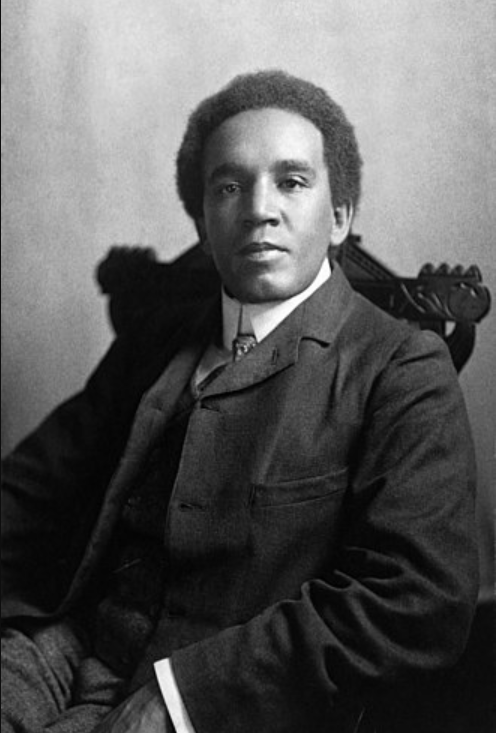

The list of concert works that went on to become pop-cultural hits is short, but it would certainly include London-born composer Samuel Coleridge-Taylor’s trilogy of cantatas – Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast, The Death of Minnehaha, and Hiawatha’s Departure – which set episodes from Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s epic poem The Song of Hiawatha. The U.S. premiere of Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast in Brooklyn in 1899 was only the first in a flurry of professional and amateur performances of the three cantatas that sprouted like weeds across the country in a fit of transatlantic “Hiawatha mania.”

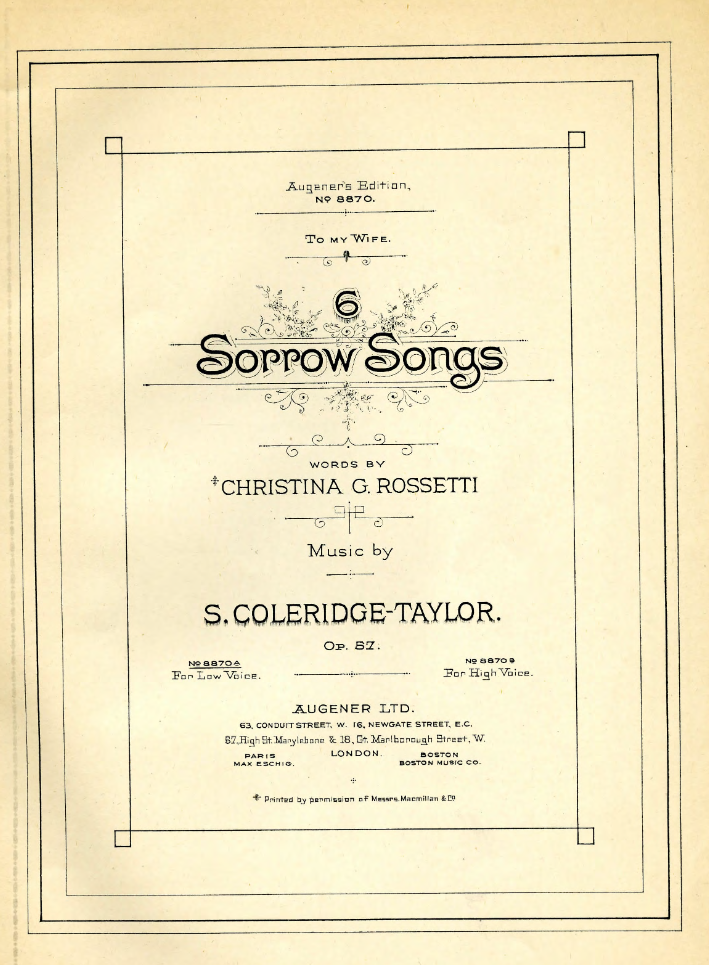

But Coleridge-Taylor, the son of an English mother and a Sierra Leonean father, established his most meaningful transatlantic connections through relationships with prominent African American artistic figures. In January 1904, Coleridge-Taylor read W. E. B. Du Bois’s recently published The Souls of Black Folk and declared it “about the finest book I have ever read by a coloured man, and one of the best by any author, white or black.” Du Bois’s rumination on spirituals in the final chapter of Souls, “Of the Sorrow Songs,” inspired Coleridge-Taylor’s Six Sorrow Songs, op. 57, written and first performed in 1904 and published in 1906.

