A century ago, in the decades when far more women composed and published songs than ever before, many ambitious men songwriters found it advantageous to adopt women’s names for some of their publications. Some sought to gain a commercial advantage by targeting a female audience; some evidently wanted cover to express thoughts then considered feminine; and a few prolific men, who wrote far more songs than one composer could successfully market, chose a variety of pseudonyms, including women’s names. In a separate class were the song sharks, musical men employed by publishers who preyed on amateur poets who hoped to strike it rich with a song hit.

Yet for every man posing as a woman, there were several women who made careers by resorting to one of two gender-obscuring strategies: choosing a man’s name or replacing their first names with initials. Some women attached themselves to one pseudonym for their entire compositional careers. In this they followed the examples of 19th-century women writers. Amandine Aurore Lucile Dupin de Francueil always retained the name George Sand, and in England, Mary Ann Evans was always George Eliot. Several prominent men showed a similar fidelity to their authorial persona: Eric Arthur Blair forever published as George Orwell, and Charles Lutwidge Dodgson as Lewis Carroll.

A few women veiled themselves with male identities that projected an image more exotic than their given names. Emilie Frances Bauer became Francisco di Nogero, creating a nom-de-plume by reversing the spelling of her home state, “Oregon.” This name evidently lent credibility to five Spanish-themed songs of hers, such as “El Arriero” (aka, “My Love Is a Muleteer”). She was the older sister of eminent composer and music critic, Marion Bauer. Among others there are Rosaliene Travis as Lawrence Zenda (USA), Jane Jackson Roeckel as Jules de Sivrai (UK), Maud Wingate as Carlyon de Lyle (UK), and folksong collector Lucy Broadwood as J. B. de la Borde (UK).

Stanley Dickson, et al

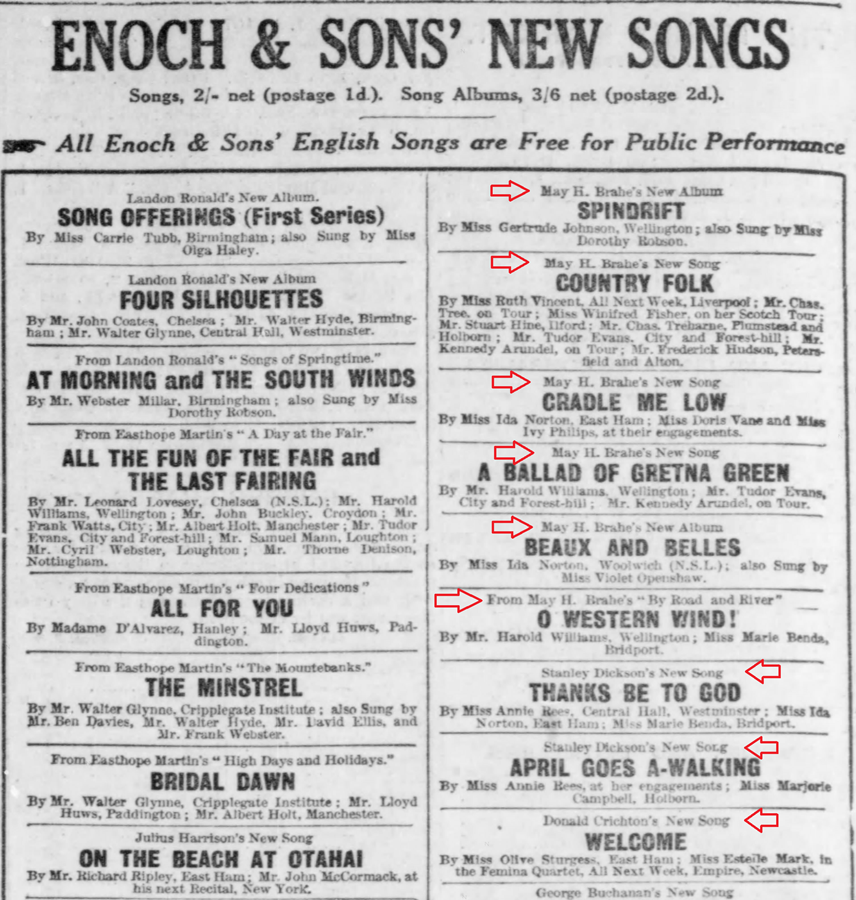

Of all the women who chose to publish under other names, only one, Australian May Brahe, can be compared to men like Robert Keiser/King and J. S. Zámecnik, who had multiple pen names as a strategy for maximizing the number of songs they could sell. Over the decades she lived in London, Brahe resorted to seven different pseudonyms for 28 of her 168 songs. Between 1916 and 1934 she became Stanley Dickson for 13 songs, Donald Crichton (for 8), Henry Lovell (2), George Pointer (2), Mervyn Banks (1), Alison Dodd (1), and Stanton Douglas (1), publishing primarily with Enoch & Sons. In 1916 six songs appeared under her own name, and one each by Mervyn Banks, Donald Crichton, and Stanley Dickson.

