In the Autumn of 1927, contralto Marian Anderson left her home in Philadelphia and embarked on a year’s sojourn in London, marking the first of her many tours to Britain and wider Europe. She had resolved that further training with European specialists in art song would enable her to break through a feeling of artistic and professional standstill. Soon after her arrival, she began what she hoped would be a sustained course of lessons with the celebrated tenor and lieder interpreter Raimund von Zur Mühlen, who had emigrated from Germany to London before settling near the Sussex village of Steyning.

When Zur Mühlen became indisposed on account of ill health after just a few sessions, however, Anderson sought out several alternative teachers, one of whom was fellow contralto, vocal coach and composer Amanda Ira Aldridge. The youngest daughter of the African American Shakespearean actor Ira Aldridge and the Swedish opera singer Amanda Pauline Brandt, Amanda had been among the first students to attend the newly opened Royal College of Music in 1883, where she trained with Jenny Lind and George Henschel. After a bout of laryngitis limited her performing prospects, she relied increasingly on teaching, before entering the sheet music marketplace around 1907 as a composer of parlour and art songs, light piano suites and dances.

Prior to departing for London, Anderson was already aware of Aldridge’s “excellent reputation as a voice teacher,” having sought advice from fellow African American concert artists who had enjoyed success across the Atlantic (Anderson 1956, 127). Chief among these were Roland Hayes and his accompanist Lawrence Brown, both of whom had worked with Aldridge while residing in London immediately after the First World War. Aldridge also coached Paul Robeson and the baritone John Payne, whose home on Regent’s Park Road provided a welcoming hub for Black musicians and artists, Anderson included.

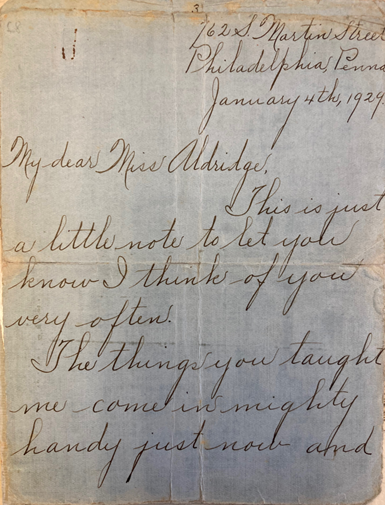

Aldridge was in her sixties by the time Anderson began visiting her for lessons at her teaching base at Weeks Studio in Hanover Square in January 1928. Returning to Philadelphia later that year, she wrote to Aldridge that “I think of you very often. The things you taught me come in mighty handy just now and all those people who have heard, feel that there is a decided improvement. I even yet regret that it was necessary to return to America so soon.” Aldridge, for her part, continued to follow Anderson’s blossoming career with great interest over the ensuing years.

As a vocal coach, Amanda styled herself as Miss Ira Aldridge, while as a composer she published using the male pseudonym Montague Ring. Although she was initially keen to keep her teaching and composing careers distinct, her professional identities increasingly overlapped as she gained a degree of recognition. Not only did she perform her own songs and piano pieces in recital, but she advertised her teaching credentials alongside lists of her available compositions. She also made strategic use of dedications in her published songs by referencing her associations with notable performers. She composed “A Noontide Song” especially for Hayes, who performed it at the Wigmore Hall in 1921; and she dedicated “Summah is de Lovin’ Time” (with lyrics by Paul Laurence Dunbar, 1925) to Paul Robeson and his wife Essie.

