J. K. Rowling, Dan Brown, Mary Ann Evans and Louisa May Alcott have one authorial trick in common: they are among many writers who have assumed a fictitious identity in order to switch genders, in their cases becoming, respectively, Robert Galbraith, Danielle Brown, George Eliot, and A. M. Barnard. The reasons authors have for this strategic literary subterfuge vary. Some have perceived a commercial advantage to writing as a man or woman and targeting a male or female audience; others sought anonymity, either to avoid censorship, or to avoid unwanted associations with their primary identity, or because they wanted cover to express thoughts society deemed feminine or masculine. For writers this practice became common in the 19th century and has continued to the present day.

Not so for songwriters, male and female. Gender shifts began later and then disappeared, undermined in part by the rise in the mid-20th century of singer-songwriters who performed their own material. Live performances on television for all to witness rendered this subterfuge impossible. Men began to publish as women by the 1850s, when Septimus Winner issued “Listen to the Mocking Bird” (1855) as Alice Hawthorne. When large numbers of women became productive songwriters, especially from the 1890s into the 1930s, some recognized the potential benefit to publishing as a man. Amanda Aldridge, a Black woman composer in Edwardian England, stood a much better chance of success as Montague Ring.

In this post I discuss four men who profited from assuming a woman’s name; Part 2 will then take up the many women who published as men. Here are five successful popular songs published between 1913 and 1925, five songs by four men writing in a sentimental style to express thoughts they considered more appropriate for women.

Men had ample evidence of the thriving market for women’s songs. From 1890 to 1930, according to the latest figures in my database, more than 5300 women in the U.S and British Empire published nearly 23,000 songs. Of these women, forty were responsible for at least 75 songs, and fifteen for between 135 and 369. This post is a felicitous by-product of my database, the result of my ongoing struggle to weed out names that do not belong, not just men posing as women, but also men with non-gendered names like Leslie and Vivian, and in England even Beverly, Joscelyn, and Laurie.

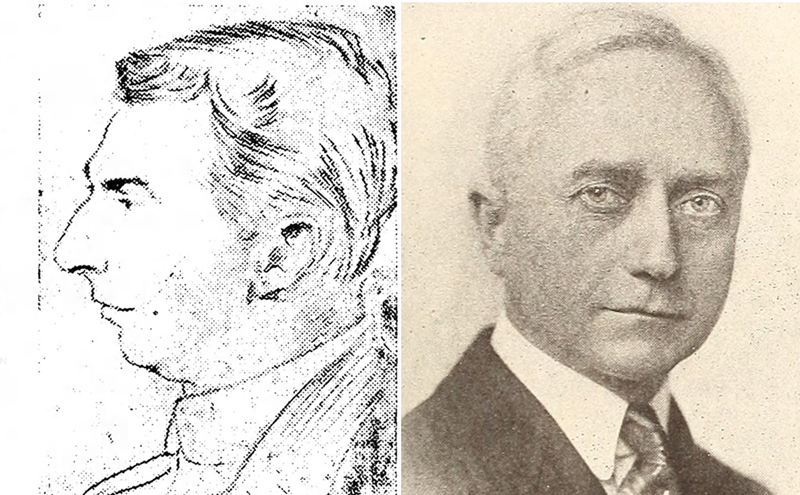

It is no coincidence that the central decades of women as songwriters were also the peak years of men adopting women’s names. The four composers highlighted here are John Neat (1876–1949) from London; J. S. Zámecnik (1872–1953) from Cleveland and Los Angeles; Robert Adolph Keiser / Robert A. King (1862–1932) from New York; and Kennedy Russell (1883–1954) from London.

