Translations have long been classed as either literal or free (“word for word” or “sense by sense”). Anne Dacier formulated a classic statement of this opposition in 1699, contrasting “servile” (literal) translations with those that took liberties. In the introduction to her translation of the Iliad, she argued that in trying to be “scrupulously faithful” to the word while ignoring the spirit of the original, servile translations actually become “very unfaithful.” In contrast, because a free translation aims to save the spirit, “it becomes not just the faithful copy of its original, but a second original in its own right.” To make clear her distinction, she then compared translators to musical performers:

The world is full of musicians who are very learned in their art and sing exactly and rigorously all the notes of the songs they are presented with. They do not make a single mistake since they are cold and lack talent and fail to grasp the spirit in which these songs have been composed. Therefore they can put neither the grace in them, nor the joy that is their soul, as it were. But there are other musicians too, more alert and gifted with a more propitious talent, who sing those songs in the spirit in which they were composed, who safeguard all their beauty and make them appear very different, even though they are the same.

Different, but the same. Theories of translation have long ago moved on to other issues about what it means to take a text from one language and render it in another, but Dacier’s musical analogy speaks to the ways in which a cover song can be understood as a musical translation. One singer or group records their version of an earlier well-known song, interpreting it for their audience.

Translations and cover songs raise many of the same questions: in this case, how do meanings change with gender? The examples below each show change occurring simply because they are voiced by women. Race and vocal timbre also help create new meanings, independently of whatever impact the change in musical styles might be. The number of Black women who chose to cover Beatles songs stands out. Among likely reasons for this is the Beatles’ own recording and performance history: in their first two albums and in performances from 1960-63 they covered Black girl groups, and they toured with Mary Wells (1964) and The Ronettes (1966).

Beatles Covers

In a recent article on ten women singing songs by Bob Dylan, writer Lindsay Zoladz cast Marianne Faithfull, Joan Baez, Nina Simone and several others as translators of Dylan, finding meanings in the songs that he had never imagined. This caught my attention because I’ve been assembling a comparable playlist of Beatles songs covered by women, singers whose careers span the globe and all musical styles.

I’ve been struck by how many of them were young musicians in the early years of their careers, people like Alison Krauss, who was 20 when she performed “I Will” with fiddler Mark O’Connor in 1990, putting an Appalachian cast on Paul’s India-inspired love song; or Amy Winehouse who was 21 when she recorded and filmed her intimate, heated rendition of “All My Loving” for the BBC in 2004. She was then Paul’s age when he had composed it and recorded it in 1963. The Beatles pitched it at their ecstatic audiences of screaming teenagers. Adolescent girls listening to Paul could imagine that his promises to “be true” were sung to them. Winehouse, in contrast, addressed another group altogether – older, more sophisticated. She was the one reassuring her lover that, while away, she’d be faithful. Grown men could understand themselves as her intended audience.

Both Krauss and Winehouse reach the goals Dacier had set for successful translations: they are not just faithful copies, but “second originals in their own right;” they made “them appear very different, even though they are the same.” The playlist that now follows focuses on women who covered a Beatles song on their debut albums. Nine songs appear in chronological order, from 1965 to 1978; the singers range in age from eleven to twenty-six.

Debut Albums

Marianne Faithfull, “I’m a Loser” on Marianne Faithfull (1965) – age 18. The dark second side of this album, having begun with her version of the Rolling Stones’ “As Tears Go By,” closes with this song. Her delivery of “I’m a Loser” differs remarkably little from Lennon’s (the tempo is the same, and back-up voices mark each chorus), and yet because it is a young woman – still a teenager – who calls herself “a loser,” who asks “is it for him or myself that I cry,” the message of the song in the mid-1960s differed markedly. She plays against what has been termed her “aristocratic, virginal” persona (Coates, 189).

P. P. Arnold, “Yesterday” on Kafunta (1968) – age 21. From Los Angeles (Watts), Arnold had moved to London in 1966, seeking a career with the encouragement of Mick Jagger. This album also featured “Eleanor Rigby.” No Beatles song has had more covers than “Yesterday.” According to data on Secondhandsongs.com, between the release of “Yesterday” in August 1965 and Arnold’s album in August 1968, at least 120 other singers had recorded it, a third of them women. Black women singers seized it immediately. By the end of 1966 versions had appeared by Patty LaBelle, Barbara Lewis, Gloria Lynne, Freda Payne, The Supremes, Sarah Vaughan, Mary Wells, and Nancy Wilson. In this cover, aside from obvious gender changes (“I’m not half the girl I used to be”), Arnold’s despairing wail at “why … why … why did he have to go,” her full-throated Gospel sound, and the addition of a Hammond organ obliterate Paul’s pensive musings.

