In Part 1 of this post we examined how consistent breathiness portrays derealization (or a disconnect from the world) in “Me and a Gun” by Tori Amos. Among numerous other songs that use breathiness in similar ways are “Sullen Girl” by Fiona Apple and “5AM” by The Anchoress. In this post we turn to “Dog Teeth” by Nicole Dollanganger, to explore how reverb portrays depersonalization (or a disconnect from the body), and to “Gatekeeper” by Jessie Reyez. Its use of heavy vocal distortion portrays a dissociative disconnect from reality, in contrast to more feminine vocals that are more obviously performed by Reyez herself.

“Dog Teeth” by Nicole Dollanganger

Nicole Dollanganger’s “Dog Teeth,” from her 2012 album Curdled Milk, is also about sexual violence. While she does not specify her exact experience with sexual assault, she does say that “90% of the time” she writes about “things that [she has] experienced.” She says, “I write better from my personal perspective than an outside perspective” (Doherty 2015). Since she has many songs about sexual violence, I find it fair to assume that it is, unfortunately, something that she has experienced. In this song, a serial rapist, who she says is “all over [her],” is compared to a dog, as she describes him telling her to “pull out his teeth, because as long as he’d had them, he’d used them to do bad things.”

Vocally, this song has some distinct similarities to Tori Amos’s “Me and a Gun.” First, even though the song isn’t a cappella, the texture is thin enough that it feels similar. Dollanganger’s light, child-like voice is accompanied only by held out piano chords with quite a bit of space in between them, exposing her voice all by itself in between chords. Her voice also stays relatively consistent, as she sings through two melodically and timbrally similar verse-chorus cycles. However, Dollanganger’s striking baby voice drastically changes the aural experience, and she incorporates something that Amos does not: reverb.

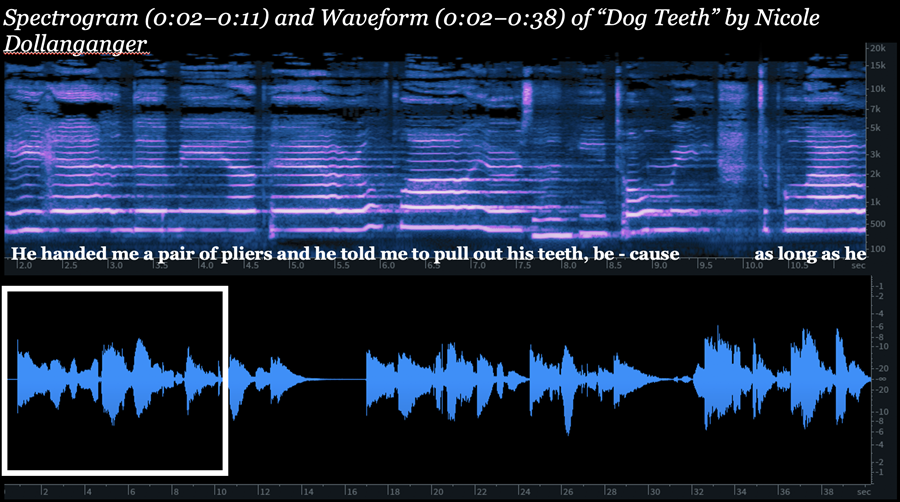

On the spectrogram and waveform below, you can see the evenly fading tails on each sound, which occurs from all the repeated sounds losing volume with each iteration. While Amos’s voice is small, front, and center in a tiny sonic space, Dollanganger’s voice bounces around the space like a racquetball. It sounds as if Dollanganger’s voice travels across and around a big “room” and away from her body. Just as someone experiences looking at themselves from across the room as they experience depersonalization, the sound does not stay grounded in one spot and, instead, seems to float around the various walls and corners of the sonic space.

Another song that uses reverb to convey similar feelings of dissociation is “Motion Sickness” by Phoebe Bridgers.

“Gatekeeper” by Jessie Reyez

In 2017, Canadian singer-songwriter Jessie Reyez released her first EP, Kiddo, including the track “Gatekeeper,” in which she responds to producer Noel “Detail” Fisher’s quid pro quo sexual harassment and assault. The lyrics are direct quotes from that night. Reyez describes the writing process for this song, saying, “it came out in a linear fashion – exactly how I’m singing it, that’s how the event happened. It’s all quotes, it’s insane” (Mapes 2019).

To begin the song, Reyez uses a mix between chest and head voice with added which, though quoting her abuser, seems to be coming from herself. The use of the feminine mixed voice seems to convey Reyez’s personal reflection, which is reinforced aurally with the added reverb to make it sound as though these thoughts are bouncing around in her head. In the music video, we see a portrayal of Reyez as a little girl singing the lyrics into a toy microphone. This childhood imagery reinforces the tragedy of this trauma, as well as trauma’s ability to revert our thoughts and feelings into a childhood state.

In the bridge, a low, manipulated voice is present as important lyrics from the verses are reiterated: “we are the gatekeepers, spread your legs, open up, you could be famous, girl, on your knees, don’t you know what your place is?” In this section, the music video shows a portrayal of her abuser yelling at her in a car as she descends into her flashback and disconnects from reality.

