This year on August 9, the popular singer and entertainer Whitney Houston would have turned sixty. The month of August also marked the fiftieth anniversary of the birth of hip hop as a genre. This has also been a year during which multiple anniversaries in civil rights history have been commemorated, including the 60th anniversaries of the famous Children’s March in Birmingham, Alabama, of the assassination of the Mississippi NAACP’s first Field Secretary Medgar Evers, of the March on Washington at which Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. delivered his famous “I Have a Dream” speech at the Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, and of the tragic bombing at 16th Street Baptist Church, which took the lives of Addie May Collins, Carole Robertson, Carol Denise McNair, and Cynthia Wesley, leaving Collins’s younger sister Sarah Collins Rudolph as the lone survivor. In November, this nation will also commemorate the sixtieth anniversary of the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, recorded on video by Abraham Zapruder.

W. E. B. DuBois, the preeminent and prolific Black scholar and longtime leader in the NAACP best known as the author of The Souls of Black Folk (1903), which framed “the color line” as “the problem of the twentieth century” and celebrated Black folk culture and its spirituals, passed away in Ghana on the eve of the March on Washington at age 93. As the story goes, at the event, before an audience of 250,000, the gospel singer Mahalia Jackson, one of the few women featured on the program, said, “tell them about the Dream, Martin!” At her urging, Dr. King put his notes aside and concluded his remarks with reflections that helped to make it one of the most celebrated speeches of the twentieth century and a capstone moment of the civil rights era inextricably linked to his national and global iconicity.

It is a testament to this speech’s long and lasting impact that in 1999, at the turn of the millennium, the countdown of the top 100 videos of the twentieth century on Black Entertainment Television (BET) placed the footage of this oratory by Dr. King at the top of its list, indicating in all the promotions leading up to this show that the top choice would not be Michael Jackson’s “Thriller” video (1983), which came in second place.

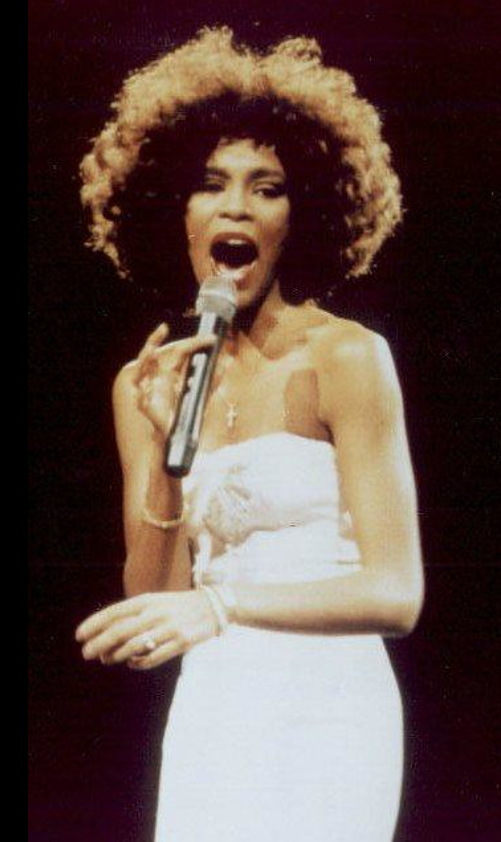

On that day, as Dr. King faced the vast audience surrounding the Lincoln Memorial Reflecting Pool, and shared his dream of a world in which Black children would be judged by the content of their character instead of the color of their skin – including his and his wife Coretta Scott King’s “four little children” – he could scarcely imagine that one of the answers to his prayers had already come in the form of a nearly three-week old baby girl in Newark, New Jersey, whose career and incomparable voice honed in the Black gospel tradition popularized by Jackson would someday lead Whitney Houston to emerge as one of the world’s most talented pop singers, drawing diverse audiences through performances that placed her among the most successful crossover artists of the 1980s. Her iconic performance of the “Star-Spangled Banner” in Tampa, Florida, at Superbowl XXV in 1991 would reach no. 6 on Billboard’s Hot 100, with Houston as a Black woman becoming the first in history to make it a top-ten hit.

I first noticed her beautiful voice and artistry when I saw the videos for some of her earliest songs, such as “You Give Good Love” and “Saving All My Love for You” from her self-titled album Whitney Houston (1985). They were featured on BET shows such as Donnie Simpson’s Video Soul and Alvin Jones’s Video Vibrations, along with the late-night show Midnight Love. These shows were very popular with Black teen audiences during the 1980s for showcasing all of the latest videos by Black artists, including many that mainstream networks on cable television such as MTV and VH1 seldom if ever featured; that is, excepting a few Black musicians who had first made the breakthrough to pop music or come to be classified as “crossover.”

As a ninth grader beginning high school at St. Jude Educational Institute of the City of St. Jude in my hometown, Montgomery, Alabama – best known historically as the final camping place for Selma-to-Montgomery marchers led by Dr. King in 1965 – Houston’s 1985 song “Greatest Love of All” was among the favorites for my classmates and me. This cover of George Benson’s original, “The Greatest Love of All,” which Michael Masser and Linda Creed wrote for the 1977 biopic The Greatest celebrating the iconic boxing champion Muhammad Ali, is a prime example of a cover song that soon eclipsed the success of the original.

