Alan Lomax recorded almost 1,500 folk songs throughout Spain between June 1952 and January 1953. The material results of his journey, which are preserved at the American Folklife Center of the Library of Congress in Washington, DC, include music on magnetic tape, but also photographs, field notebooks, invoices, annotated maps, letters, diaries, and even the manuscript of part of a book for publication.

Why did Lomax undertake fieldwork in Spain? Columbia Records had commissioned him to bring together a series of folk music albums, each of which would be devoted to a country or region. One would be dedicated to Spain. Lomax wrote to Walter Starkie, an Irish musician and writer, director of the British Council in Spain, asking for guidance to help him find a Spanish folklorist with experience in field recording. Starkie replied that Spanish ethnomusicologists continued to write the music down by hand. Given the impossibility of finding a collaborator with the required equipment and experience, Lomax, who was living in Paris at the time, decided to attend the Folklore Festival and Conference to be celebrated in Palma in June 1952. It would, he assumed, be a good opportunity for networking.

The coordinator of the festival was Marius Schneider, a German musicologist who had been appointed director of the Folklore Division of the former Spanish Institute of Musicology. According to Lomax, when Schneider learned about his project, he stated that he would personally see to it that no Spanish musicologist would help him. It was this encounter that led Lomax to make a promise to himself that he would record in Spain. The main source of funding was the BBC in London, which was planning a series of broadcasts on Spain. Lomax offered to provide them with recordings if they financed his trip and that of his British assistant, Jeanette Bell (1917–2018).

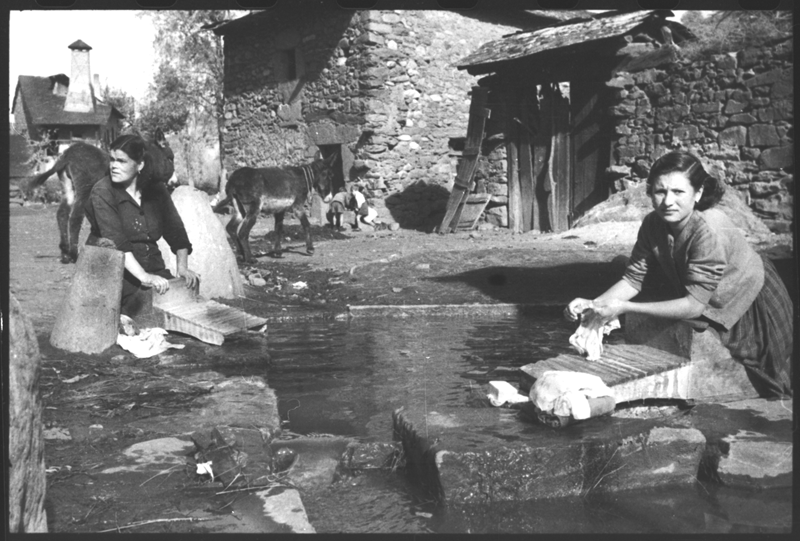

Lomax’s sound recordings offer a unique opportunity to approach the political situation under Franco’s dictatorship, the poverty of the country, and the moral constrictions faced by women through the eyes of Lomax and Bell. Lomax showed a special interest in Spanish women’s lives and his documents contain constant references to Bell, reflecting the important role that she played in making up this collection.

Alan Lomax’s journey across Spain: Cataloguing and mapping the collection

As a first stage of my research, I incorporated the details provided by the Lomax collection into the database Fondo de Música Tradicional IMF-CSIC, cataloguing information on all the places visited by Lomax, and all the songs and people recorded there – including his photographs and links to audio files in the Association for Cultural Equity online archive. The material was catalogued by listening to the songs and consulting Lomax’s notes on the original reel boxes, along with his diaries and notebooks. I also analyzed, catalogued, and transcribed around 250 documental units such as field notebooks, annotated maps, letters, and diaries, connecting them to the music, people and locations to which they refer, and including links to the corresponding digitization on the Library of Congress website.

