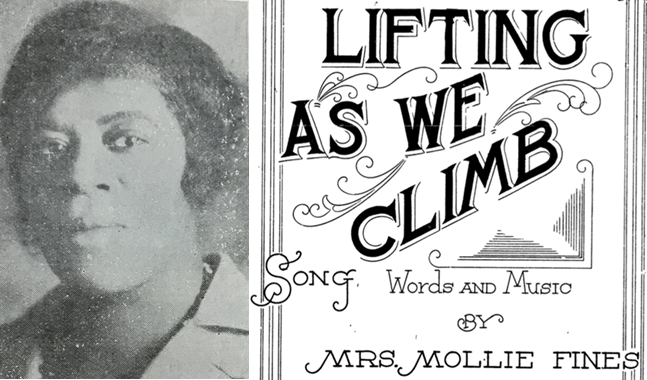

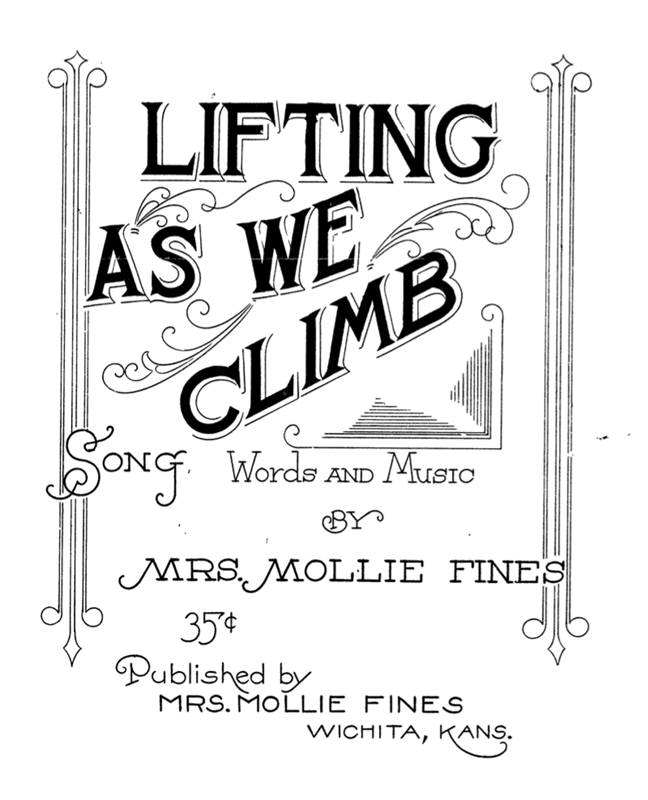

At their meeting in Oakland, California, in 1926, the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs (NACWC) adopted the song, “Lifting as We Climb.” Composed by Mollie Fines of Wichita, Kansas, the song was named for the group’s motto, which underscored the goal of racial uplift for African American women.

Let us hold our banner high

Forward marching all the while

And we’ll win the world for good.

Lifting as we climb is the national command,

To educate and graduate all over the land.

Fines taught her song to the conference attendees and gave the Association the profits from sales of 300 copies she had self-published. Fines’s personal initiative and sense of mission had led to her selection as the NACWC’s national music director by its president, Mary McLeod Bethune. She served from approximately 1925 to 1929.

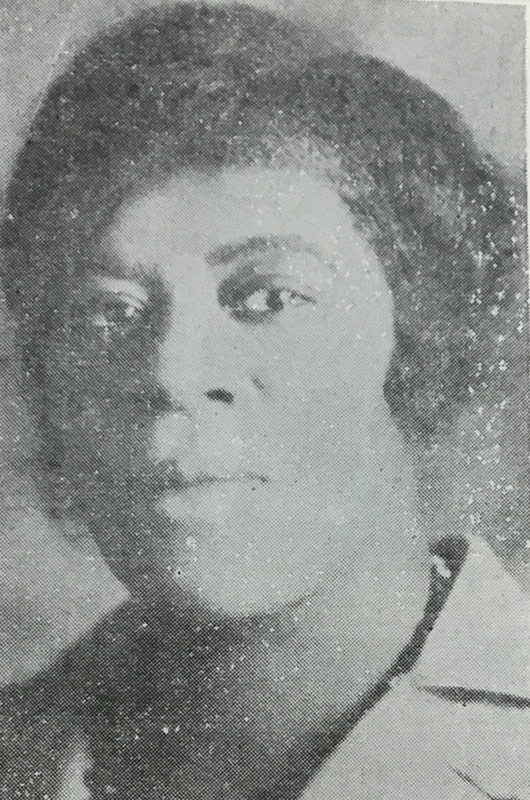

When I began researching Fines for my forthcoming book on clubwomen activists, I found over 400 mentions of her in The Negro Star, the newspaper for Wichita’s 6000 African American residents in the 1920s. Active in civic life, Fines sang at local churches and was a frequent soloist for funerals. She was a member of multiple clubs, also attending meetings of the Wichita City Federation and the Kansas Association of Women’s Clubs. Fines was in charge of the choir at St. Paul A.M.E. Church for many years. She promoted the music of Black composers and organized contests that influenced African American music making in Kansas. Fines was often at the helm of events organized in support of the Black community: concerts, pageants, or fashion shows that raised money for women’s groups’ charitable activities.

Typical for earlier newspapers, The Negro Star sometimes mentioned Mollie Fines’s street addresses, so I searched for them using Google Earth. After 1929, Fines and her husband Thomas lived on Cleveland Street. The site of their house is now an empty lot, but during the couple’s years there, shops, an elementary school, and a movie theater were situated in their middle-class neighborhood. When I looked for Fines’s earlier address on North Belmont Avenue, I was surprised to find an elegant mansion that once served as Wichita’s art museum. Confused, I wondered if I should be looking for Fines’s residence on South Belmont.

