube video and commercially recorded examples attests to the cycle’s versatility, reach, and accessibility: Benita Valente (2000), Kathleen Roland (2002), Terry Rhodes (2004), Bonnie Pomfret (2006), Mary Elizabeth Southworth (2009), Adelaide Boedecker (2013), Susan Ruggiero-Mezzadri (2013), Joan Fearnley (2014), Tracey Engleman (2017), Claudillea (2017), Katie Harman (2017), Rachel Schutz (2018), Nim Lefcourt (2019).

Bibliography

Barks, C. Calamity Jane, Heritage Auctions (1978)

Du Bon, Meredith Taylor. Through the Ears of Libby Larsen: Women, Feminism, and Song in America. Indiana University: DMA Diss., 2014.

Payne, Karen. Between Ourselves: Letters Between Mothers and Daughters 1750-1982. London: Joseph, 1983.

Secrest, Glenda Denise. “‘Songs from Letters’ and ‘Cowboy Songs’ by Libby Larsen: Two Different Approaches to Western Mythology and Western Mythological Figures”. Journal of Singing: The Official Journal of the National Association of Teachers of Singing 64, no. 1 (2007): 21-30.