This stage prepared the collection for analysis and comparison, and it is possible to identify concordances between Lomax’s recordings and other collections of Spanish traditional music compiled around the same time, such as that preserved at the Spanish National Research Council in Barcelona. The Barcelona collection is primarily made up of more than 20,000 folk songs copied on paper and collected throughout Spain between 1944 and 1960, most of them through the so-called “folkloric missions” and competitions organized by the former Spanish Institute of Musicology.

The Barcelona collection includes, for instance, several songs performed by Dolores Fernández Geijo, a woman from a small Castilian village, in the form of transcriptions made by the Spanish ethnomusicologist Manuel García Matos in 1951. A year later, Lomax recorded twenty songs performed by the same woman in the same place, and some of them coincide with those transcribed by García Matos, as in the example here.

In order to provide a different approach to the collection, I created an intricate StoryMap which presents Lomax’s itinerary as he travelled across Spain. I have connected each of the dozens of towns to the audio playback of an example of the music that he recorded there. These are also linked to one of 89 relevant images belonging to the Lomax Collection, and to a link to the complete information concerning that location on the database (further information here).

The work of Jeanette Bell

Lomax’s documents contain constant references to Jeanette Bell and reflect the important role that she played in helping Spanish women open up for the recordings and talk about topics that they would never have discussed with a man, such as marital life, sexuality, and mourning. Although some scholars have stated that Bell travelled from Paris to Palma with Lomax in June, the documents confirm that she joined Lomax in August in Barcelona. In his field notes Lomax wrote about Bell in July, announcing that she was to go to Spain.

Lomax had written about her when he was living in Paris, before his journey across Spain, indicating that they had a previous relationship and references to their changing feelings for each other are scattered throughout the documents. In a letter to his ex-wife, Elizabeth, Lomax defined Bell as his “secretary and companion.” She was described in the records of the US embassy in Madrid as “a slender woman with a British passport, green eyes, 30, blond,” and was registered in accommodation records as Lomax’s wife.

Scholars had stated that Bell was an assistant provided by the BBC, but there is no evidence that the BBC had ever employed her. According to Lomax’s diaries, Bell had no experience in this type of fieldwork. She herself wrote at the beginning of the trip that this was the first time that she had been “in the field” with Lomax, that she “put the reels on backwards on the machine, and then sat aside and took no more part in the proceedings.”

Bell’s writings are scattered among Lomax’s papers, so that, at first, they could be confused with texts written by Lomax himself. They were typed up after the end of the trip and begin with a description of Bell’s arrival in Barcelona airport in August 1952 and her encounter with Lomax. They also contain comments on her experiences throughout their journey, her role in the recording process, and her feelings and emotions.

