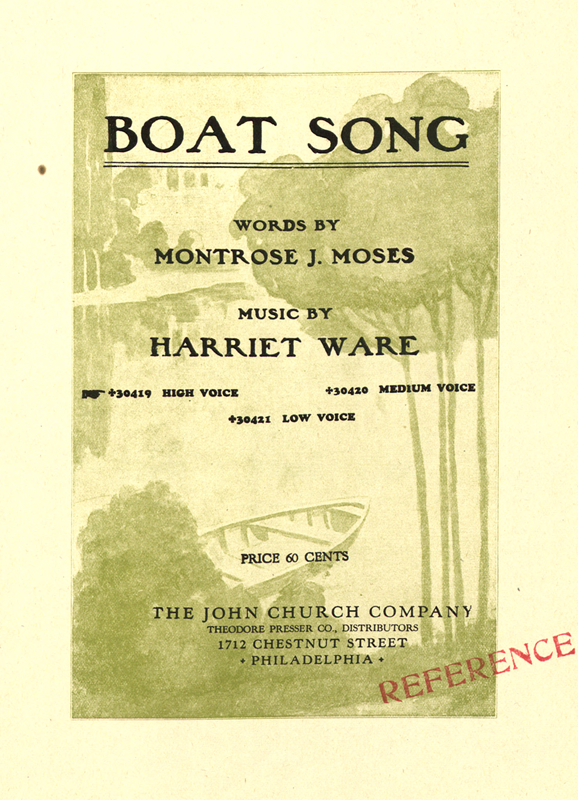

Harriet Ware composed “Boat Song” in a single day. The poem by Montrose J. Moses, imbued with nostalgia for the lazy summer days of childhood, addresses the little boat carrying its drowsy passenger, “Where will you take me, little boat, All on a summer’s day? Shall I dream and let you float, Whither away?” In Ware’s setting of the poem, her lyrical melodies float over a rippling piano accompaniment.

“Boat Song” became Ware’s most popular work, widely sung in North America, the United Kingdom, and Australia before World War II. In April 1908, while the song was still in manuscript, it was so successful at a recital in the ballroom of New York’s Plaza Hotel that it had to be repeated. Musical America predicted, correctly, that its dreamy “beauty and mystery” would find “instant favor with lyric singers.” Ware also programmed “Boat Song” at two concerts of her music held at Wannamaker’s Greek concert hall in Philadelphia that October. She was the only woman in the ongoing series of composers featured by the department store, which also included John Philip Sousa and Ethelbert Nevin.

By the time the composer appeared in concert in Chicago in 1913, the Musical Observer noted that “Everybody knows Harriet Ware’s ‘Boat Song’.” Two years later, in a poll of leading singers, several declared it one of their favorite American songs, and it eventually sold one million copies. “Boat Song” achieved acclaim because it was frequently programmed by two unexpectedly allied groups of singers: professional men and amateur women.