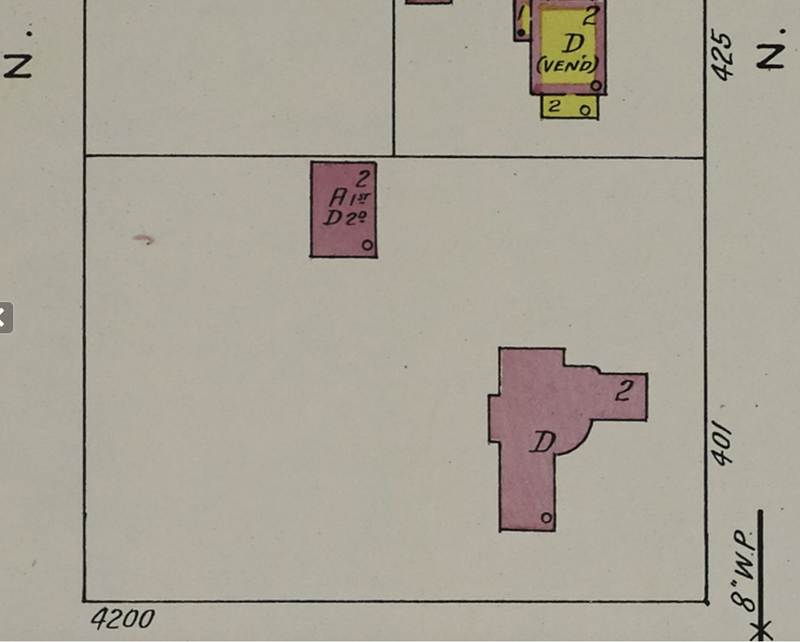

Eventually I discovered the home’s owners: Lou Rogers Hurd, who headed a mill elevator company, and his wife, Fannie. Fines lived with them because, like 40% of black women then, she was a domestic worker. Her husband was the Hurds’s butler. The house had recently been for sale, so I scoured photos of its interior, but there seemed to be no space in it to board employees. Sanborn fire insurance maps revealed the location of an apartment where the Fineses originally lived atop a garage. It is now transferred to an adjacent property and has been converted into an opulent AirBnB.

Mollie’s status as maid during the 1920s when she served as an officer for the leading organization for Black women contrasted with the upper-class status of many NACWC leaders, some of whom might have viewed her as requiring “uplift.” Her living situation also underscored the segregation of Black and white women’s music making. Fannie Hurd hosted the Saturday Afternoon Musical Club she had helped found in her home. Fines did not sing for Mrs. Hurd’s group, but could well have cleaned the house before their meetings or served them refreshments. Mollie’s own Harry T. Burleigh Club, named for the famous Black singer and composer, met in her garage apartment.

Fine’s brief engagement with the NACWC at the national level, appears to have been personally transformative. It is evidently not coincidental that in her song, she stressed the importance of education, something the organization promoted. In 1925, while still working for the Hurds, Fines announced she was going back to college. The Negro Star reported on her graduation recital, at which enthusiastic admirers covered the piano in flowers. Fines studied at the Three Arts Conservatory and attended “night school,” probably Wichita Municipal University’s extension program.

I was unfortunately unable to document Fines’s educational endeavors. The friendly archivist at what is now Wichita State University could find no trace of her, nor could the librarian I contacted at Philander Smith College in Little Rock, Arkansas, which Fines stated she attended in her youth. Additional mysteries remain. Multiple dates are given for her birth, and the reason she and her husband went by “Fines” rather than his given name, “Fine,” is unclear. Mollie Fines reportedly continued to compose, but none of her other compositions has survived.

As I researched Fines, I came to admire her as someone who, whenever she encountered a new musical experience, used it to make opportunities for herself. After Fines sang solos in a 1925 pageant about black history, she began producing pageants herself. In the 1930s, she created The Heavenbound Wayfarer, featuring spirituals and gospel hymns, directing performances of it in Kansas and Nebraska. Later that decade, perhaps inspired by the Wichita visit of the famous Hall Johnson choir, Fines conducted her church choir in monthly Sunday evening sacred concerts and in radio broadcasts. Not all of what Fines called her “experiments” were successful, but she continued to take on creative initiatives throughout most of her adult life.

In 1951, Fines donated her personal music collection and grand piano to the NACWC’s headquarters in Washington, D.C. Her gift demonstrates that she felt that her own musical efforts were deeply intertwined with her membership. Over two decades after she served as the NACWC’s music director, her former position was regularly reported next to her photograph in the Kansas Association’s meeting programs. Fines’s club experiences transformed the way she thought about herself, inspiring her lifelong musical activities.

Notes

An earlier WSF post of mine deals with Mollie Fines, “Lifting as We Climb,” and the NACWC. She is the subject of a lengthy chapter in my forthcoming book about clubwomen activists and American music. Scholarship about the NACWC sometimes mentions Fines’s song, citing an article in The Crisis that calls her “Marie,” not “Mollie.”

For Further Reading:

Brady, Marilyn Dell. “Kansas Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs, 1900–1930.” Kansas History 9 (Spring 1986): 19–30.

Davis, Elizabeth Lindsay. Lifting as They Climb. Washington, DC: National Association of Colored Women, 1933; reprint ed., New York: G. K. Hall, 1996.

Wesley, Charles H. The History of the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs, Inc. Washington, DC: NACWC, 1984.

White, Deborah Gray. Too Heavy a Load: Black Women in Defense of Themselves, 1894–1994. New York: W.W. Norton, 1999.

Williams, Doretha K. “Kansas Grows the Best Wheat and the Best Race Women: Black Women’s Club Movement in Kansas 1900–30.” PhD diss., University of Kansas, 2011.