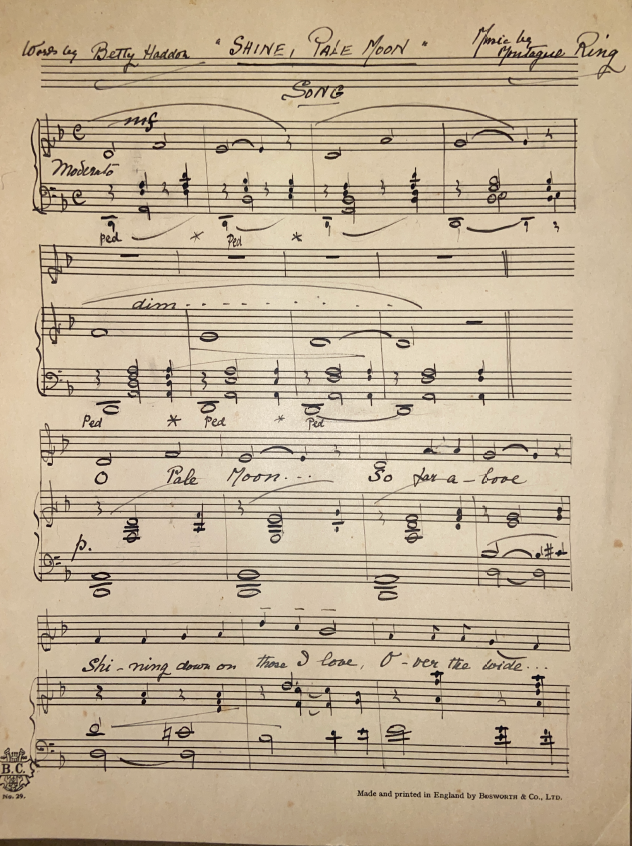

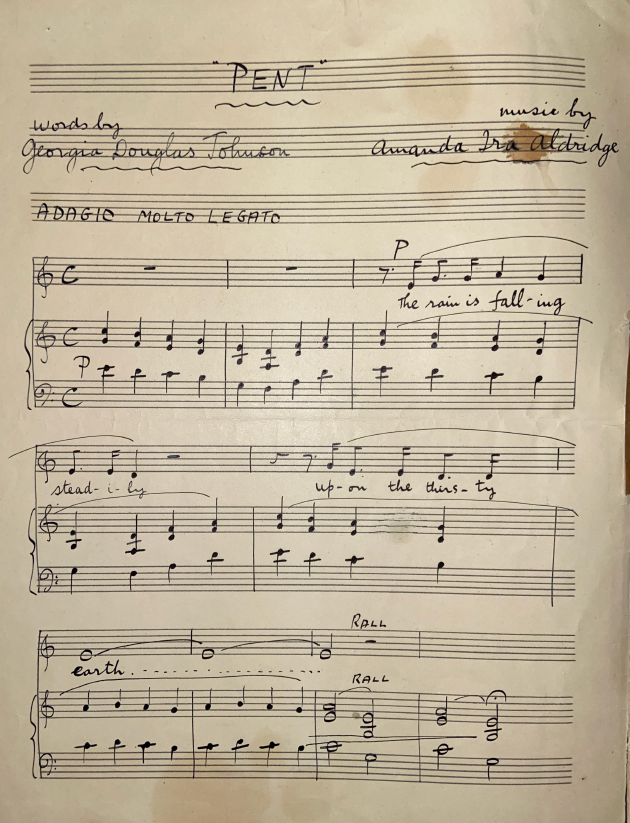

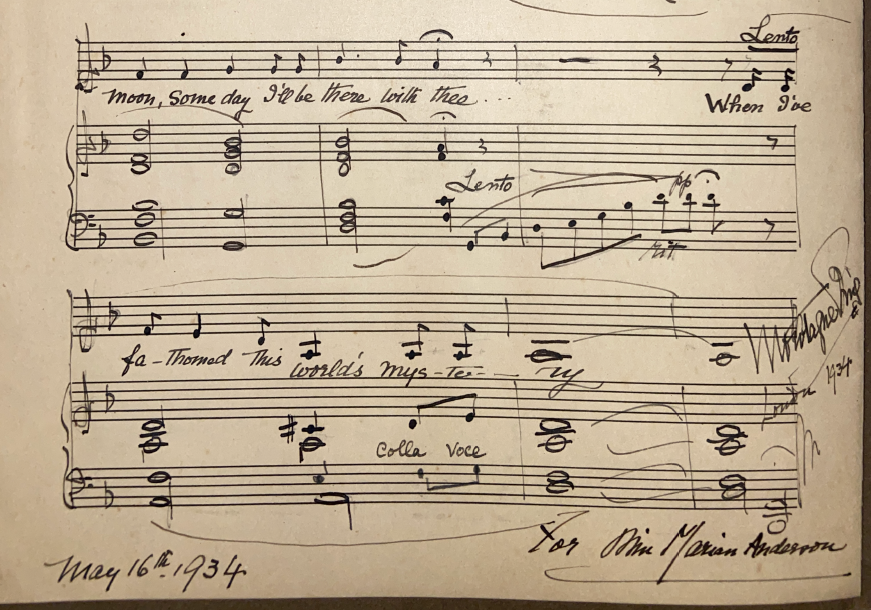

Aldridge stopped publishing her music around 1930. However, she composed two last songs with Anderson’s contralto voice in mind: “Shine, Pale Moon” and “Pent.” For whatever reason, she signed “Shine, Pale Moon” as Montague Ring, and “Pent” as Amanda Ira Aldridge. Both songs appear to date from around 1934 and remain unpublished, with manuscript scores preserved as part of the Marian Anderson papers at the University of Pennsylvania, as well as in the Schomburg Centre for Research in Black Culture in New York. The copies held in Pennsylvania have been made available online by Stephen Rodgers as part of the website Art Song Augmented. These songs have now been recorded for the first time by tenor Brian Smith Walters and pianist Adam Johnson.