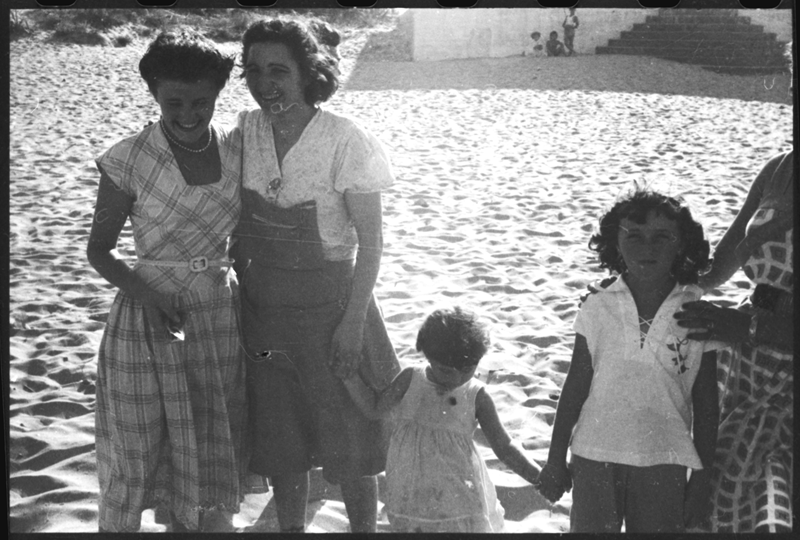

These memoirs – as with Lomax’s own diaries – demonstrate her connections with Spanish women; for instance, learning to dance with young girls, or trying on traditional women’s costumes. She also explained her experience when Lomax left her to record a group of young girls on her own and used up all the tape they had to spare. She even wrote that “Spanish women were the nicest people” she had ever met. Bell was also skilled at talking with men. When Lomax reported on his fieldwork in the north of Spain, for example, he wrote that while he recorded, a young man told Bell some of the things the folks wouldn’t have told him about the sex life in the area.

Lomax and Spanish women

Bell’s memoirs are very rich in comments on the particularities of Spanish female culture. To cite just one: she commented on her conversations with women from the Maragato region in the province of León. A 26-year-old widow explained to her that, before marrying, women used to have a boyfriend for more than ten years and that when a husband died, his wife had to wear black clothes forever. In a program for the BBC, Lomax explained that, in these villages, men went away to earn a living, while women stayed at home, “jealously guarding each other’s honor and doing all the heavy work in the fields.” Lomax’s writings reflect the cultural shock caused by the strong moral constrictions imposed upon women in Spain. Among others, he wrote extensively on a group of girls who were prevented by their boyfriends from going to his hotel for a recording session.

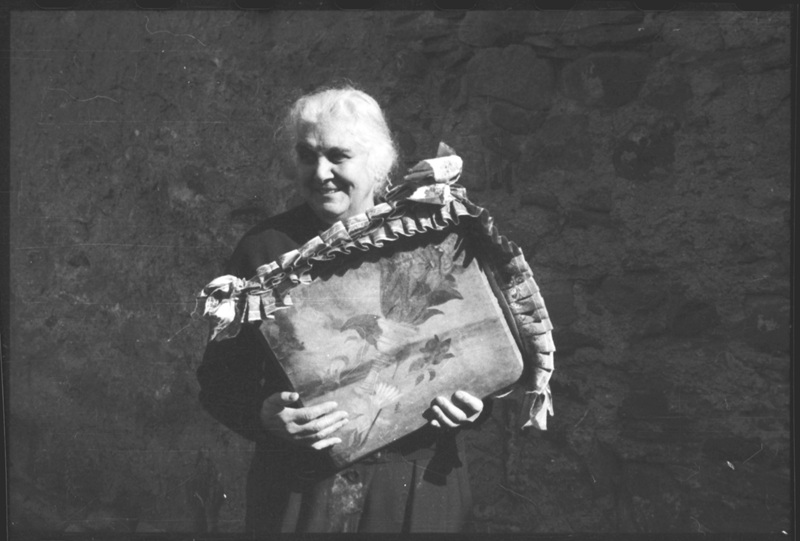

The experiences of old women also received particular attention. Lomax asked one of his female informants to write her biography and to send it to him. A further case is that of Carolina Geijo, an old woman who was interviewed in the presence of her sister. A conversation in which Lomax asked her if women worked more than men, is recorded, while a more formal interview is written down and it is not clear if it was made by Lomax or Bell – in this part the informant talked about more private issues such as her childhood, courtship, marriage, and pregnancy.

Spanish women talked to Lomax and Bell about their lives, but also sang songs related to their traditions. We can listen here to a wedding song, performed by this woman, her sister, and her daughter. The song, which was usually performed when the bride arrived home after the wedding ceremony, was recorded in these women’s kitchen.

Or we can listen here to another wedding song, performed by a group of women from a Castilian village, where the playing of square frame drums held particular association with women.