John Neat published some 54 songs as Lilian Ray, including what quickly became his greatest hit, “The Sunshine of Your Smile” (1913). Reaching #1 in 1916, it also appeared that year in France as “Ton doux sourire.” Over the next century it has been sung and recorded by a wide range of popular and operatic singers and jazz musicians: John McCormack, Tito Schipa, Django Reinhardt and Stephane Grappelli, Frank Sinatra, Gordon Macrae, James Melton, and Stuart Burrows. A remake of the song was a hit for Mike Berry in 1980. After the enormous success of “The Sunshine of Your Smile,” he followed with several spin-offs, including “The Shadow in Your Eyes” (1916) and “The Sunshine of Love” (1916). Incredibly, in the euphoric post-war year of 1919, he issued fifteen songs in her name and nine in his own.

Once he began to publish as Lilian Ray, the songs that Neat published as himself projected a distinctly masculine profile: “Remember Louvain. March” (1914), “England’s Contemptible Little Army” (1915), “They Are Coming, Mother Country” (1916), “We Are Marching on to Victory” (1916), and “On the Road to Armenteers” [sic]. Neat’s alter-ego Lilian Ray gave him a voice for poems he felt spoke to women, but it also allowed him to more than double his out-put without overwhelming his market.

J. S. Zámecnik was a prolific songwriter, a conductor, and, from the early years of silent films into the 1940s, a film music composer. He possibly composed 2000 compositions. Born and raised in Cleveland, he spent the year 1896–97 studying with Antonín Dvořák at the Prague Conservatory of Music. After returning home he served for three years as a second violinist in the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra under Victor Herbert. Over the next two decades he composed many songs and silent film scores for Sam Fox & Co. in Cleveland. After relocating to Hollywood in 1924, he wrote scores for films for the rest of his career.

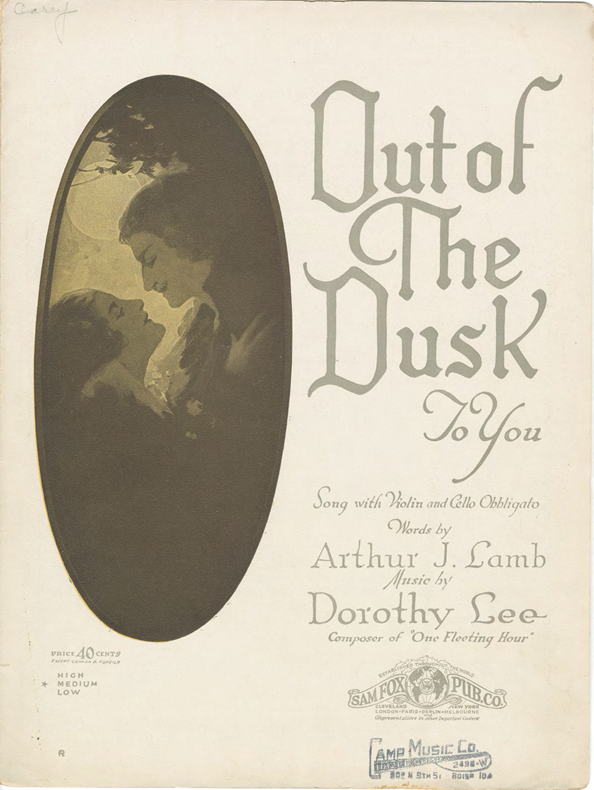

Almost single-handedly, Zámecnik made Sam Fox & Co. appear to be a thriving business with a deep stable of composers. He resorted to at least 14 pseudonyms, many of them male: Lionel Baxter, Robert Creighton, Arturo de Castro, “Josh and Ted”, J. Edgar Lowell, Jules Reynard (for floral pieces), Hal Vinton, and Grant Wellesley. But his multiple female identities included several that sound like the aristocratic names Hollywood studios assigned their leading actresses: Jane Hathaway, Kathryn Hawthorne, Roberta Hudson, and Dorothy Lee. For the Hawaiian song “Aloha Sunset Land” he became Ioane Kawelo.