“Shine, Pale Moon” and “Pent” mark a distinct departure from Aldridge’s earlier output of drawing-room or parlour music towards a more serious and emotionally mature style of English art song. So far, I have been unable to trace any details pertaining to Betty Haddon, the lyricist of “Shine, Pale Moon”, but she could be the daughter of British drama critic Archibald Haddon, who knew Aldridge and wrote a favourable piece commemorating her Father which appeared in The Era before being reprinted in W.E.B. Du Bois’s journal The Crisis.

1. O pale Moon, so far above / Shining down on those I love,

Over the wide world you rose. / Viewing your reflections in the streams

Sending to the sad forgetful dreams.

2. O moon, will you shine, I pray / on a land so far away

In the house where once I lay! / And Moon, will you kiss his silken hair,

And give him sleep, if he’s sleepless there?

3. O pale Moon, until I die / I will see these in the sky

A friend, when friendless am I / And moon, someday I’ll be there with thee

When I’ve fathomed this world’s mystery.

The lyrics of “Pent” derive from Harlem Renaissance poet Georgia Douglas Johnson’s first book of poetry The Heart of a Woman (1918), the title poem of which has become well known through Florence Price’s later setting. The condensed intensity of “Pent” begins peacefully and simply before building towards the climactic phrase “Break! Break! Ye floodgates of my heart / all pent in agony.” The poem may have resonated with the composer during what must have been one of the most challenging periods of her life: the suicide in 1932 of her beloved older sister, Luranah, whose own promising international career as an operatic contralto had been sadly cut short when she developed rheumatism in her thirties.

1. The rain is falling steadily / Upon the thirsty earth,

While dry-eyed, I remain, and calm / Amid my own heart’s dearth.

2. Break! break! ye flood-gates of my tears / All pent in agony,

Rain, rain! upon my scorching soul / And flood it as the sea!

Amanda never married and devoted much of her life to caring for her sister at their family home 2 Bedford Gardens in Kensington, three blocks from Kensington Palace. Following her sister’s death, she continued to support herself by working as a vocal coach throughout the Second World War and well into her eighties.

In May 1950, Anderson – now at the height of her celebrity – appeared again in London to perform a recital at the Royal Albert Hall. Hearing the news of Anderson’s visit, Aldridge wrote to her loyal friend and long-term correspondent in America, Lawrence Brown, that “I would like [Marian Anderson] to sing my song ‘Pent’ – I think I will post it to her at the Hall where she gives her recital. Perhaps you remember the song (in manuscript) the words are by an American woman poet.”

Whether or not Aldridge sent a copy of “Pent” directly to Anderson in London is not known. However, she evidently sent her manuscripts to Brown, who forwarded a copy to Anderson shortly before Aldridge’s death in 1956. It seems that Anderson did not programme Aldridge’s songs in her major recitals, however she did incorporate English art songs by the likes of Roger Quilter, Cyril Scott, Peter Warlock and Benjamin Britten. Aldridge’s compositions, while modest in scale, belong to this early-20th-century flourishing of British song. At the same time, they reflect her significance within a tradition of Black classical music-making and transatlantic cultural exchange at the heart of Empire.

Notes

The banner photo is of Amanda Ira Aldridge, from AME Church Review (Oct. 1912), 118.

For previous WSF posts on Marian Anderson, see these by Mark Burford, Carol Oja, and Stephen Rodgers, who is joined by Carol Oja and Mark Burford.

For a recent post that explores Amanda Ira Aldridge’s adoption of the name Montague Ring, see this one about women who assumed male pseudonyms.

Marian Anderson, My Lord, What a Morning, An Autobiography (New York: Viking, 1956).

Letter from Marian Anderson to Amanda Aldridge, 4 January 1929. Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections, Northwestern University.

Letter from Amanda Aldridge to Lawrence Brown, 19 February 1950. Schomburg Centre for Research in Black Culture.