During the 19th century a wide variety of clubs, organizations, and institutions throughout the country regularly hosted public lectures and lecture-recitals. While many of these presentations were warmly received, as early as 1879 a newspaper article subtitled “Mania for Instruction” derided the “improvement mania” of women’s clubs and repeated an anecdote of a woman knitting during a parson’s lecture. Despite this attitude, which was not uncommon, presentations for women’s clubs given by nationally ranked authorities were often insightful and even innovative.

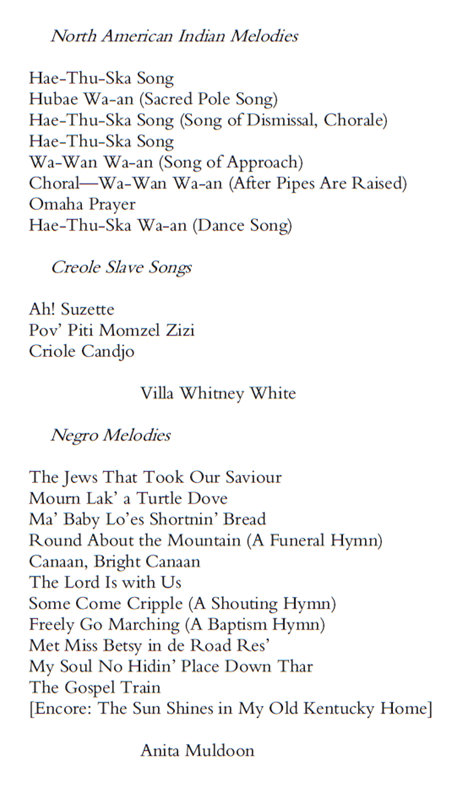

An extraordinary example of a substantive presentation was the lecture-recital on diverse American folksongs that Villa Whitney White (1858–1933), and her collaborators Anita Muldoon (1866–1909) and pianist, Mary B. Dillingham (1858–1949), gave to the Fourth Biennial Meeting of the General Federation of Women’s Clubs in 1898, in Denver.

White toured the country during the years 1895–98, giving lecture-recitals on the history of lieder and folksongs from Germany and the British Isles. Her career climaxed in 1898 with a highly publicized lecture-recital on the wide range of American folksongs for the conference of the General Federation of Women’s Clubs. By then, the Federation encompassed almost 600 clubs and the conference was attended by representatives from 42 states. This was the largest Federation conference to date, and its size and the strength of its program were attributed to Ellen (Mrs. Charles) Henrotin, the president of the Federation.

White’s program was highly unusual for the time because it encompassed African American, Native American, and Creole songs, which were performed in their original dialects, as well as songs by white composers dating from 1770 to 1865. White, influenced by her work with the German historian Heinrich Reimann, and by contemporary discussions in the United States, made the argument that all the types of songs on her program were being absorbed into the wider culture and becoming folksongs, a viewpoint that a growing number of people shared. Others adamantly refused to accept this view. According to them, African American and Native American songs were not truly American.

White and Muldoon had no experience with these types of songs prior to being contracted for their recital in 1896. Indeed, the theme of the program was likely created by Ellen Herotin and Eva Perry Moore, who arranged the performances at the conference. The selection of some of the repertoire was guided by Frederick W. Root, a revered singing teacher and composer in Chicago who organized an international folksong concert that was held in conjunction with the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. Although it was dedicated to showcasing songs from across the globe, its selection of a few songs by Blacks, indigenous Americans and white composers shaped White’s program. Her selections were also influenced by Mildred J. Hill, an influential music historian, pianist, and composer in Louisville who researched the songs of slaves and their descendants. Root and White had met in Chicago where they were both associated with the Amateur Women’s Music Club.

The Omaha Indian songs that White performed had been published only shortly before, with European diatonic harmonies and performance instructions supplied by John Comfort Fillmore, in Alice Fletcher’s acclaimed Study of Omaha Indian Music (1893). According to newspaper reports, White quoted this publication during her lecture. Although she sang in dialect, she indicated that she was not replicating the “nasal” timbre she believed was typical of the original performers (Denver Daily News, 25 June 1898). She told her audience the songs were characterized by duple and triple rhythmic groupings and that drums were traditionally used. But it seems that she did not use them during her performance.