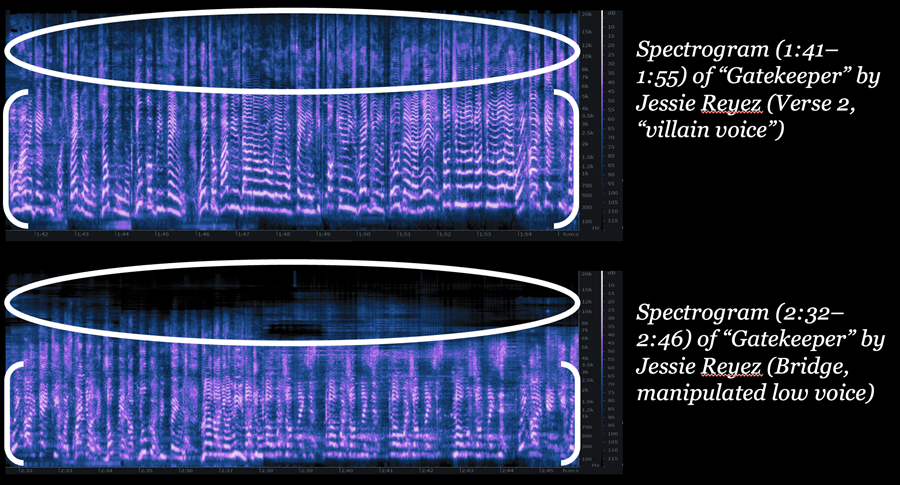

This low voice, though imitating her abuser, is actually a distorted version of Reyez’s own voice, which one can see on the spectrogram below. The manipulated voice looks like a vertically squished version of her voice in verse 2, which is visible in the absence of higher partials and in the way that the overtones all occur lower and closer together. Throughout this song, Reyez’s voice changes from a feminine, head voice, to a more-masculine, rapped “villain” voice, to this even-more-masculine, electronically-manipulated low voice as she descends further into her experience of abuse from this producer.

As she goes through her memories of that night, the climax is experienced through her intrusive thoughts; she literally reenacts the harassment, as if it is happening in the present. This disconnection from reality, inherent in intrusive thoughts, or “flashbacks,” is another form of dissociation, in which you aren’t only disconnected from yourself and/or those around you, but from reality itself.

In both of these examples, as in Tori Amos’s song discussed in Part 1, dissociation is conveyed through vocal timbre in distinct ways. They both do, however, incorporate childhood sound and imagery. In “Dog Teeth,” Dollanganger uses a child-like voice, and in “Gatekeeper” Reyez uses imagery of her childhood self. In this way, they both draw on aspects of childhood to reinforce the intense fear that accompanies trauma, as well as the ways that trauma changes the brain in ways that remind us of being a child.

I am not claiming either that these are the only ways to portray dissociation, or that they inherently mean dissociation. Rather, I seek to demonstrate that with the support of lyrics discussing a traumatic experience, these are some of the ways I have found that singers portray dissociation. Significantly, the private and public acts of writing and performing poems and songs about trauma can provide healing to survivors. Listening to them does as well.

These songs can also show others, through the embodiment of sound, what trauma feels like. On a related but separate level, however, I aim to show through my analyses how the music industry’s culture of sexual assault affects the sound of the music the industry produces. In other words, the issue of sexual violence is not just in studios with no windows; it emerges in the music that we listen to.

Notes

The banner photo of Jessie Reyes was taken on 15 Dec. 2017 at Freddy Smalls in Los Angeles by Gari Askew II.

Bibliography for Parts 1 and 2:

Amos, Tori and Ann Powers. 2005. Piece by Piece. Portland, OR: Broadway Books.

Bain, Katie. 2021. “Women Making Music Study: Sexual Harassment is ‘By Far The Most Widely Cited Problem.’” Billboard, March 25, 2021.

Cox, Arnie. 2017. Music & Embodied Cognition: Listening, Moving, Feeling, & Thinking. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders: DSM-5. 2013. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing.

Doherty, Michael. 2015. “Nicole Dollanganger’s Music is Darkly Dolled Up.” Vice, June 8, 2015.

Duguay, Michèle. 2022. “Analyzing Vocal Placement in Recorded Virtual Space.” Music Theory Online 28, no. 4 (December).

Harper, Faith G. 2017. Unf*ck Your Brain: Using Science to Get Over Anxiety, Depression, Anger, Freak-Outs, and Triggers. Portland, OR: Microcosm Publishing.

Heidemann, Kate. 2016. “A System for Describing Vocal Timbre.” Music Theory Online 22, no. 1 (March).

Koriath, Emily Jaworski, ed. 2023. Trauma and the Voice: A Guide for Singers, Teachers, and Other Practitioners. Washington D.C.: Rowman & Littlefield.

Kreiman, Jody and Diana Sidtis. 2011. Foundations of Voice Studies: An Interdisciplinary Approach to Voice Production and Perception. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

Malawey, Victoria. 2020. A Blaze of Light in Every Word: Analyzing the Popular Singing Voice. New York: Oxford University Press.

Mapes, Jillian. 2019. “The Chorus of #MeToo, and the Women Who Turned Trauma Into Songs.” Pitchfork, October 23, 2019.

Parson, Erwin Randolph. 1999. “The Voice in Dissociation: A Group Model for Helping Victims Integrate Trauma Representational Memory.” Journal of Contemporary Psychology 29, no. 1, 1999 (March): 19−38.

Porges, Stephen W. 2011. The Polyvagal Theory: Neurophysical Foundations of Emotions, Attachment, Communication, Self-Regulation. New York: W.W. Norton & Compan, Inc.

Savage, Mark. 2019. “Musicians ‘face high levels of sexual harassment.’” BBC, October 23, 2019.

van der Kolk, Bessel. 2014. The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma. New York: Penguin Books.

Wallmark, Zachary. 2022. Nothing but Noise: Timbre and Musical Meaning at the Edge. New York: Oxford University Press.

Wright, Sarah E. 2020. Redefining Trauma: Understanding and Coping with a Cortisoaked Brain. New York: Routledge.