Her Supporters

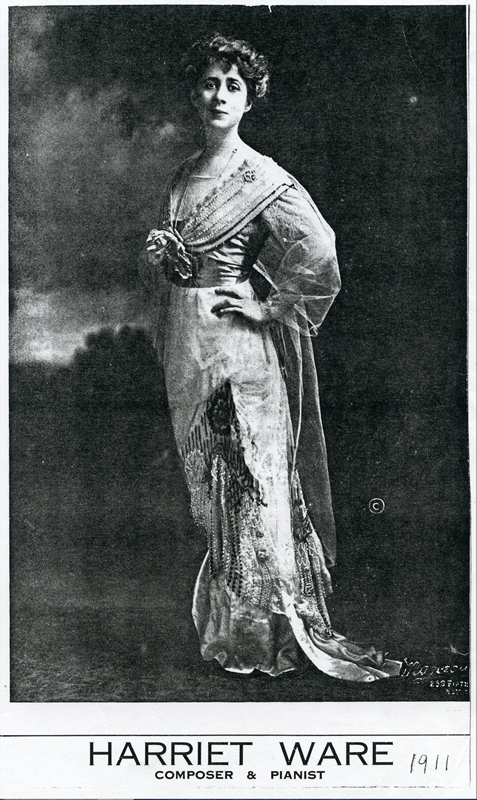

Harriet Ware (1877–1962) had a successful career as a song composer thanks in part to the women’s club movement. As a child, Harriet had lessons in voice, piano, and composition at the Pillsbury Academy in Owatonna, Minnesota. Although she pursued additional studies in New York and Europe, before 1913 Ware taught music and helped her mother run a boarding house in Garden City, New Jersey. It was probably her Minnesota roots that inspired the invitation to appear on the concert of women composers organized for the General Federation of Women’s Clubs’ national meeting in St. Paul in June 1906. Ware accompanied soprano Mary Hissem de Moss in three of her songs in an evening performance that also featured the music of such leading figures as Amy Beach, Clara Schumann, and Cécile Chaminade. The armory in which the concert took place held 3000 people. Having her works heard by clubwomen from across the country helped transform Ware’s career, as they began to take up her music.

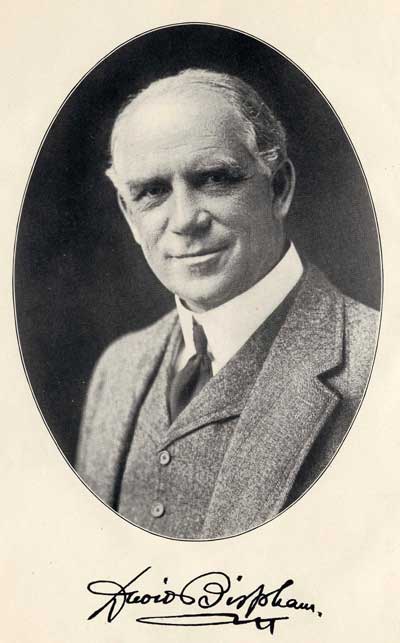

The most influential professional singer to program Ware’s music was operatic baritone David Bispham. He included “Boat Song” in his final set of “modern songs” on a recital sung entirely in English that he began to perform the year the song was published. Chicago critic Glenn Dillard Gunn found it “trite and conventional” but acknowledged how much the audience liked it, which would become a frequent reaction. Bispham toured from coast to coast, singing “Boat Song” over 500 times. His particular appeal to female audiences may also have helped the song’s popularity among amateur women singers. When Ware wed civil engineer, Hugh Montgomery Krumbhaar in 1913, Bispham sang her setting of Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s sonnet “How Do I Love Thee?” at the wedding.

An excellent pianist, Ware accompanied numerous singers in her works. In 1910 and 1911 she appeared on recitals with baritone Cecil Fanning, performing before the Thursday Musical, a Minneapolis women’s group, and in New Orleans under the auspices of the Philharmonic Society. Fanning also wrote the libretto for Ware’s cantata for women’s voices, St. Oluf, and sang the solo role. Ware often performed with the New York tenor, John Barnes Wells, who had first sung “Boat Song” in the Plaza’s ballroom. Reviewers praised Wells effusively. After he had to repeat “Boat Song” for an audience in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, in 1909, the local critic described his voice as “gleaming with nuances” and called the encore “certainly out of the ordinary.”

Audiences demanding that Boat Song be repeated became a typical event, occurring in Newark, Chicago, and elsewhere. The attraction was not simply Wells’s singing. A critic for The Washington Herald praised Ware’s playing and found that her accompaniments featured “the highest musicianship and poetic insight.” Wells recorded the song with orchestra, but it is his 1914 recording with Ware at the piano, his light tenor lingering expressively on high notes, that best captures what contemporary audiences found magical. Particularly in the second verse, the way he elides the end of a phrase with the beginning of the next, while shifting into falsetto, must have thrilled his audiences. It is worth comparing his version to that of David Bispham.