The three Creole songs that White performed had been published in an article by George Cable in the Century Magazinein 1886, where “Criole Candjo” appeared in an arrangement by Henry Krehbiel, the influential music critic of the New York Tribune who subsequently published the three songs that White sang in Afro-American Folksong: A Study in Racial and National Music (1914). Here is a performance of the Creole slave song, “Pov’ Piti Momzel Zizi” (Poor Little Miss Zizi) which White sang. Her pianist likely used George Cable’s accompaniment, which is not the same as the one in this recording.

The scores of at least eight of the songs that Anita Muldoon sang had been transcribed by Mildred Hill, who had learned them from African Americans in Kentucky, and Muldoon had similarly collected a few of the others. In an interview prior to the performance, Muldoon echoed themes propounded by earlier writers; in particular, by those responding to the 1893 premiere of Dvořák’s New World Symphony. Many of her observations were likely influenced by Hill, as they are almost identical to information in Hill’s articles from 1892 and 1895.

While learning songs for her presentation Muldoon came to understand the importance of preserving old songs such as the ones she performed: young Blacks were forgetting them. In her publications, Hill noted the importance of sorrow and suffering in African American songs, yet reports of the Denver recital give no indication that either White or Muldoon ever mentioned this important characteristic. Similarly, Muldoon sang in dialect and reviews described the ways that this music departed from European traditions, yet there is no acknowledgment that a Black singer would likely have performed these songs in a different manner, a distinction that Hill had drawn in her 1895 article.

Muldoon concluded her part of the program with an enthusiastically received encore. But rather than singing another African American number she gave Foster’s “My Old Kentucky Home.” Today, this choice would be unacceptable because of Foster’s association with minstrel shows and this song’s prominent place in such shows, as well as the original lyrics’ derogatory reference to Blacks. Neither Muldoon nor her audience registered discomfort; indeed, this song was one of those that Frederick Douglass had praised for its potential to “awaken the sympathies for the slave, in which anti-slavery principles take root, grow, and flourish.”

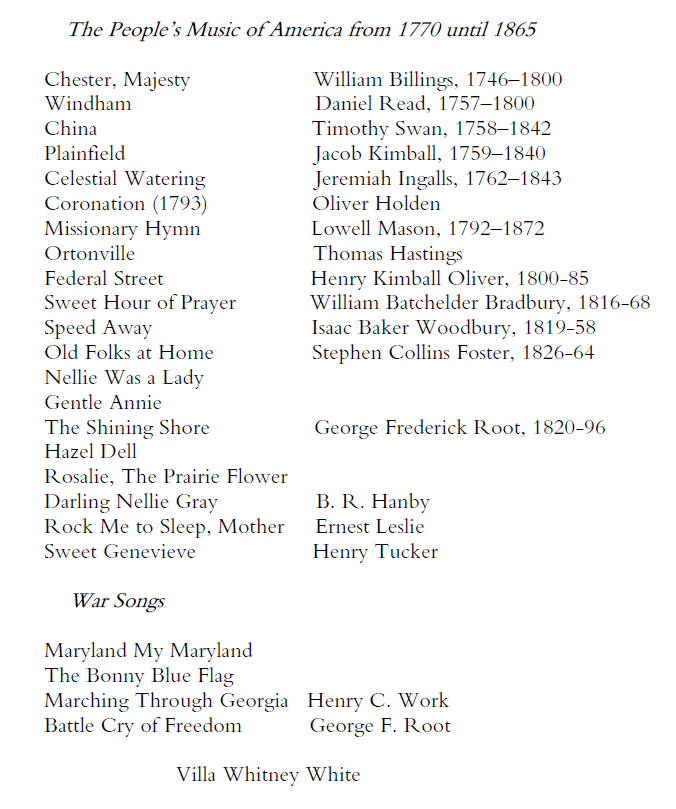

In contrast to the songs of the first half of the program, those of the second half were well known. However, the title of this set, “The People’s Music of America from 1770 until 1865,” reveals a disconnect between White’s claims that all the songs on the recital were American folksongs, because it implied that the songs of the first half were not “the people’s music.” No one commented on this, and it seems unlikely that the audience would have contemplated this problem.