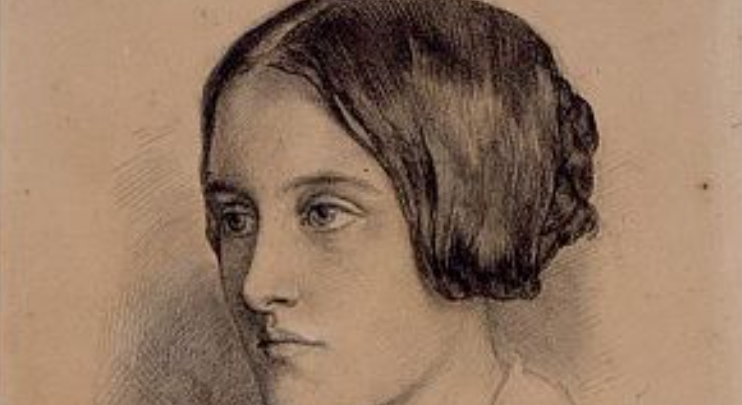

This song cycle brings another figure into the picture: English poet and writer Christina Georgina Rossetti, whose words gave voice to Coleridge-Taylor’s sorrow songs. Rossetti is commonly considered to be the most esteemed English woman poet of the Victorian era, rivalled only by Elizabeth Barrett Browning. No woman poet was more popular with women composers in the decades before and after 1900 than Rossetti. She came from an extraordinary artistic family of poets, painters, scholars, editors, and critics and she was recognized in her own lifetime, though after her death she enjoyed a new surge in fame around the turn of the century with the publication of a major life and works study in 1898 and the appearance of an edition of her complete poems in 1904. Thus, when Coleridge-Taylor picked up his pen to compose Six Sorrow Songs, he would have been witnessing exactly contemporaneous waves of attention given to The Souls of Black Folk and to Rossetti on each side of the Atlantic.

A recurring theme in Rossetti’s poetry is unreconciled dualities that are often manifest in what Winston Weathers has described as “the divided personality wanting to find its balance and peace.” One example of this tortured “fragmented self” is Rossetti’s 1866 poem “Who Shall Deliver Me,” one stanza of which reads:

I lock my door upon myself,

And bar them out; but who shall wall

Self from myself, most loathed of all?

The most famous concept delineated in The Souls of Black Folk – and one of the seminal ideas in twentieth-century intellectual history – is “double consciousness,” which W. E. B. Du Bois defined as the African American “sense of looking at one’s self through the eyes of others.” He elaborated by unreeling a chain of dualities: “An American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body.” For Du Bois, even the sorrow songs bear this doubleness, as he recognized them as “of me” yet “unknown to me.” We aren’t left with many concrete clues about how exactly Coleridge-Taylor intended his Six Sorrow Songs to commemorate Du Bois’s book.

Why this poet for this project? Perhaps the customary first-person perspective in Rossetti’s poetry wedded a personalizing “I” to the more theoretical abstraction of Du Boisian double consciousness. Whatever the case, the resonance and strategic convergence of Rossetti’s contemplation of the divided self and Du Bois’s explication of African American “two-ness” may have enabled Coleridge-Taylor to reflect upon and aestheticize his own liminalities – as both English and African, as politically aligned with African Americans yet culturally and historically askew – while also exemplifying the pervasive, turn-of-the-century modernist preoccupation with self-consciousness and fracture.

In the six Rossetti poems that Coleridge-Taylor selected for his Sorrow Songs, we encounter contrasting entities that offer the kinds of poetic conceits that poets love: land and sea in #1, the in-betweenness of twilight in #2, stages of life in #3, remembering and forgetting in both two and five. Many times, duality embodied by Rossetti’s narrators was expressed through the trope of sisters. If opera plots liked to exploit the device of sisters with contrasting personalities – Fiordiligi and Dorabella from Così fan tutte and Eugene Onegin’s Tatiana and Olga are two examples – Rossetti often explored what some Rossetti scholars have referred to as “self-sisters” or a “sisterhood of the self,” sisters being a metaphor for differing sides of a divided female subject.