Mary McCaslin, “Help” on Goodnight Everybody (1969) – age 22. A folk singer often compared to Joni Mitchell, she impressed people as sounding like “someone on an old country record.” McCaslin takes John’s frenetic cry for help, and tames it, singing it as a duet with herself, accompanying herself on guitar. The slower tempo and the introspective female voice transform the message and the audience. Instead of desperation, there is insecurity; rather than hopelessness, she communicates a sense that, with your help, she’ll be okay.

Rita Lee, “And I Love Him” on Build Up (1970) – age 22. Reverse-gender versions of “And I Love Her” had previously been sung by Carmen McRae (1964), and then in 1965, separately by Esther Phillips, Lena Horne, Mary Wells, and Connie Francis. A year later Shirley Horn, Melveen Leed, and Nancy Wilson each contributed theirs. There have been many, many more. With this album Rita Lee struck out on her own after having been a member of the psychedelic Brazilian rock band Os mutantes (The Mutants). “And I Love Him” was the only English song on the album. She begins low, with her sultry chest voice backed by a quirky accompaniment. Halfway through she jumps up an octave and belts out the remainder of the song, shifting voices from personal to public, shouting her love, defiantly.

Syreeta Wright, “She’s Leaving Home” on Syreeta (1972) – age 26. Stevie Wonder produced this album during the 18 months he and Syreeta were married. Of the nine tracks, they composed three songs together; Wonder wrote three, Wright one, and they covered two, one by Smokey Robinson, and “She’s Leaving Home.” What Paul sang passively, as an outside observer, Syreeta makes personal, as if she is an ally of the daughter sneaking away. By the time she lets loose on the word “free” (“Stepping outside, she is free”), one wonders if she might actually be singing about herself, narrating her escape in the third person.

Tiffany Darwish, “I Saw Him Standing There” on Tiffany (1976) – age 15. This debut album sold remarkably well, reaching #1 in the U.S. for two weeks. Before Tiffany’s gendered version of “I Saw Her Standing There,” the only other prominent woman to have attempted this song was Mary Wells. I doubt there is another Beatles hit that has attracted covers by fewer women. Critics cited Madonna and Stevie Nicks as influences on this album, but panned this track. Evidently the notion of a teenage girl actively choosing a 17-year-old boy (“Well, my heart went ‘boom’ when I crossed that room and I held his hand in mine”), rather than the reverse, was simply not credible. To judge from the uniformly enthusiastic comments to the YouTube video, today’s listeners strongly disagree.

Randy Crawford, “Don’t Let Me Down” on Everything Must Change (1976) – age 24. Crawford was from Los Angeles (Watts) and active in New York City, where she sang with George Benson and Cannonball Adderley. Lennon described this song as another cry for help. Others, including Paul, have interpreted it as a love song to Yoko, as John’s long-range plea to her to make a success of their relationship. But in Crawford’s powerful reading, the lines “And from the first time that he really done me / Ooh, he done me / he done me good” become sexual, as do the many concluding repeats of “don’t let me down” that fill the last minute, especially with the background murmurs of “ow” and “oh” in the lower of the two vocal tracks (years later Annie Lennox would make it blatant).

Björk, “Fool on the Hill” on Björk (1977) – age 11. Björk may have still been ten when she recorded this song, because the album was released four weeks after she turned eleven. In this case the cover is literally a translation: she sings it in Icelandic as “Álfur Út Úr Hól.” And the music follows The Beatles’ recording religiously, including the flute solos. Understandably, Björk does not consider this to be her debut album.

Siouxsie and the Banshees, “Helter Skelter” on The Scream (1978) – age 21. This, the one cover on their debut album, is an extraordinary post-punk revisioning of Paul’s controversial proto-metal song. From its fade-in, wind-up beginning to its abrupt close, the rhythmic and textural variety of this performance far surpasses the original.

This playlist contains songs from nine of 13 debut albums by young women who covered the Beatles (the others are listed in the notes). Although most women singers who issued an album had done so before turning 26, there is one whose debut as an independent performer did not come until she was 43. Private Dancer (1984) was Tina Turner’s fifth solo album, but the first she issued with Capitol Records after her escape and divorce from Ike Turner. With it she began her new musical life. Turner’s searing cover of “Help” slows the song drastically: the Beatles needed just over two minutes, and Mary McCaslin took almost three. Turner stretches it out over four-and-a-half intense minutes, drawing emotional power from the abusive years she had just survived. The degree to which this translation eclipses the original approaches what Aretha Franklin did to Otis Redding’s “Respect.”

