In 1913 women from across America were shocked at the indecent content of many popular songs. In Georgia The Macon News noted that songs “enough to make any pure-minded girl and woman blush” were now “applauded and tolerated” (23 May 1913). Vaudeville singers and the phonograph allowed for widespread promotion of songs that previously had not been performed so “shamelessly and openly, in places frequented by decent people,” noted a Chicago newspaper. Seattle writer Helen Ross warned that the “vulgar effusions” justified as “the latest thing” would have a degrading effect on American youth, writing, “So insidious is the mental poison of these suggestive songs that young people, even people who have been taught to lead clean lives and think pure thoughts, are ignorantly and often unconsciously allowing their natural emotions and youthful ideals to be confused and polluted with the inane, vulgar, and often immoral sentiments which they are constantly hearing expressed in the contagious popular airs of the day.”

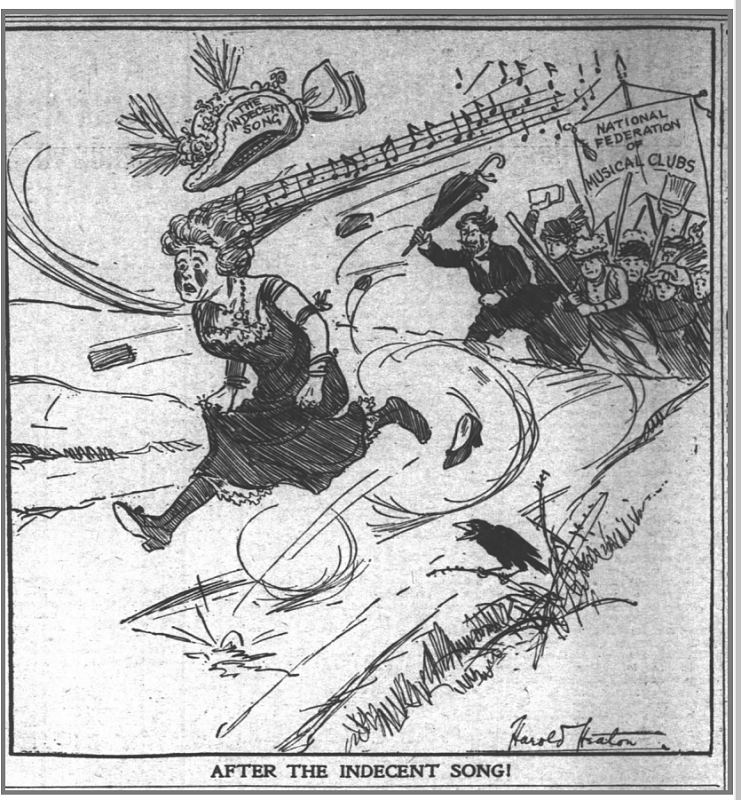

At their Spring 1913 meeting in Chicago, members of the National Federation of Music Clubs (NFMC) acknowledged that something must be done. Its leading figures, such as Rose Fay Thomas, who had originated the idea for the organization twenty years before, declared indecent songs to be harmful and shocking. The famous violinist, Maud Powell, worried that parents were allowing children to bring them into their homes, unaware of the contents of their lyrics. Cartoonist Harold Heaton depicted the Federation, broomsticks in hand, chasing an “indecent song,” portrayed as a woman with short skirts and lacking the respectability of full sleeves. Whether or not obscene, popular song distracted from the National Federation’s goal of promoting classical music in America. Mrs. Jason Walker announced that “We of the committee on American music long have trembled at the trend of the popular song…. We are forced to take action.”

However, the clubwomen of the NFMC were not in agreement about what that action should be. Some members called for the U.S. Postal Service and the Interstate Commerce Commission to exercise the same power over songs as they did over obscene materials sent through the mail or shipped as freight. Other women found the notion of placing embargos on guilty publishers unrealistic. They proposed a national censorship board, perhaps with the Librarian of Congress as censor-in-chief. Constance Barlow-Smith, an Illinois music education professor, pointed out that proper musical instruction for school children could “fight the evil.” Ultimately, the Federation representing well over one hundred thousand members passed a resolution in “earnest protest” condemning “coarse” songs. A copy of the resolution was sent to the mayors of 655 cities requesting their censorship of songs in theaters, cafes, cabarets, and restaurants, any location receiving municipal licensure.

After the meeting, the NFMC’s magazine, The Musial Monitor, reprinted Helen Ross’s article from The Town Crier because it best represented the group’s position. Ross expressed nostalgia for abandoned older songs, such as “Annie Laurie” or “Silver Threads Among the Gold.” Even if they had been overly sentimental, the musical gems of yesteryear did not suggest the immorality of “Love Me While the Lovin’ is Good” or “When I Get You Alone Tonight.” Bright, catchy and tuneful songs with topics like marital infidelity were deleterious, normalizing depravity and leading to immodest dressing, indecent dancing, and eventually, divorce court. Ross stressed the ways in which musical settings could make texts powerful, pointing to patriotic songs from the American Revolution and the Civil War. She claimed that hymns such as “Lead, Kindly Light and “Nearer My God to Thee” had been far more influential for human behavior than rules on statute books.