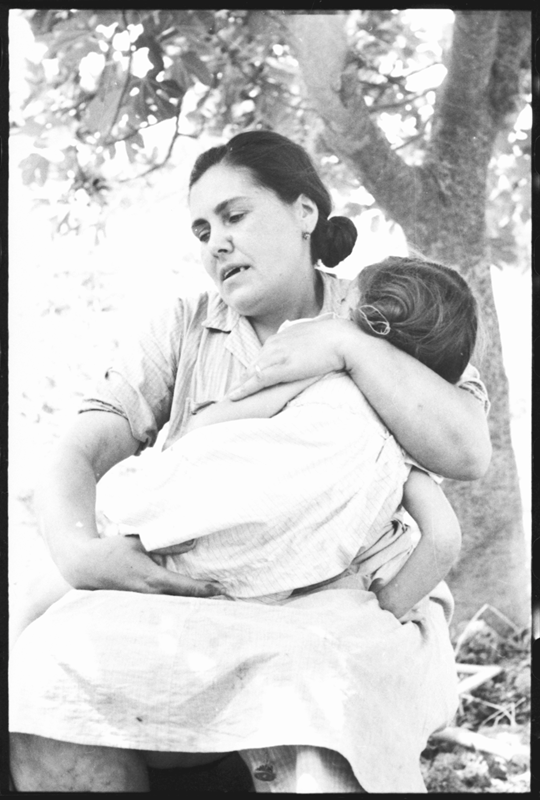

Lomax thought that folklore was something that lives and changes, especially in the country. He considered that folk music was music that had not been arranged; this is contrasted with the official folk music of Spain from that period. In one of his programs for the BBC he talked extensively about the differences he had found in women’s singing of lullabies between different Spanish regions, explaining that when he recorded lullabies he always “asked the [female] singer to hold a child in her arms.”

Women played an important role in the oral transmission of folk music in Spain. My previous research into the collection of traditional music preserved in Barcelona shows that the clear majority of the informants were women, particularly little girls and old women, and they had learned the songs from their mothers or grandmothers, or from other girls. In an essay Lomax explains that in his worldwide fieldwork he found features of song and dance that are specific to women. This was caused by the sexual division of labor in food production and the different approach of men and women to public interactions.

Lomax created some of the earliest systematic recordings of Spanish folk music and the material results of his journey offer only a pale reflection of the deep impact that his visits must have had on the inhabitants of all the small villages where he recorded. Lomax’s documents allow us to assess how women, from their own spaces, contributed to setting up this impressive collection of sound recordings.

Notes

The banner photo of Jeanette Bell was taken in Barcelona in June 1952 by Alan Lomax. From the Alan Lomax Collection at the American Folklife Center, Library of Congress. Courtesy of the Association for Cultural Equity.

Further information on Lomax’s collection of sound recordings is available here, and also in Ascensión Mazuela-Anguita’s recent book, Alan Lomax y Jeanette Bell en España (1952–1953). Readers who understand Spanish will also enjoy this presentation on her book.

For an earlier WSF post on women and Spanish folk music, see the essay on the Catalan-Spanish poet, folklorist, and composer Palmira Jaquetti Isant by Emilio Ros-Fabregas.

On the controversial figure Marius Schneider who lived in Barcelona from 1944–55, see Chapter 3 of Anna Maria Busse Berger, The Search for Medieval Music in Africa and Germany, 1891–1961: Scholars, Singers, Missionaries.

Guest Blogger: Ascensión Mazuela-Anguita

Ascensión Mazuela-Anguita is an Associate Professor in the Music Department, University of Granada. She is also the author of Artes de canto en el mundo ibérico renacentista; Women in Convent Spaces and the Music Networks of Early Modern Barcelona (2023); and most recently, Música y discapacidad visual en el mundo hispánico del siglo XVI: el organista y compositor Antonio de Cabezón. Additionally, she has published essays on convent music, and music in early modern urban ceremonial and traditional Spanish music.