In our religion class, from the very first day, our teacher Sr. Peggy Ryan, a young white sister from Chicago new to the Dominican order, urged us to always use “inclusive language.” She referred to us as “freshpeople” instead of using the term “freshmen” (noting that even a great speaker like Dr. King had failed to do so) and had students in the religion sections that she taught decorate buttons that said “IALAC,” which stood for “I am lovable and capable.” Sr. Peggy went on to spearhead school-wide projects such as “Hands Around St. Jude,” in which the entire student body fully encircled our school building and held hands around it, mirroring the popular “Hands Across America” that positioned people to momentarily join hands from coast to coast.

She also led the Liturgy Club of which I was a member, which was responsible for planning the weekly prayer services around the bronze Jesus statue at the foot of the school’s marble staircase in the school’s lobby during the Advent season. The six-foot statue entitled “The Christ” was cast by Richmond Barthé, an African American sculptor of the Harlem Renaissance and the first African American to have his work represented, along with Jacob Lawrence, at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Houston’s song reinforced and served as an ideal complement to the lessons that my peers and I were being taught in school on a daily basis about Christian love and the importance of self-love and self-acceptance. It helped me to begin internalizing that message on my life’s path at age 14, and deeply inspired me, along with all my friends.

We loved seeing Houston, who seemed to be having the time of her life in videos such as “How Will I Know?” (1985) and “I Wanna Dance with Somebody” (1987). She brought us lots of joy. “I Wanna Dance with Somebody” is also the title of the 2022 biopic directed by Kasi Lemmons with Naomi Ackie portraying Houston.

As I read my teen magazines as a high school student during the late 1980s, I was very impressed to learn that Whitney Houston had made history as one of the first Black girls (Joyce Walker preceded her by a decade) to grace the cover of Seventeen Magazine, which I read monthly, and to learn of her background as a teen model. Indeed, back then, I was astonished to read a poll in another one of my teen magazines, in which their mostly white teen girl audience surveyed said their greatest wish was “To have legs like Whitney Houston’s,” which suggested that her crossover appeal went well beyond music. It was nice and interesting to see her body being embraced in that context by a predominately white readership, even if their stated preference reflected what many viewed as an unhealthy obsession with thinness among teen girls, to the point of developing eating disorders.

Realizing that I had legs closer to Houston’s, reading something like that sounded very bizarre and shocking to me. I thought of Houston’s appearance in a bathing suit on the backside of her first album. Then as now, public dialogues about eating disorders routinely obscured other types of issues, including the distinct ones that I faced. Growing up in a Black culture and community in the post-civil rights South that most valued and validated women with curvy bodies, and as girl with a tall and thin body type, I developed what I refer to as “an eating disorder in reverse” as a teen, in which I’d monitor my calorie intake compulsively and binge on food in an attempt to gain weight, in order to get closer to the Black cultural ideal of curviness.

It took me a long time to come to a place of peace and self-acceptance about the body God gave me, and to feel entirely comfortable and confident in my own skin and fully embrace and love it, but women like Whitney Houston no doubt set the standard and paved the way to those breakthroughs on my path. Some of my role models as a teen girl were “big sisters” from the debutante program in the National Sorority of Phi Delta Kappa’s Xinos. In addition to church, they helped to anchor my social life in Montgomery, along with activities in the Dora Beverly Federated Youth Club. In a way, Houston became yet another kind of “big sister” out in the realm of popular culture, walking a bit ahead and helping to light the way forward.

(To be continued.)

Notes

I dedicate this two-part reflection to Tangla Annette Giles (1971-2004). Among my friends, I believe that Houston had her biggest and best fan in Tangla, who LOVED impersonating the videos for songs such as “How Will I Know” and “I Wanna Dance with Somebody.”

Dr. King was nominated for a Grammy in 1969 for Best Spoken Word Recording for his “I Have a Dream” speech. He was posthumously awarded a Grammy in 1971 in this category for his speech “Why I Oppose the War in Vietnam.” Maurice Wallace analyzes the power of his oratory in a compelling new study, King’s Vibrato: Modernism, Blackness, and the Sonic Life of Martin Luther King Jr. (2022).

The banner photo is by Mark Kettenhofen of Houston performing “Greatest Love of All” on HBO’s Welcome Home Heroes, March 1991, via Commons.

The photograph of Prof. Richardson is by Elbert Powell, Sly’s Professional Photography.

Guest Blogger: Riché Richardson

I am professor of African American literature in the Africana Studies and Research Center at Cornell University. My courses include “The Oprah Book Club and African American Literature” and “Beyoncé Nation.” My Op-Eds have appeared in the New York Times, Public Books and Huffington Post, with interviews that have circulated widely, including on NBC’s Today Show and Nightly News and Al Jazeera. My most recent book is entitled Emancipation’s Daughters: Reimagining Black Femininity and the National Body (2021). I am also a visual artist. My mixed-media appliqué art quilts were exhibited in solo shows at the Rosa Parks Museum in Montgomery in 2008 and 2015, and in several national exhibitions, including “Quilts for Obama” curated by Roland Freeman at the Historical Society of Washington, D.C., in 2009. They are the subject of a chapter in Patricia A. Turner’s Crafted Lives: Stories and Studies of African American Quilters (2009).