Because Beatles songs are so well known, one might question whether “translation” is the proper analogy for these covers. Most people who listen to a Beatles cover will have already heard and understood the original directly. And yet translation also occurs within, and not simply between, languages. George Steiner defines it broadly: “inside or between languages, human communication equals translation” (Steiner, 47). In that sense, in listening to these cover songs, we perform our own translation of someone else’s translation. Like a bilingual reader of a text and its translation, we assess the new song both on its own merits and in comparison with the original.

These young singers (and their agents and producers) included a Beatles song on their debut albums not merely as a way of declaring their esteem for a song (or a group), but rather, to demonstrate their ability to find new meanings in songs people thought they knew. And more: in the choice of which song to cover and the decisions how to translate the original, singers also constructed their own artistic identities.

Notes

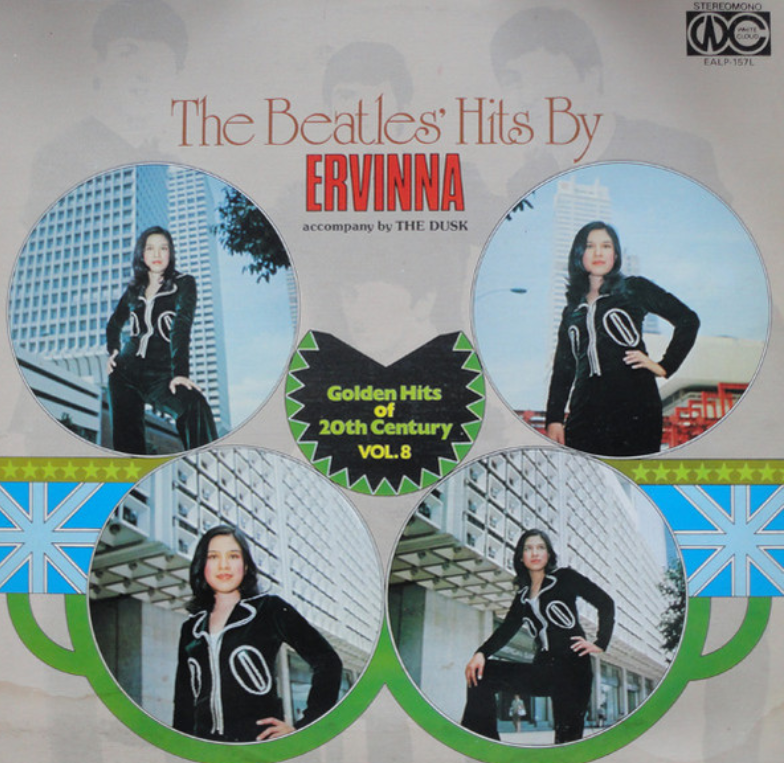

The banner photo is of Indonesian singer Ervinna’s 1976 album, The Beatles Hits by Ervinna. She was 20 years old. This is one of over 200 albums she has recorded.

I have previously published in German about film remakes and rock song reworkings as forms of translation. The English original of this chapter is available on Academia.edu. I also have an earlier essay on Beatles covers.

Other Beatles songs on debut albums: Nancy Sinatra, “Day Tripper” and “Run for your Life” (1966) – 26; Jennifer Warnes, “Here, There and Everywhere” (1968) – 21; Patty Pravo, “And I Love Him” in Italian as “La tua voce” (1970) – 22; Debbie Boone, “From Me to You” (1977) – 21.

Barbara Bradby, “She Told Me What to Say: The Beatles and Girl-Group Discourse,” Popular Music and Society 28/3 (July 2005): 359-390.

Norma Coates, “Whose Tears Go By? Marianne Faithfull at the Dawn and Twilight of Rock Culture,” She’s So Fine: Reflections on Whiteness, Femininity, Adolescence and Class in 1960s Music, ed. Laurie Stras (Farnham: Ashgate, 2010), 183-202.

Anne Dacier, introduction to her translation of the Iliad (1699). From Translation / History / Culture: A Sourcebook, ed. André Lefevere (London and New York: Routledge, 1992).

Christine Feldman-Barrett, A Women’s History of the Beatles (London: Bloomsbury, 2021).

Mary McCaslin had an obituary in the NY Times.

Gabriel Solis, “I Did It My Way: Rock and the Logic of Covers,” Popular Music and Society 33/3 (July 2010): 297-318.

George Steiner, After Babel (New York and London: Oxford University Press, 1975).