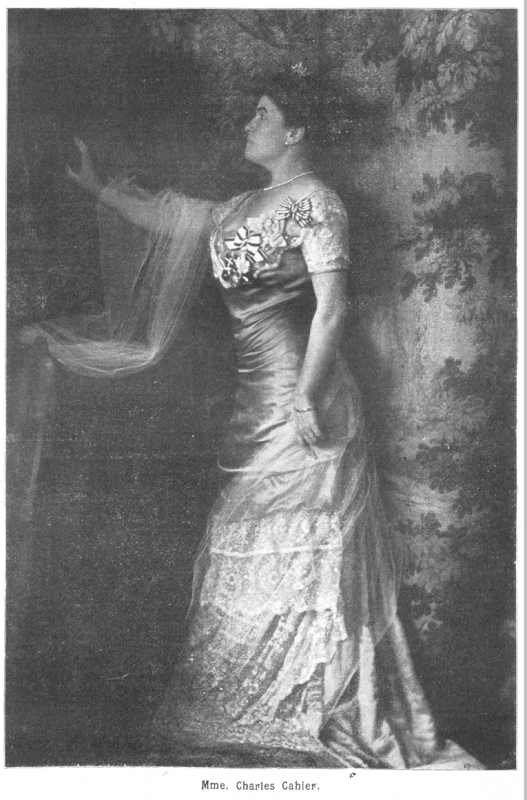

The American singer Sara(h) Cahier (known as Mme. Charles Cahier), one of the most famous contralto singers of her time, is today mainly associated with the premiere of Gustav Mahler’s Das Lied von der Erde in 1911. Indeed, Cahier campaigned tirelessly for this work, which she would sing more than seventy times in her career, linking her name inextricably with the Lied during her lifetime (Wilfing-Albrecht). In addition to her international operatic career, Cahier was a determined promoter of Mahler’s entire artistic output. She also sang the alto parts in the Second and Eighth Symphonies numerous times, including the 1920 Mahler festival in Amsterdam under Willem Mengelberg. But above all, she sang his Lieder, which she included in her repertoire permanently (Stefan, 98).

Since only very few recordings of Cahier exist, the ‘greatest living aria and lieder singer,’ according to Max Kalbeck (Grazer Tagblatt, 8), has largely fallen into oblivion. This might also have been caused by the success of later artists, such as the outstanding Kathleen Ferrier, who had a similar repertoire. Cahier had her breakthrough after being engaged by Mahler at the Vienna Court Opera in March 1907, only shortly before his departure to New York, where she succeeded as Carmen, Fidès, and Dalila. The earliest recordings of her voice date from the same year and include two excerpts from Carmen:

At this time, Cahier was also enjoying great success in the concert hall, which, in addition to her impressive voice, may also have been due to her exceptionally broad repertoire that ranged from the baroque era to contemporary works. In 1928, Cahier also recorded the traditional American spiritual “Swing low sweet chariot” alongside Henry Carey’s “Sally in our Alley.” While most of Cahier’s recordings are of relatively poor quality they give an impression of her remarkable dark timbre and – compared to today’s practice – the particularly strong legato, which she also used in her interpretations of Mahler’s works.

Since Cahier was married to a Swede and during World War I lived and worked mainly in Stockholm, she also showed special interest in contemporary Scandinavian composers, such as Ture Rangström, Toivo Kuula, and Selim Palmgren. She included their songs in her repertoire and sang them as part of her international concert tours. In 1930, she recorded Jean Sibelius’s “Säv, säv, susa,” and Edvard Grieg’s “En svane”:

In the same year Cahier recorded interpretations of the 4th movement “Urlicht” of Mahler’s Second Symphony with the Staatskapelle Berlin under Selmar Meyrowitz as well as of his Lied “Ich bin der Welt abhanden gekommen” (these appear at 5’02” and at 9’46” in the preceding video). She had first sung the Lied publicly – accompanied by one of her longtime companions, Bruno Walter – at several memorial concerts for Mahler as early as 1911.

Mahler’s death in 1911 represented a profound personal and artistic turning point for Cahier. Despite only working a relatively short time with Mahler, their artistic collaboration influenced Cahier’s entire career. She remained an ‘enthusiastic devotee’ of Mahler throughout her life, recalling how ‘this wonderful man retained power over me beyond his death’ (Marilaun, 4). She expressed deep shock over his death and she defended his reputation in a public letter in which she also attacked Mahler’s enemies (“Ein Brief von Madame Cahier,” 2). It was only from this time on, however, that Cahier dared singing Mahler’s music – especially his Lieder – because she had thought that doing so earlier would have seemed like ingratiation, which, she feared, Mahler would have rejected (Marilaun, 4).