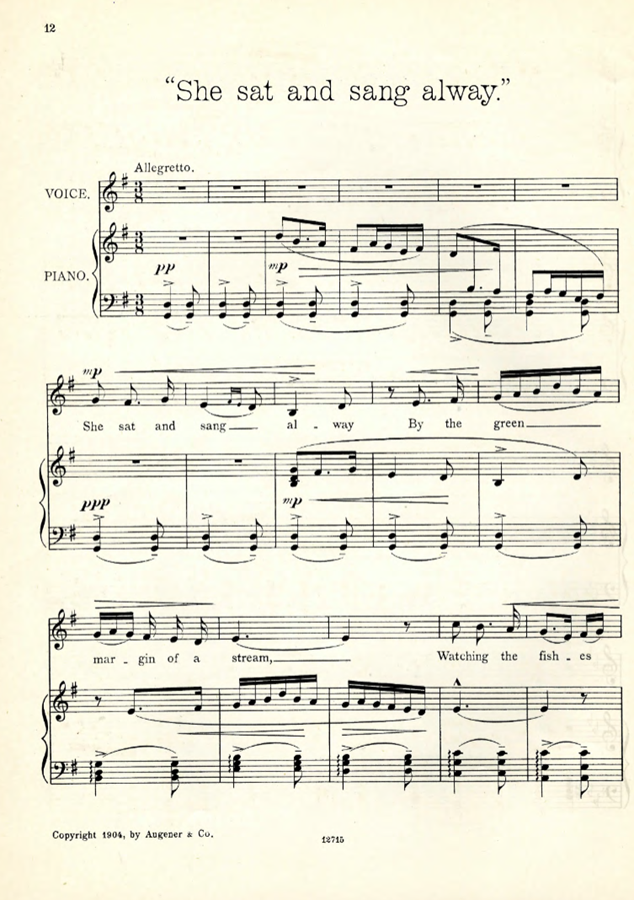

We see something gesturing toward this in the fourth song in the set, “She Sat and Sang Alway,” which originated as a poetic insertion in Rossetti’s 1850 story Maud, about two sisters, Maud and Agnes.

1. She sat and sang alway / By the green margin of a stream,

Watching the fishes leap and play / Beneath the glad sunbeam.2. I sat and wept alway / Beneath the moon’s most shadowy beam,

Watching the blossoms of the May / Weep leaves into the stream.3. I wept for memory; / She sang for hope that is so fair:

My tears were swallowed by the sea; / Her songs died on the air.

The poem is rife with dualities – singing and weeping, sun and moon, sea and air, hope and memory – but the dichotomy of “she” and “I,” understood as sisters in the original prose context but more ambiguous in the standalone poem, is suggestive of a sisterhood of the self. Are we encountering two sides of the same person? Two different people? Are they still sisters? Friends? An older self, reminiscing on a younger one? A metaphor for the frustrated aspirations of Victorian womanhood?

Coleridge-Taylor’s setting moves us through the poem with a shape-shifting piano accompaniment – resting on an opening hurdy gurdy-like drone – that morphs from a lilting, trochaic, long-short left-hand pattern in the pentatonic-leaning first stanza; to limping, iambic short-long rhythms folded into the sudden turn to the harmonic minor in the second stanza; to growing turbulence and chromatic-inflection in the climactic third stanza, as “she” and “I” are brought into closer comparative proximity. If the triangulation of Coleridge-Taylor’s African ancestry, British citizenship, and affinities for African American cultural-politics made him a quintessential Black Atlantic figure, his Six Sorrow Songs enacted dialogue between Rossetti and Du Bois, history and modern consciousness, and sound and language to harmonize his highly personal Black Atlantic desires.

In this performance of “She Sat and Sang Alway,” we hear English operatic soprano Elizabeth Llewellyn, who, like Rossetti and Coleridge-Taylor, was born in London. The recording comes from Llewellyn’s 2021 debut album Heart & Hereafter: The Collected Songs of Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, which includes the complete cycle of Six Sorrow Songs.

Notes

This post marks the third anniversary of Women’s Song Forum, the beginning of our fourth year. Mark Burford wrote our very first post and each anniversary post since.

Professor of English Mary Arsenault, musicologist Jada Watson, and others at the University of Ottawa have teamed up to produce a remarkable resource, The Christina Rossetti in Music Project, which seeks to catalogue all known musical settings of works by Rossetti.

The other Rossetti poems set by Coleridge-Taylor in Six Sorrow Songs are “Oh What Comes Over the Sea,” “When I am Dead, My Dearest,” “Oh, Roses for the Flush of Youth,” “Unmindful of the Roses,” and “Too Late for Love.”