While combing through 19th-century newspaper reviews, articles and advertisements for my book about the song recitals that introduced American audiences to lieder, I encountered numerous women performers whose careers and achievements have yet to be acknowledged by historians of America’s musical life. One of these is Villa Whitney White (1858–1933), whose extraordinary recital in Denver I examined in Part 1.

In the decades before 1900 there was tremendous national interest in lieder and song recitals. Indeed, recitals became one of the most ubiquitous forms of entertainment in the United States. In 1895, White sky-rocketed to national prominence through her lecture recitals on the history of German song for the Amateur Musical Club in Chicago. Suddenly famous at the age of 37, she rapidly increased her touring schedule, performing across the country. Most of White’s programs emphasized German lieder and many featured complete lieder cycles. Her success was in large part driven by the rapidly growing number of women’s music clubs that sponsored recitals by nationally ranked artists, but also by Americans’ increasing interest in these German songs.

Unlike some of the earlier exponents of the lied, White was an American; her family had settled in New England during the 17th century. She began her career by performing lieder and 18th-century arias in chamber concerts in New England; by the end of the 1880s she was teaching at the Boston Conservatory and collaborating in concerts with other prominent Boston musicians, including the Eichberg String Quartet, America’s first women’s quartet. In 1891, she began studying with Amalie Joachim, the ex-wife of the famed violinist Joseph Joachim and one of the most acclaimed performers of lieder in Europe. Joachim was very fond of White; indeed, numerous sources cite White as her favorite student. White was the supporting artist in Joachim’s 1892 American tour, which saw them singing in Carnegie Hall. In 1893 Miss Mary B. Dillingham (1858–1949), a pianist from Minneapolis, became White’s main collaborator and companion, and she sometimes joined White on her annual journeys to Germany, where the mezzo soprano continued her studies with Joachim.