Although most recordings of “Boat Song” were by men – not only Wells and Bispham, but already by 1927 also Cecil Fanning, Louis Graveure and at least four other male singers – women frequently sang “Boat Song” in amateur settings. In 1923 Ware made two Welte-Mignon piano rolls of it, one a full version and the other advertised as accompaniment for a soprano. The song’s popularity also led to varied arrangements of it. Since many women’s clubs had choruses, an arrangement for three-part women’s voices was published in 1916 and again in 1930. When Helen Brown Read appeared with the Minneapolis Orchestra in November 1915, she sang “Boat Song” as an encore in a version with the “accompanying wavelets” heard in harp and flute, instruments also featured in the song’s early recordings. Read sang Ware’s song to the accompaniment of harp instead of piano in her 1917 recitals.

Clubwomen remained devoted to Ware, who served in the General Federation of Women’s Clubs’ Music Division in the 1930s. Ware, in turn, praised the work of women’s clubs, which she believed were “doing incalculable good for American music.” Some of Ware’s 63 published songs were heard at the General Federation’s meetings. It adopted her “Women’s Triumphal March” as their processional in 1927; a chorus of one hundred women sang it at their 1933 national gathering. “Boat Song” served as the theme music for GFWC radio broadcasts in the late 1930s. When Ware died in 1962, members of the Woman’s Club of Orange, New Jersey, helped fund the production of a memorial LP of her music. The album featured the Mormon Tabernacle Choir singing Ware’s choral works and soloists performing many of her vocal solos, including, of course, “Boat Song.”

Notes

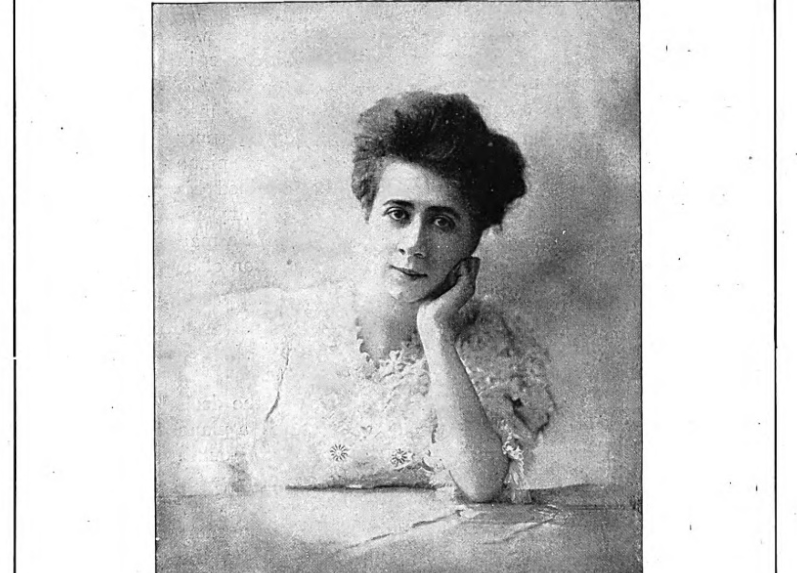

The banner photo appeared on the cover of Music Industry: A Monthly Magazine Devoted to the Piano and Allied Trades 2/11 (Nov. 1909).

“Americans Slight American Songs, Says Harriet Ware.” Musical America 25, no. 26 (April 28, 1917): 29.

“Harriet Ware, Concert Pianist and Composer, is Dead at 84.” The New York Times, February 11, 1962.

Joan Hylander, “Harriet Ware, ca. 1873–1962,” in Past and Promise: Lives of New Jersey Women (Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow Press, 1990), 415–16.

Heather Platt, “David Bispham and the Heyday of Song Recitals,” in Lieder in America: On Stages and in Parlors(Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2023), 167–195.