His songs credited to Dorothy Lee were among his most popular, recorded and arranged for many years. “Out of the Dusk to You” (1922) could be had in versions with obligato violin and cello, for mixed choir or as a duet, and in instrumental arrangements. “One Fleeting Hour” (1915) eclipsed them all. A search in Newspapers.com, which includes newspapers in the United Kingdom, Canada and Australia, on “One Fleeting Hour” and “Lee” between the years of 1915 and 1950 identifies over 10,000 citations. One enthusiastic plug for the song in Melbourne gushed, “This song is not the hit of a passing moment, but rather the Song Success of all time” (The Age, 10 May 1919).

As Jane Hathaway, Zámecnik composed “I’m a-Longin’ fo’ You” (1914), setting a dialect poem by Karl Fuhrmann that was interpreted variously as Black American and as Irish. It was clearly indebted to Frank Stanton’s poem “Just a-Wearyin’ for You,” in the version made famous by Carrie Jacobs Bond’s 1901 setting. Elsie Baker recorded it in 1916, Sophie Braslau and Merle Alcock each in 1919. Here is Australian contralto Clara Serena’s moving version from 1929.

The prolific songwriter Robert Adolph Keiser also published as Robert A. King, especially after 1917. But he also assumed other names: Betty Chapin, Mary Earl, Kathleen A. Roberts, Alice Write, and possibly as many as 40 or 50 others. Beginning in 1918, he contracted with Shapiro-Bernstein Music Publishers to supply four songs each month, a rate of productivity that profited from multiple identities. Three hits attributed to Mary Earl were “My Sweetheart Is Somewhere in France,” “Dreamy Alabama” and “Beautiful Ohio.” The song “Sweethearts” (1918), attributed to Alice Write, began “You were just eight and I was just ten.” With its artfully drawn cover of a boy and girl, it told a story of childhood love that evidently required a female songwriter. Under his own name he composed witty double-entendre songs such as “I Scream, You Scream, We All Scream for Ice Cream.” Together with Lew Brown and Ray Henderson he wrote “Why Did I Kiss That Girl?” (1924) and “Ain’t My Baby Grand?” (1925).

But the biggest money-maker of his career was the ballad that became the state song of Ohio, “Beautiful Ohio” (1918) by “Mary Earl” with lyrics by Ballard Macdonald. It quickly became a #1 hit and was recorded by dozens over the next century, including Henry Burr, Fritz Kreisler, Glenn Miller, Connie Francis, and three country singers, Kenny Roberts, Chet Atkins, and Marty Robbins.

Like J. S. Zámecnik, the British songwriter Kennedy Russell was a film composer with many scores to his credit between 1935–52. He published several songs as Barbara Melville Hope, a name that still creeps into recitals of songs by women. Between 1920 and 1935 Boosey & Co. issued 14 songs in “her” name, the most enduring of which is “Through All the Days to Be” (1925). The poem is by Royden Barrie, a pseudonym for Rodney Bennett, the father of Richard Rodney Bennett.

I see no obvious explanation for why Russell chose to employ a female pseudonym. The domestic character of some of the songs he published with his own name – songs such as “Let Me Sit in Your Garden” (1926) and “When the Children Say Their Prayers” (1935) – could easily have suggested settings by a woman; and yes, he was a prolific songwriter, but nowhere close to the manic output of King/Keiser or Zámecnik. And unlike Zámecnik, Robert Charles Kennedy Russell had no need to create a culturally mainstream cover-name. He already had several.

Finally, in addition to musically gifted and successful men posing as women, there was a predatory group of songwriters, a group of interest today perhaps only as a sign of how eager many amateur poets were to have a song published. A century ago the phenomenon of song mills – swindlers who advertised for people to send in poems that would be “professionally” set, offering the unrealistic hope that they could become wealthy in the process – enticed thousands of gullible people each year. In Washington, D.C., there was the H. Kirkus Dugdale Publishing Company. They advertised nationally, making extravagant promises:

$10,000 FOR A SONG RECENTLY PAID. Send me Your Song Poems for exam, and offer. H. Kirkus Dugdale, Dept. 12, Washington, D. C. (Philadelphia Inquirer, 19 June 1910).