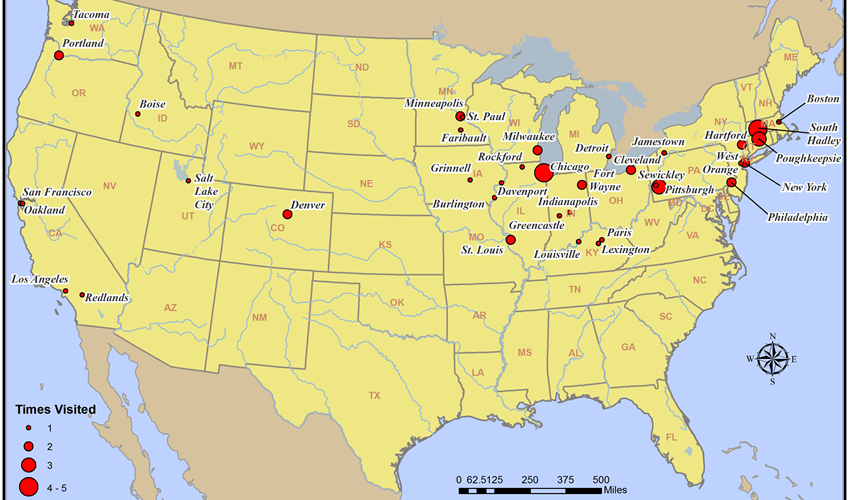

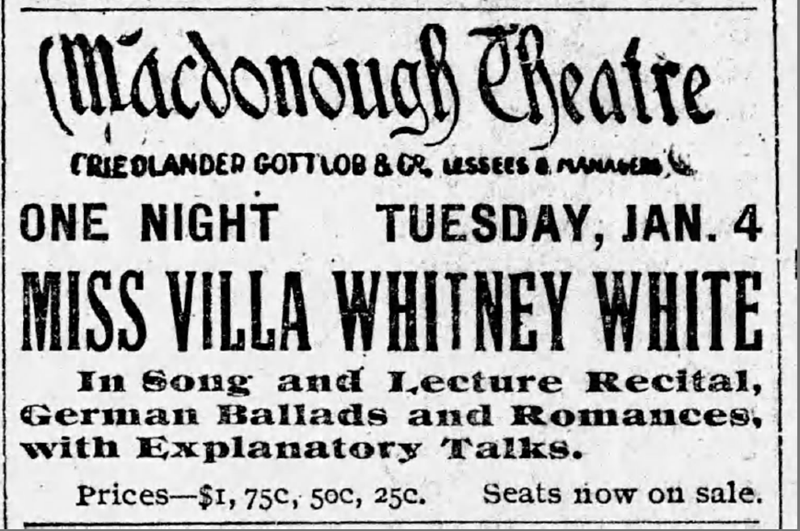

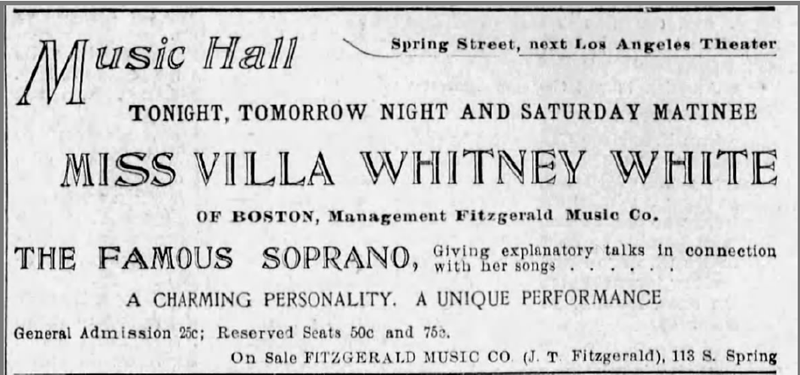

After their 1895 club performance in Chicago, the two women were almost constantly on tour. During 1896–98, they presented lecture-recitals in at least 45 cities in 22 states, giving two or three public recitals in each locale, in addition to performances in private homes of socialites and music lovers. Despite their full calendar of performances, White returned to Germany to study with Joachim for a few months each year. During these years she appeared before more than thirty women’s clubs. In many cases she was scheduled in club concert series that showcased acclaimed international instrumentalists such as the virtuoso pianist Leopold Godowski. In January 1895, the Saint Paul Globe observed that the efforts of the city’s Schubert Club to raise the standard of “music and musical ethics” could be no better served than by hosting three lecture-recitals by White.

During her performances, White placed each song in historical context and explained the meaning of the words. In general, she was more willing to push the comfort level of her audiences than her male colleagues. While they often sang at least some lieder in English, she sang only in German. Moreover, at a time when singing complete lieder cycles was highly unusual, White performed all twenty songs of Schubert’s Die schöne Müllerin at least thirteen times. In some places such as Minneapolis, the cycle had never been performed in its entirety. While international stars such as Ludwig Wüllner were reluctant to give full cycles on the West coast, White performed Die schöne Müllerin in Los Angeles and San Francisco.

Similarly, she gave numerous performances of a program comprising thirteen of the fifteen lieder in Brahms’s Magelone Romances. Indeed, one of the highlights of her 1898 tour was a performance of this cycle in Boston that was praised by Philip Hale, the city’s notoriously demanding critic. This cycle was considered so daunting for audiences and performers that only two men on the east coast had attempted it. However, at the Portland Music Club in Oregon in 1898, she performed this cycle on one night and then Die schöne Müllerin on the next. Despite the challenges these programs – or because of them – White commanded ticket prices that were more expensive than usual. She also gave numerous performances of at least three other cycles, Cornelius’s Christmas Songs, Alexander von Fielitz’s Eliland: Ein Sang von Chiemsee, and Beethoven’s An die ferne Geliebte.

White was a mezzo soprano whose rich middle and low registers were frequently praised. She assembled most of her programs with the assistance of Heinrich Reimann, the German organist, music historian, and librarian who had assisted Amalie Joachim in formulating her programs tracing the history of German song. Like Joachim, White performed lieder with texts that had a male narrative voice. This was the case with An die ferne Geliebte, Die schöne Müllerin, and many of the songs in the Magelone Romances, as well as with some of the individual lieder in her programs, including Brahms’s “Wie bist du, meine Königin” (“My queen, how rapturous you are”). Other women singers of the time also sometimes sang such male-voiced lieder, however in the subsequent century this practice changed and now they are almost always sung by men.

