In Part 1 we encountered two groups of women composers, one that wrote many songs to poems by women, and another, conversely, that mostly avoided them. Somewhere in the middle of these two groups are seven of the most successful women composers from the period, three Americans and four Brits who were contemporaries. In this group at least one-third of their published songs set women’s lyrics:

Kate Vannah (USA) – 39 of 88 songs on poems by women (44%)

Margaret Ruthven Lang (USA) – 58 of 133 (44%)

Teresa Del Riego (UK) – 73 of 180 (40.5%)

Amy Beach (USA) – 45 of 112 (40%)

Liza Lehmann (UK) – 126 of 370 (34%)

Florence Aylward (UK) – 45 of 137 (33%)

Guy d’Hardelot (UK/FR) – 45 of 135 (33%)

Remarkably, four of these exceptional women underwent mid-career poetic conversions, each when they were in their forties. Liza Lehmann in 1905, Guy d’Hardelot in 1907, Amy Beach in 1916, and Teresa Del Riego in 1918 – all replaced a decades-long preference for men poets with one for women.

In the case of Lehmann, the comparison is particularly stark, because her shift fell almost exactly in the mid-point of her song production. From 1888 through 1904 she published 165 songs, only 26 of them on women’s poems, not quite 16%. Then from 1905 through her death in 1918, and including songs published posthumously until 1926, another 160 songs appeared, but in these years 100 of them set women’s words, or 62.5%. The spur perhaps came from a new-found confidence in her own poetic voice. After writing the words to just one of her songs before 1905, in that year six of her ten songs used her own poems. The next year brought ten more, two by herself and eight by the feminist and political activist Sarojini Naidu, dubbed the “Nightingale of India” for her poems. The eight Naidu songs represent half of Lehmann’s The Golden Threshold, a sixteen-movement “Indian Song-Garland” – a cantata – for four soloists, choir, and orchestra, all to poems by Naidu.

Here is one of her beautiful Bird Songs, “The Wren” (1907), with words attributed to “A. S.,” or Agnes Smith (the documentation for this identification follows in the notes).

Guy d’Hardelot, the professional name of Helen Rhodes, composed some of the most successful songs of the late Victorian and Edwardian eras. Her tastes in poetry shifted towards women in 1907. From 1889 through 1906 only eight of her 70 songs (11%) had lyrics by women, while from then through 1934, more than half did (33 of 65). The year 1907 was a turning point in her life for other reasons: her fifteen-year-old son, Vivian Guy Rhodes, drowned in May. Whether this tragic event spurred a change in the poets she read, however, I cannot say. Her song, “Three Green Bonnets” (1901), by her favored female poet, Ada Leonora Harris, is in one way uncharacteristic of most of her songs. It lacks the fortissimo operatic conclusion of her biggest hit “Because,” also from 1901, a climax she resorted to so frequently that it became known as the “d’Hardelot ending” (New York Times, 8 Jan. 1936).

Teresa del Riego experienced her transformation in the course of World War I. From 1893 to 1917 she turned to women poets (including herself) for 39 of 118 songs, a respectable 33%. Again, there is a death at the year of transition: her husband F. Graham Leadbitter was killed in action in 1917. From 1918 to 1955 the percentage of women poets jumped to 55%, that is, 34 of 62 songs. Early in her career she wrote the words and music to one of the most popular Edwardian ballads, the quintessential stiff-upper-lip paean, “O Dry Those Tears” (1901), with its admonition, “life is not made for sorrow.” Whether or not she wrote it when she was 15, as claimed, she was just 25 when it appeared to enormous sales of 33,000 copies in its first six weeks. Long a standard for recitals and recordings, it became a staple during the two world wars and at funerals. If Sibelius quoted it in the finale of his Fifth Symphony, composed in 1915, that would be only one sign of how ubiquitous the song was during the war years. Here is Webster Booth’s recording from 1947.

