I spend a lot of time digging for new song repertoire to study. In fact, it’s become something of an obsession. I trawl through various online databases of digitized musical manuscripts or out-of-print scores; I hear about a song composer I didn’t previously know and then launch into a furious quest for everything I can get my hands on.

Why I allow myself to travel these circuitous routes is something of a mystery to me. Partly it’s a belief that our view of music history and our understanding of musical style will only ever be incomplete if we stick with what we already know. To some degree it’s a desire to enrich my teaching and scholarship with voices that have been neglected and forgotten. It’s also just restlessness – a craving for the endorphin rush that comes with discovering something new, a love of the next treasure hunt.

One treasure that particularly obsessed me over the past few years was the songs of Marie Franz, née Hinrichs. She published only one opus of songs in 1846, when she was eighteen. That same year she got engaged to the composer Robert Franz and from then on wrote no more music. Or so I thought, until I discovered a manuscript booklet of fifteen songs in the collection of the Händel-Haus in Halle, Germany, which I subsequently prepared in a modern edition. Marie Franz’s songs captivated me so much that I wrote three essays on them (one in the Women’s Song Forum), started using them in my classes, recommended them to singers and pianists, and generally talked about them with everyone I could, wanting others to become super-fans like me. (My poor parents, neither of whom is a professional musician, had to suffer through my disquisitions on Franz’s otherworldly harmonic language.) Some people responded enthusiastically. Often, though, the response was more muted than I had hoped. How, I wondered, could they not see the rare talent of this composer? Why were they also not swooning at her chord progressions?

The problem, I came to realize, is that they didn’t have the chance to really hear Marie Franz’s songs. They could read about them in my essays or even listen to me sing and play them imperfectly (the songs, that is, that didn’t stretch my amateur pianistic skills too far), but they couldn’t experience them fully without hearing them performed beautifully.

Art Song Augmented

That realization led to the creation of Art Song Augmented, a website devoted to songs by composers whose music has been marginalized. The site includes high-quality video recordings, commentary, scores, and other resources for those interested in learning more about this repertoire. My goal was to provide a forum for those who, like me, were hungry for new music and new voices in the world of art song but might not know where to start. Another goal was to create a community committed to celebrating this extraordinary and understudied body of music.

I launched Art Song Augmented in March 2022, after working for several months with the amazing Anastasia Witts, of Artist Digital, who designed a beautiful, inviting, and user-friendly site. (Anastasia also designed Women’s Song Forum.) Marie Franz was one of four composers that I featured when the site first went live. The others were also little-known German composers whose songs had never been recorded: Marie Vespermann, Mary Wurm, and Clara Faisst. With the support of funds from an endowed professorship, I hired pianist Chanda Vanderhart, soprano Rebecca Nelsen, and baritone Klemens Sander to record a few songs by each composer.

The site now has pages on 31 composers from ten countries. All of the composers come from marginalized groups, and there’s a special emphasis on women composers and composers of color. One such composer, whom I didn’t know until my colleague Camille Ortiz brought him to my attention, is the Pervian composer Theodoro Valcárcel (1900–42). Here is Ortiz’s recording of Valcárcel’s Tahwa inka’j tak’y-nam (Cuatro canciones inkaicas, Four Inca Songs), with lyrics in Quechua, an indigenous language spoken by the Quechua people of the Peruvian Andes.

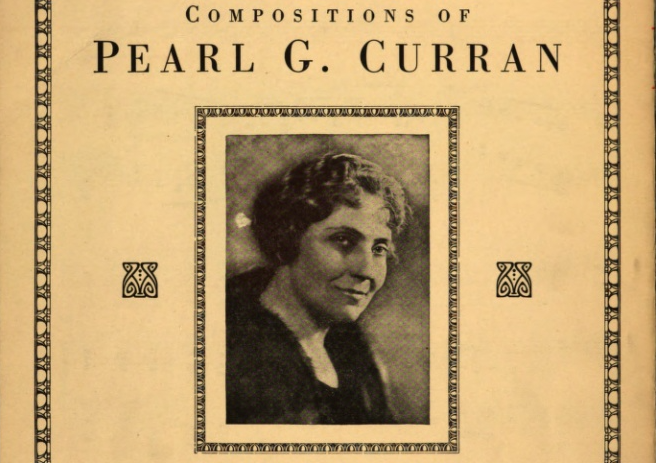

Valcárcel’s songs were published in 1930, but the repertoire on the site extends well before and after the 20th century, spanning from the early 1800s to the present day. The earliest song is a piece from 1838 by Josephine Lang, and the latest is by Sarah Kirkland Snider from 2023. And of the 84 video recordings on the site, 35 are world-premiere recordings that I commissioned from performers all across the globe. One of the greatest joys of creating the site and seeing it grow has been connecting with these performers, as well as with composers, students, lay listeners, and a host of people from different fields and different backgrounds, who are united by their desire to unearth song repertoire that has been hidden for far too long.

Jocelyn Freeman, a pianist and conductor who founded SongEasel, an arts and education charity operating in South East London, has been an especially delightful collaborator. She has recorded six world premieres for Art Song Augmented, the most recent being two songs by Elise Schmezer (ca. 1810?–1856?). Schmezer published about 40 songs between 1848 and 1856, but little is known about her life, except that she established herself as a musician in Braunschweig, in north central Germany (we know this only because several composers from the city dedicated works to her, describing her as “the pianist Elise Schmezer”). After the mid-1850s, however, she vanishes without a trace.

The main evidence we have of her musical activities, therefore, consists entirely of her glorious songs. They show a masterful approach to harmony and a natural sense of drama, as you can hear in “Die Sultanin,” a song about a female sultan who mourns her departed beloved while ravens caw and sycamore trees rustle.

I started by talking about my obsession with digging for new music – which puts me in mind of Seamus Heaney’s famous poem of that title. The poem begins with a description of his father digging with a spade, planting potatoes, just as his father did. Heaney has “no spade to follow men like them,” but he does have a pen, tucked between finger and thumb. “I’ll dig with it,” he says in the final line. A pen; a singing voice; a piano played by someone seeking new scores and sensitive enough to bring them to life; an article or blog post about underexplored repertoire; a website devoted to songs that deserve to be heard: we can dig with these.

I’m still digging, but now I have a network of fellow diggers – and a sturdy digital spade to work with.