In the context of the premiere of Das Lied von der Erde on 21 November 1911 in Munich, various commemorative events for Mahler took place in which Cahier played an active role. On the 15th she gave a piano recital with Bruno Walter in Vienna’s Bösendorfersaal, which she repeated with presumably the same program on the eve of the performance of the Lied in Munich’s Odeon Theatre and again in Vienna in December. In addition to “Ich bin der Welt abhanden gekommen” from the Rückert Lieder, Cahier sang “Um Mitternacht” and “Ich atmet’ einen linden Duft” as well as “Ich ging mit Lust durch einen grünen Wald,” “Das irdische Leben,” “Wer hat dies Liedlein erdacht,” “Hans und Grete,” and “Urlicht” from Des Knaben Wunderhorn.

On the occasion of these concerts, the Viennese press noted that Cahier completely refrained from having the lyrics printed in the concert program, contrary to the usual practice. She believed that reading along with the music was a ‘cheap aid’ that already set the mood for the listeners, which, however, diverted attention from the singer. According to Cahier, the work and its interpretation alone should be decisive for success (“Zum Andenken Gustav Mahlers,” 11).

In the years that followed, Cahier included Mahler’s songs more and more frequently into her program and sang numerous works from Des Knaben Wunderhorn, Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen, and the Rückert Lieder in Vienna alone. Over the years, Bruno Walter, with whom she shared Mahler’s memory and had already worked at the Court Opera, repeatedly accompanied her in these concerts. As early as 1911, the press celebrated the ‘Mahler-Cahier-Walter triad’ and noted that Cahier seemed to sing Mahler’s works with ‘very special love’ (“Die Münchner Gedächtnisfeier für Gustav Mahler,” 2).

Cahier consistently sang Mahler’s music until she reduced her concert activities in the 1930s and returned to the United States before the outbreak of World War 2. She was considered one of the ‘most famous interpreters of [Mahler’s] vocal music’ because of her tireless efforts to popularize his music; indeed, she was essential to the spread of Mahler’s works in the decades after his death (A. S., 28).

Notes

For Cahier’s biography, see: Meike Wilfing-Albrecht, “Cahier, Sarah (Mme. Charles Cahier, geb. Sarah Jane Layton Walker),” Oesterreichisches Musiklexikon online, ed. Barbara Boisits (2022).

Meike Wilfing-Albrecht: “Madame Charles Cahier als Botschafterin von Mahlers Vermächtnis und ihr ‘Monopol’ auf ‘Das Lied von der Erde’,” Nachrichten zur Mahler-Forschung 76 (2023): 62–76.

[Anon.], “Die Münchner Gedächtnisfeier für Gustav Mahler,” Grazer Volksblatt (22 Nov. 1911), 2.

[Anon.], “Ein Brief von Madame Cahier. Von Gustav Mahler und den Wiener Zeitungen,” Neues Wiener Journal (8 Oct. 1911): 2-3.

[Anon.], “Zum Andenken Gustav Mahlers,” Sport und Salon (16 Dec. 1911), 11-12.

Dr. Ernst Decsey, “Graz [Mahler, Das Lied von der Erde],” Der Merker 3/8 (1912): 318.

Grazer Tagblatt (16 Oct.1908), 8.

Carl Marilaun, “Gespräch mit Madame Charles Cahier,” Neues Wiener Journal (23 March 1920): 4.

A. S., “Madame Cahier bleibt ständig in Wien,” Neues Wiener Journal (17 Sept. 1933), 28.

Paul Stefan, Gustav Mahler. Eine Studie über Persönlichkeit und Werk (Munich: R. Piper, 1920), 98. He names Cahier alongside Marya Freund as one of Mahler’s early supporters.

Guest Blogger: Dr. Meike Wilfing-Albrecht

Meike Wilfing-Albrecht earned her doctorate with her dissertation on Egon Wellesz’s operatic aesthetics and has taken part in several projects on Eduard Hanslick. She is currently working for the Complete Edition of the Writings of Arnold Schönberg and also the Johannes Brahms Complete Edition at the Austrian Academy of Sciences, editing a volume of Brahms’s Lieder op. 84-97. Her research interests include the history of musicology, Viennese Modernism, and Gustav Mahler as director of the Vienna Court Opera.