An ad for Enoch & Sons’ latest offerings in fall 1921 demonstrates the merits of Brahe’s “noms-de-guerre” (as they were sometimes called). Brahe has six titles advertised, which represents thirteen songs since “Spindrift” was a set of five, and “Beaux and Belles” a cycle of four. Beneath these come three of her songs attributed to Stanley Dickson and Donald Crichton.

This ad announces, inauspiciously, one of Brahe’s greatest successes, the sacred song “Thanks Be to God.” She credited it to Stanley Dickson, not coincidentally, the name of her brother (Sydney Morning Herald, 3 Dec. 1919). Through various publishers Brahe soon issued it in multiple arrangements, including duos, trios, and quartets. A century later, choirs around the world still perform it in various arrangements and translations, including in Seoul by the Saeronam International Church Choir singing in Korean, in The Netherlands by The Credo Singers of Rotterdam, in Uruguay as “Gracias a Dios”, and in Brasilia as “Graças a Deus” by the choir of the Igreja Memorial Batista de Brasília.

Successful women songwriters who chose one male name and stuck with it for many years are eventually unmasked. Sooner or later, as with J. K. Rowling writing as Robert Galbraith, the ruse is detected. From that point on, do we read – or hear – a woman writing/composing as a man? Or is the feigned gender identity irrelevant to our perceptions of style and meaning? The three most prominent examples of such women songwriters are all British, but unusually so: two were culturally mixed (French, English, Irish; and Polish, Belgian, English), and one was racially and culturally mixed (Black American, Swedish).

Guy d’Hardelot

One of the most successful British-French songwriters, Helen Guy, devised a pen name that drew entirely on her heritage. Born in 1858 to an English father and French mother in the Château d’Hardelot, near Boulogne-sur-Mer, she published her first compositions in 1889 as Guy d’Hardelot. She never relinquished this professional name, even after marrying William T. Rhodes two years later (Rhodes clearly didn’t expect her to take his name professionally; as a poet, he signed his work Raymond St. Leonards).

Both Jules Massenet and Charles Gounod encouraged her compositional efforts. Gounod evidently enjoyed addressing her as “Monsieur Guy d’Hardelot,” yet once she settled in London in the mid-1890s, the London press frequently referred to her as “Mme. Guy d’Hardelot.” More distant admirers nevertheless continued to assume she was a man. At the height of her fame, she lamented the hundreds of letters she received addressed to “Guy d’Hardelot, Esq.” (Baltimore Sun, 20 June 1909).

Stylistically, d’Hardelot often favored massive block chords, and bombastic operatic conclusions that became known as “d’Hardelot endings” (New York Times, 8 Jan. 1936). One critic heard in her music “the emotional style” of Gabriel Fauré (London Era, 10 Nov. 1898). Her most frequently performed song, the wedding warhorse “Because” has long struck me as epitomizing a British imperial confidence that was at its peak when the song appeared in 1902, the same year that Elgar published “Land of Hope and Glory” (aka “Pomp and Circumstance”). As a wedding song “Because” expresses a paternalistic view of love as ownership: “Because God made thee mine / I’ll cherish thee through light and darkness all the time.”

But she was also capable of lighter, gentler voices, as in “Three Green Bonnets” or “I Know a Lovely Garden.” Neither has a d’Hardelot conclusion, nor does “My Message,” in which a secret admirer sends flowers, anonymously: “I sent you red roses, and I know / My heart went with them when I saw them go, / They carried in their petals love for you, / And yet who sent the flow’rs, you never knew!” Nan Merriman beautifully rendered d’Hardelot’s inspired elision between the final words (you never knew) and the repeat of the first (I sent you red roses).

Montague Ring

Amanda Ira Aldridge (1866–1956) was the British namesake of her parents: a famous Black-American-Shakespearean-actor father, Ira Frederick Aldridge, and a Swedish-singer mother, Amanda Brandt; she was the younger sister of Luranah Aldridge, an acclaimed opera singer at Covent Garden and in the United States. Amanda Ira Aldridge assumed the name Montague Ring as the composer of numerous popular piano pieces, dances, and light instrumental works, as well as 31 songs.

Even though she never married, and thus never took a man’s name in that traditional sense, her name evolved. While studying at the Royal College of Music she was both “Amanda Aldridge” and “Miss A. Ira Aldridge.” But then in her years as a singer, “Amanda” fell away. She was known in the British press either as “Miss Ira Aldridge” or “Miss A. Ira Aldridge.” Perhaps her preference for “Ira” stems not just from an identification with her father; she also had two brothers named Ira. Her decision to select and retain a male pseudonym may therefore have had personal motivations not shared by other women composers.

Aldridge reportedly once said that she “adopted the name of ‘Montague Ring’ in order to keep her work as a composer apart from that of a singer and instructor” (Cuney Hare, 316). Indeed, the divide between her two musical worlds was pronounced. As a singer she performed works of Mozart, Schubert, Brahms, Dvořák, and Samuel Coleridge Taylor, as well as some of the more popular middlebrow composers of the day, singing in many different languages, including Danish. As a teacher, she doubtless benefited from being known as “the last surviving pupil of Jenny Lind” (Birmingham Daily Gazette, 17 April 1954). Black American singers who she taught include Marian Anderson, Roland Hayes, and Paul Robeson (Cuney Hare, 318).