Among the dozens of easily available recordings of “Wie bist du, meine Königin” sung by tenors, baritones, or basses, Hermann Prey has one particularly worth hearing from 1974. But for generations after White dared to sing this song, lines like “let me perish in your arms! In them death would be … blissful” (“Laß mich vergehn in deinem Arm! Es ist in ihm ja selbst der Tod … wonnevoll”) were evidently uncomfortable when sung by a woman about another woman. Recordings exist by Elisabeth Schumann (from 1950, reissued in 2011), Kirsten Flagstad (1954, reissued in 1996), Janina Baechle (from 2015), and this exemplary performance by Cornelia Kallisch:

In contrast to stereotypical depictions of club women ignoring a presenter, White’s audiences were consistently described as attentive. According to reviews, her personal warmth, speaking voice, and ability to tailor her remarks to the audience’s level resulted in lectures that were as enjoyable as her singing. The Chicago teacher and critic, W. S. B. Mathews, himself a creator of lecture-recitals, distinguished White from other presenters: “Of singers there are many and of musical lecturers not a few, but the combined intellectuality and artistic endowment which is possessed by Miss Villa Whitney White is indeed rare.”

Despite her successes, after 1898 White refocused her career on teaching. In 1899, she took a teaching position at the Hartford Conservatory, where she had already established considerable influence and was a member of the Board of Managers. In addition, she served as the soloist at the Christian Scientist Church in Concord, NH, a position she held until approximately June 1903, when that community adopted congregational singing rather than using a soloist. Beginning in 1906, White collaborated with Calvin Cady, a leading music educator and a fellow Christian Scientist, in Boston and in Portland, OR. During her visits to Portland in 1897 and 1898 White established a strong network of friends and supporters. She frequently returned, establishing a home there around 1916.

White’s Impact

The popularity of song recitals peaked in the early 1900s, and by this time many eminent opera stars were touring the country presenting programs of new, challenging art songs by the likes of Debussy, Strauss, and Wolf. Stars such as Ernestine Schumann-Heink packed large venues, often earning more for recitals than for performances in operas. Their success was in part due to the efforts of women singers who had preceded them, including Villa Whitney White, and patrons such as women’s clubs. They helped to establish song and lecture recitals as profitable modes of entertainment.

White’s career trajectory was not typical for professional singers, and particularly not for a woman. Nevertheless, her success enabled her to compete in the busy 1896–98 concert seasons when numerous international song recitalists were touring the U.S. Her engaging explications of lieder texts helped her avoid the types of criticisms of German-language programs that were occasionally lobbed at some of her contemporaries. Other singers fully appreciated that the words and music were equally important in lieder. What set White apart was her ability to convey the meaning of a song to her audiences. We can imagine that her determination to sing entire song cycles grew out of this desire to communicate the full meaning of individual songs.

Notes

The photograph of Villa Whitney White from ca. 1898 is in the Hill Family Papers, scrapbooks 1892–94, in the William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan.

The map of White’s tours was designed by Angela Gibson, former GIS Specialist for University Libraries at Ball State University.

Das deutsche Lied: Eine Auswahl aus den Programmen der historischen Lieder-Abende der Amalie Joachim, ed. Heinrich Reimann, 6 vols. (Berlin: Simrock, 1895).

W. S. B. Mathews, as reprinted in “Musical Mention,” San Francisco Call, 12 Dec. 1897, 27.

Guest Blogger: Heather Platt

Heather Platt is Sursa Distinguished Professor of Fine Arts and Professor of Music at Ball State University. Much of her research has centered on Brahms’s lieder, their text-music relationships, musical structures, critical reception, and the women they portray. From 2007–2011 she served as President of the American Brahms Society. Her recent book is Lieder in America: On Stages and In Parlors. In it she chronicles the performances of women and men who contributed to the establishment of the song recital in the United States and the ways in which women’s clubs supported singers.