The 1,600-strong audience responded enthusiastically to both White and Muldoon, applauding after many of the songs, and White concluded the event by leading everyone in a chorus of “The Battle Cry of Freedom.” While many of the reviews were enthusiastic, at least two critics registered discomfort with the unfamiliar dialect in a few of the songs on the first half of the program. Similarly, despite her commitment to African American songs, Muldoon showed no appreciation for Native American music, which she described as “merely a succession of shouts and howls,” and she devalued Creole songs because she believed they were derived from other countries (Louisville Courier Journal, 26 June 1898).

Similar types of disparaging remarks were voiced in response to a variety of other discussions of these repertoires. So common were the negative assessments of Native American songs that one of the reviewers of the performance addressed the issue head on: “To a person hearing their singing for the first time there is little in it but noise, but after dropping prejudice and a careful study, it can be found that the Indian songs served to express every feeling and emotion of the human heart” (Denver Post, 26 June 1898).

After the Recital

Despite their success, Villa Whitney White and Anita Muldoon did not reprise the complete program in subsequent engagements. Muldoon performed some of the African American songs in recitals for women’s groups in Louisville and St. Louis, and White gave the songs by white composers in recitals on the East Coast. Nevertheless, this does not distract from the significance of the recital.

The substantive and inclusive nature of the program sets it apart from programs comprised of popular coon songs and from performance in which singers appropriated Native American and African American clothing (or, worse still, black face performances). The program also anticipates similarly diversified programs by later singers, including Jeanette Robinson Murphy (1865–1946) and Nelda Hewitt Stevens (1888–1948), as well as the trend among acclaimed recitalists, including Marcella Sembrich (1858–1935), Ernestine Schumann-Heink (1861–1936), and David Bispham (1857–1921), to include one or two African American and Native American songs in their programs.

That the recital was the featured performance at a national conference of woman’s clubs, which was primarily devoted to social causes, is also significant. Unlike the stereotypical image of women chatting through recitals, it highlights women’s interest in learning about the diverse range of music in their country.

In Part 2 of this post, I will explore Villa Whitney White’s career, focusing on her tours of 1895–98. There is much to say about this influential but little-known woman.

Notes

For more detail on this post, see Heather Platt’s recent book, Lieder in America: On Stages and In Parlors (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2023).

The banner photo is cropped from a photograph taken ca. 1898. It is in the Hill Family Papers, scrapbooks 1892–1894, in the William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan.

“Flower and Folk Songs,” Denver Daily News (25 June 1898).

“Folk-Songs,” Denver Post (26 June 1898).

“Musical Matters,” Louisville Courier Journal (26 June 1898).

Frederick Douglass, My Bondage and My Freedom (1855).

Alice Fletcher’s Study of Omaha Indian Music (1893) is available digitally through Hathitrust; so, too, is George Cale’s April 1886 article, “Creole Music.”

On Mildred Hill, see Michael Beckerman, “‘Rare in a Generation of Remarkable Women’: Mildred Hill, Dvořák, Black Street Cries and the Making of ‘Happy Birthday’,” Journal of Czech and Slovak Music 28 (2020): 7-50.

Mildred Hill signed her articles as Johann Tonsor. “Negro Music,” Music 3 (1892-93): 119-22; and “Unconscious Composers: The Characteristics of Street Cries,” Courier-Journal (27 March 1895), Sec. 4, p. 1.

Henry Krehbiel, Afro-American Folksong: A Study in Racial and National Music (1914).

Ernestine Schumann-Heink has figured prominently in earlier WSF posts about Carrie Jacobs-Bond and Mary Turner Salter.

Guest Blogger: Heather Platt

Heather Platt is Sursa Distinguished Professor of Fine Arts and Professor of Music at Ball State University. Much of her research has centered on Brahms’s lieder, their text-music relationships, musical structures, critical reception, and the women they portray. From 2007-2011 she served as President of the American Brahms Society. Her recent book is Lieder in America: On Stages and In Parlors. In it she chronicles the performances of women and men who contributed to the establishment of the song recital in the United States and the ways in which women’s clubs supported singers.