Ross decried the crimes “committed in the sacred name of music,” arguing that using music for “smut songs” was prostituting it. The lyrics that so scandalized the writer – at least the only ones she dared to print – were from the chorus of a song that had been performed in the Ziegfeld Follies of 1912 that seems only mildly suggestive today.

And then he’d row, row, row,

Way up the river he would row, row, row,

A hug he would give her now and then,

She would tell him when,

He’d fool around and fool around and then they’d kiss again,

And then he’d row, row, row,

A little farther he would row, oh, oh, oh, oh;

Then he’d drop both his oars,

Take a few more encores,

And then he’d row, row, row.

The suggestive power of this song was still strong in 1940. Long before Elvis’s swiveling hips required TV cameras to film him from the waist up, the performance of “Row, Row, Row” by Joy Hodges in the film Ziegfeld Follies of 1912 forced cameras to “aim high.”

In 1920, America’s largest women’s organization, the General Federation of Women’s Clubs, took up the song problem at its Des Moines meeting. Anne Shaw Faulkner Oberndorfer, head of the music division, instigated passage of another resolution condemning the “pernicious influence” of vulgar songs and their “serious menace to the moral and artistic development of the young.” Oberndorfer undertook a highly public campaign, touring the meetings of state federations of women’s clubs around the country. She called for women to pay closer attention to the music heard in their homes, churches, Sunday schools, and movie theaters, warning that they might be horrified at what they would find. Oberndorfer described how a Chicago high school committee discovered that only forty out of two thousand pieces were appropriate for boys and girls to sing together. Under her influence, the General Federation promoted music memory contests so that children would learn European classical music and hymns, thus ensuring their musical safety.

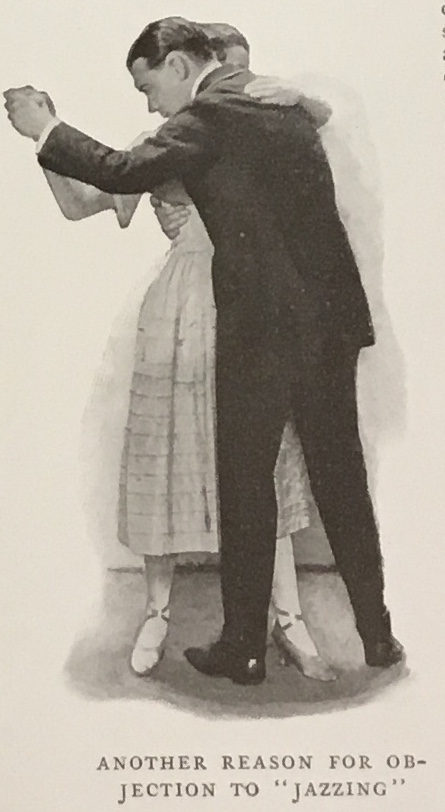

Mrs. Oberndorfer’s crusade quickly turned from song lyrics to a newer and even worse peril, the evils inherent in jazz. Not only did the women of America need to be warned about sexualized lyrics, the new rhythms of jazz were a contagion, stimulating young girls into inappropriate dancing. Oberndorfer’s 1921 article in the Ladies’ Home Journal, “Does Jazz put the Sin in Syncopation?” featured photographs of couples swaying as close together as possible. Swept away by musically unsound rhythms that accented the weak beat, young women were subject to sexual licentiousness, liable to become “neckers” in the arms of their similarly provoked dance partners.

Yet Oberndorfer’s condemnations of jazz made completely clear what was only implied in clubwomens’ concerns about songs: that their objections were based in racist responses to African American musical styles. Oberndorfer and others asserted that jazz was derived from the music of “primitive” and “barbaric” peoples and that the “savage” rhythms of Black music “stimulated brutality and sensuality.” Her rhetoric, following on the heels of the “Red summer” of racial violence in 1919, was designed to fuel prejudice and fear in white women.

Ultimately, publishers did not cower before women’s clubs, “indecent” songs did not disappear, and jazz was not eradicated. In spite of women’s threats, music continues to express human experiences of all types and to reflect changing social norms.

Notes

Thanks to Gillian Rodger for providing insights into the cartoon.

Blair, Karen J. The Torchbearers: Women and Their Amateur Arts Associations in America, 1890–1930. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1994.

Faulkner [Oberndorfer], Anne Shaw. “Does Jazz put the Sin in Syncopation?” The Ladies’ Home Journal 38 (Aug. 1921): 16, 34.

Jerome, William and Jimmie V. Monaco. “Row, Row, Row.” New York: Harry Von Tilzer Music Publishing, 1912. The Lester S. Levy Sheet Music Collection, Johns Hopkins University.

More, Jennifer. “Oberndorfer, Anne Shaw Faulkner.” In Women Building Chicago, 1790-1990: A Biographical Dictionary, 637-38. Ed. Rima Lunin Schultz and Adele Hast. Bloomington: Indiana University, 2001.

Ross, Helen. “The Menace of the Popular Song.” The Musical Monitor and World 4/4 (Dec. 1914): 118-19.