The composer Montague Ring plowed different turf. The name emerged in 1907 when she published a piece for piano and several songs including “My Dreamy, Creamy Colored Girl,” and “When the Colored Lady Saunters Down the Street,” for both of which she also wrote the words. A year later she published “My Little Corncrake C**n.” Her worlds as a performer and teacher spoke different languages. Here is her song “Little Missie Cakewalk,” with a line about “a regular dusky Queen.”

At least in London, where the press often referred to the compositions of “Mr. Montague Ring,” she was too well known for her pseudonym to go unrecognized. An account of one concert in the London Daily Telegraph (12 July 1909) praises Ira Aldridge for her work as a singer and pianist, and Montague Ring as a composer.

Poldowski

Like Aldridge, Irène Régine Wieniawski had an illustrious father. She was born in Belgium in 1879 to the great Polish violin virtuoso, Henryk Wieniawski, and his British wife Isabella “Bessie” Hampton. Having grown up in Bruxelles, she moved with her mother to London, where she met her husband, Sir Aubrey Edward Henry Dean Paul, 5th Baronet of Rodborough. Lady Dean Paul published her first works as Irène Wieniawski. After marrying, and evidently after the death of her first child, a two-year-old son, she left England to study composition in Paris. Only in 1908 did she begin to appear as a theatrical composer with the single name Poldowski. She retained the name until her death in 1932.

While she was widely known during her performing career as “Mdme. Poldowski,” an early announcement in The Observer assumes her to be a man: “Special music has been composed by M. Poldowski and a special scene designed by Mr. Charles Rickerts for ‘Lanval,’ the original poetic drama by Mr. T. E. Ellis (a nom de théâtre, it seems, of Lord Howard de Walden)” (10 May 1908). Years later a reporter near Manchester, England, asked her why she had chosen this name: “Well, I am the daughter of Wieniawski, the violinist, who was one of the greatest violinists of his day, and I also had an uncle and cousin who were wonderful musicians, so I thought I ought to change my name. I thought it wiser to take a man’s name as everything would be against me as a woman” (Bolton News, 29 June 1927). She was perhaps influenced by the fact that he was widely called by his last name only, Wieniawski.

Among her extraordinary songs is Berceuse d’Armorique on a poem by Anatole Le Braz, one of three songs that she wrote after the death of her first child, her two-year-old son Aubrey. Among the passages that stand out is her setting of the two lines “Au pays du Froid, la houle des fiords / Chante sa berceuse en berçant les morts” (In that cold country, the swell of the fjords / Sings its lullaby while lulling the dead). A text and Hélène Lindqvist’s translation are available.

A common denominator?

Among the women who elected to publish songs with pseudonyms a century and more ago, these four stand out for the degree of their success. May Brahe differs from the other three because she primarily issued her songs with her given name. She likely resorted to pen names not from her own volition but at the urging of her publishers.

In contrast, the other three women each chose a professional persona – becoming Guy d’Hardelot, Montague Ring, and Poldowski – at or near the beginning of their careers as composers. Could similarities in their immediate family backgrounds have contributed to their decisions to assume a new identity? They had each grown up with emigrant parents from different countries: Aldridge’s parents from the U.S. and Sweden to England; Wieniawski’s from Poland and England to Belgium; Guy’s British father to France. And Wieniawski and Guy had both moved from the continent to London as young adults. Two of the most successful men who published as women had similar family histories. The father of Robert Adolph Keiser / Robert A. King had emigrated to the U.S. from Bavaria, his mother from Prussia, and J. S. Zámecnik’s parents were both from Southern Bohemia (now the Czech Republic). As Learned Hand once said of Samuel Goldwyn, “A self-made man may prefer a self-made name” (Pilkington). Even, possibly, a new gender.

As we will see in Part 2 of this post, the women who chose instead to obscure their gender behind their initials fit a very different profile.

Notes

Montague Ring’s song “Azalea” is presented on Art Song Augmented.

Salome Thomas Cade (USA) became Clayton Thomas, and Isabel Varney Monk (AUS) published four of her 37 songs as Varney Desmond.

On Guy d’Hardelot, see Theodore Baker, ed., A Biographical Dictionary of Musicians (New York: G. Schirmer, 1900), 250-51; and William Francis Collins, Laurel Winners: Portraits and Silhouettes of Modern Composers (Cincinnati: Church Co., 1900), 97-98.

Maude Cuney Hare, Negro Musicians and Their Music (Washington, DC: Associated Publishers, 1936).

Catherine A. Judd, “Male Pseudonyms and Female Authority in Victorian England,” Literature in the Marketplace: Nineteenth-Century British Publishing & Reading Practices, ed. John O. Jordan and Robert L. Patten (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003).

John Pilkington, “Pseudonyms: Behind the Author’s Mask” RLF News (9 Oct. 2017).