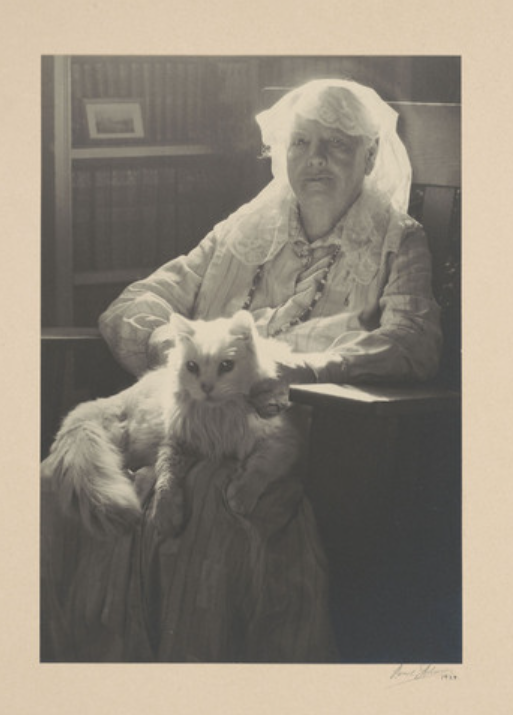

Amy Beach

Of these composers, Amy Beach experienced the most dramatic shift. She had from the beginning shown a greater interest in contemporary female poets than had either Lehmann or d’Hardelot. The three songs she published as op. 1 included texts of Percy Shelley and François-René de Chateaubriand, but also of Kate Vannah, her composer friend and fellow New Englander. In 1894 she was the first of several women composers to recognize the merits of Cora Randall Fabbri, whose tragic death in 1892 came six-and-a-half weeks after she turned 20, and ten days before her poetry collection Lyrics was published. In all, Beach set five of her poems, as did Mildred J. Hill, whose merits as a songwriter have been eclipsed by the ubiquity of “Happy Birthday.”

But in Beach’s first decades of writing songs, she turned primarily to canonical men: Shakespeare, Robert Browning, Victor Hugo, Goethe, Schiller, Heine, and most frequently of all, to Robert Burns for eight songs. A transformation in her desire to set poems by women, almost always women still alive, emerges from this decade-by-decade summary: in the 1880s only one of thirteen published songs set a woman’s poem (not quite 8%); between 1890 and 1909 the percentage increased to 19 of 56 (34%), a respectable balance; through the 1910s, a quieter decade for songs, there were six of 18. Then in the 1920s the balance of men and women flipped dramatically. Fully 14 of her 17 published songs set poems by women (82%); only “In the Twilight” by Longfellow, “Around the Manger” by Robert Davis, and possibly also “On a Hill, Negro Lullaby,” by Anonymous, were not by women. From 1930-41 women wrote five of the nine poems (56%, but if the three anonymous poems were by women, the percentage would obviously be higher).

The pivotal year was 1916, the second of two years spent in California, mostly in San Francisco. The Three Songs, composed that year and then published in 1917, included one poem by Sara Teasdale and two by a new friend, Ina D. Coolbrith. Extraordinarily, before 1916 Beach set poems by women in only 22 of 84 songs (26%), while during her last quarter century of composing, roughly 71% of her songs were on women’s poems, 20 of 28. Excluding the anonymous poems, after 1916 Beach published just five songs with poems by men.

What might have spurred this dramatic change? In the preceding years Beach had of necessity re-invented herself. Upended by the deaths of her husband (June 1910) and her mother (January 1911), she moved to Munich in September 1911, remaining in Germany until the outbreak of war forced her to return in September 1914. After three years without a published song, ten appeared 1914, more than in any other year: one on an anonymous text, two on poems by Abbie Farwell Brown, and seven with lyrics by men. For most of 1915 and 1916, Beach was in California, near close relatives, and her old friend, singer Marcella Craft. In 1916 she settled in San Francisco, near her mother’s sister (Aunt Franc) and her elderly cousin Ethel. And then, precipitously, only months after purchasing a house, she gave it all up and left with her aunt and cousin, moving to New Hampshire (Block, 212).

If her transformation was influenced by an individual, then the most likely candidate is the woman who became a dear friend in San Francisco, poet Ina D. Coolbrith, the “Sappho of the Western Sea.” A beloved figure then in her mid-70s, Coolbrith was in those years President of the Congress of Authors and Journalists. She had recently been named the first-ever Poet Laureate of the State of California. By summer 1916, just as a local newspaper reported Beach at work composing songs to poems by Coolbrith (San Francisco Examiner, 8 Aug. 1916), she wrote a letter to Coolbrith, in which she lamented her upcoming departure from “our beloved San Francisco” (3 Aug. 1916).

But if a new friendship could have triggered her shift, the deeper causes of her new outlook lay elsewhere: in the changed social and challenging financial circumstances of her life as a widow and in her artistic conservatism. She found many faithful supporters in women’s clubs across the country, and in regular residencies in the MacDowell Colony, where among other women she met the poets Katharine Adams and Leonora Speyer, both of whom contributed verses for her songs. With regard to her artistic sensibilities, after 1916, as before, she showed a strong preference for inspirational poetry with a defined meter and lines that rhymed. “The true mission of music is to uplift … To me the greatest function of all creative art is to bring even a little of the eternal into the temporal life” [Beach 1942]. Modernist poetry did not speak to her, either in technique or in message. She turned instead to poets like Coolbrith, whose poem “Meadow-Larks” concludes with a sentiment Beach felt the world needed in 1916 and in the decades to come: “For life is love, the world is love, and love is over all!”