Among the songs printed by Dugdale were several attributed to women, especially Genevieve Scott, Vivian Brooks, and Jean Buckley. In 1913 “Jean Buckley” alone was responsible for 180 copyrighted songs. Late that year the owners of Dugdale were arrested and tried for mail fraud (Washington Times, 27 Sept. and 16 Dec. 1913). But they, and song mills in Chicago and New York City, continued to churn. Most, but not all, of such “song sharks” were men.

The four men featured in this post were exceptional in the numbers of songs they published as women and in the popularity of those songs (ten other men are listed in the notes). Yet, unlike several women – such as Salome Thomas Cade (aka, Clayton Thomas) – who stayed with one male pseudonym throughout their careers, no man published entirely as a woman. For men it was a diversion, an option. Moreover, the numbers of women who assumed male pseudonyms was greater. Women had more to gain from masquerading as men.

One unintended consequence of men composing best-selling songs by posing as women is easily overlooked: most people, including aspiring songwriters, would have had no idea that these successful composers were NOT women. The likes of Jane Hathaway, Lilian Ray, and Barbara Melville Hope augmented the impact of prominent women composers active in these years, enhancing the impression that songwriting was a career in which women could flourish. The greatest contribution of Alice Hawthorne and his successors was arguably this inspirational delusion, one that helped stoke the ambitions of musical women.

(To be continued.)

Notes

The banner photo is a sketch of John Neat from the Hull Daily Mail (21 July 1915) and a photo of J. S. Zámecnik from The Musical Observer 26/12 (Dec. 1927): 37.

Other men posing as women include: Alfred Rawlings (UK) as Florence Fare, Edith Fortescue, Gladys Melrose, Constance V. White and nearly 20 others; Charles Arthur Rawlings (UK) as Jeanne Bartelet and Nita; Lawrence Wright (UK) as Kathleen Cavanagh, Betsy O’Hagen, Lilian Shirley, and several men; Oscar Ernst von Ernsthausen (UK) as Muriel Mardelotte; Richard G. Grady (USA) as Bessie Barrett; Robert C. Haring (USA) as Jeanné Gravelle; Earl Haubrich (USA) as Melba Wirth; Will Rossiter (USA) as Kathryne E. Thompson; James Royce Shannon (USA) as Jayne Sterling (“Dear Little Mother o’ Mine”); and Harold Vicars (UK/USA) as Moya.

Zámecnik’s application for a passport to go to Europe for a year was approved on 18 Aug. 1896. That application is in the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA); Washington D.C.; NARA Series: Passport Applications, 1795-1905; Roll #: 475; Volume #: Roll 475 – 1 Aug. 1896 – 31 Aug. 1896. Accessed on Ancestry.com. For more on his too-little-studied career, see this and this.

Kennedy Russell’s pseudonym is revealed in Catalog of Copyright Entries 1951 Renewal Registrations-Music Jan-Dec from 1949-1953 and in other copyright renewal records. Information on Jean Buckley’s publications is from the Catalogue of Copyright Entries, Part 3: Musical Compositions new series, vol. 8/11-13 (Washington, D. C.: Government Printing Office, 1913).

For more on Dugdale, see this post.

On the gendered pseudonyms of writers, see the recent dissertation of Heather Anne Hannah, Male Use of a Female Pseudonym in Nineteenth-Century British and American Literature (Ph.D. diss.: Murdoch University, 2018).

A valuable resource for composers and their pseudonyms is Jeanette Marie Drone, Musical AKAs: Assumed Names and Sobriquets of Composers, Songwriters, Librettists, Lyricists, Hymnists, and Writers on Music (Lanham, MD: The Scarecrow Press, 2007).