So, once again: did it matter to women who composed songs whether the poems they set were written by a man or a woman? Are there links between the gender of the poet and the style of the composer’s music? The statistics discussed above suggest a partial answer: evidently sometimes. Were there male composers who set a significant number of poems by women? Indeed there were, including some Broadway songwriting teams (e.g., Jerome Kern and Anne Caldwell), but I suspect they were the exceptions. Charles Wakefield Cadman regularly collaborated with Nelle Richmond Eberhart, most successfully on the songs “From the Land of Sky Blue Water” and “At Dawning,” but also on five operas. Samuel Coleridge-Taylor had a penchant for Christina G. Rossetti, as well as Sarojini Naidu, and the American poet Ella Wheeler Wilcox. Arthur Farwell had an unusual predilection for poems of Emily Dickinson. And Cyril Scott set poems by several women, most often Rosamund Marriott Watson. Women at the male-oriented end of the poetic spectrum – Smyth, Chaminade, Clarke and others – had high aspirations as composers of art music; those at the other – Edwards, Jacobs-Bond, Brahe – were ambitious songwriters who aimed to reach broad, primarily middle-class audiences. Education, social standing, generation, and geography all matter.

Possible Factors

In Part 1 of this post I identified two groups of women who differed in how often they set women poets. Group 1 was younger, substantially Midwestern, and much more interested in poems by women; Group 2 was older, substantially British, and more serious in their compositional ambitions. They favored poems by men. In this second post, I took up a related issue, examining four women, three of them British, who experienced mid-career transformations in their desire to write songs with a woman’s voice.

While my thoughts are preliminary, there are several possible factors at play in the national and generational divide, and in the transformations of these four women.

American women’s clubs, which proliferated in the 1890s and flourished for several decades, certainly had an impact. And colleges like Radcliffe, Wellesley, and Swarthmore mounted a student musical every year, in the process training many women musicians, poets and playwrights, not only in their crafts, but in the practice of creating art with other women (at Radcliffe Mabel Daniels composed three operettas). Yet even without the support of such groups and institutions, Liza Lehmann, Teresa del Riego, and Guy d’Hardelot changed. A conservative artistic temperament arguably played a roll. Composers who continued to embrace tonality and avoid dissonance well into the 20th century were more likely to continue setting poetry with meter and rhyme schemes. Composers who sought those traits, and also the uplifting views the poems expressed, evidently turned to women poets with greater than expected frequency.

Paradoxically, turn-of-the-century feminist activism, an international movement, may vie with artistic conservatism in these preferences. The musical trends and transformations I have documented took place just as women were discovering the power of their individual and collective voices, an awakening that took place in tandem with women’s suffrage movements in the UK and US. Women composers and poets often combined their voices, supporting, inspiring, and celebrating each other. More on that in some future post.

Notes

On Beach’s transformation: I’m not the only one to have noticed this shift in the percentages of male and female poets. As I explored what scholars have written about Beach’s songs, I encountered the recent insightful dissertation of Megan Lyons, “Unsung: A Corpus Study on the Art Songs of Amy Beach,” Ph.D. diss. (University of Connecticut, May 2022). Lyons prefers to mark 1910 as the pivotal year and wonders whether the shift might be coincidental.

On Beach’s friendship with Ina Coolbrith, see Adrienne Fried Block’s classic biography of Beach, pp. 212, 214, and 218. Ina D. Coolbrith was called the “Sappho of the Western Sea” in the Oakland Tribune (24 Nov. 1929), the LA Times (4 March 1962), and many other newspapers.

On Liza Lehmann, see Sophie Fuller, “Women Composers During the British Musical Renaissance, 1880-1918,” Ph.D. diss. (King’s College, London, 1998), 210-49.

On the identity of Lehmann’s poet ‘A. S.’: American copyright records from 1907 identify the poet of the Bird Songs as Agnes Smith (Catalog of Copyright Entries. Musical Compositions, Part 3, 2/49-52 (Dec. 1907), pp. 1254, 1276, and 1302-03). And renewal records from 1935 concur (Catalog of Copyright Entries. Renewal Registrations, Music. Third series. Part 5C, 30/3 (1935), p. 165). These records are more persuasive to me than the supposition of Liza Lehmann’s grandson Steuart Bedford that “A. S.” was Alice Sayers, the “faithful nurse” then charged with caring for her two sons; see his notes in the booklet to the CD Liza Lehmann, Collins Classics (The English Song Series, vol. 4) 15082 (1997), 6.

On the date of death of Vivian Guy Rhodes: see Ancestry.com. England & Wales, National Probate Calendar (Index of Wills and Administrations), 1858-1995. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010. Original data: Principal Probate Registry. Calendar of the Grants of Probate and Letters of Administration made in the Probate Registries of the High Court of Justice in England. London.

One who noted the resemblance between Sibelius’s symphony finale and Del Riego’s “O Dry Those Tears,” is W. McNaught, “On Influence and Borrowing,” The Musical Times 90/1272 (1949): 41-45.