In the decades before and after 1900, did it matter to women who composed songs whether the poems they set were written by a man or a woman? Are there links between the gender of the poet and the style of the composer’s music? In other words, did women composers who frequently chose to set women poets differ in their musical styles from those who preferred poetry by men? When, a decade ago, I first began to explore the scholarly potential of my database of women composers from the United States and English-speaking countries who published songs between 1890 and 1930, these questions were far from my mind. Even had they occurred to me then, I probably would have dismissed them.

This two-part post is a demonstration of how much it matters what you count. With regard to what the database could reveal about poets, initially I thought only to identify which poets were most popular for women songwriters, regardless of gender. Ranking poets, by counting the numbers of songs set, was a simple data-sorting task. Then as now, the top ten poets included only one woman, Elizabeth Barrett Browning; but in the intervening years, as the database has continued to expand, the ordering of poets most frequently set by women composers has shifted. Still far out in front, and still completely unexamined, is the British lyricist who changed his name in mid-career from Edward Teschemacher to Edward Lockton because of the virulence of anti-German passions during World War I. So beloved was he by British women composers, that by either name he ranked first among the poets they set:

Lockton (151) and Teschemacher (134), Alfred Tennyson (128),

Frederick Weatherly (125), Heinrich Heine (114), Robert Louis Stevenson (112),

Harold Simpson (107), Robert Browning (101), Clifton Bingham (97),

Elizabeth Barrett Browning (90), Robert Burns (81)

Recently I’ve come to realize that while this ranking is informative, it can obscure a broader appeal by giving undue weight to one composer’s attraction to a particular poet; which means, for example, that Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s elevated standing rests largely on the fixation that Eleanor Everest Freer had for her lyrics. She alone accounts for 47 Barrett Browning songs. Without Freer, Barrett Browning would have been nowhere near the top ten. A more revealing calculation tallies not songs, but the number of composers who set at least one poem by a specific poet. Accordingly, this time counting only women poets, the two most popular with women composers were Christina G. Rossetti (UK), whose poems were set by 53 women, and Sara Teasdale (USA), set by 39 (only two of whom were British). Barrett Browning comes in third, with settings by 36 women, all published before 1918.

Women Setting Women – or Not

A third approach to measuring the relative significance of women poets shifts the focus to the composers to ask: for which women composers were women poets particularly important? And conversely, for whom were they unimportant? To do this I calculated the number of songs women composed to women’s poems as a percentage of their total number of published songs. The results suggest some preliminary answers for the questions posed at the top of this post.

I have excluded from this calculation women who wrote both words and music for all or nearly all of their songs. This stylistically diverse group includes Kathleen Lockhart Manning, Elsa Maxwell, Daisy McGeoch, Ann Ronell, Clare Kummer, and Fleta Jan Brown. Aside from McGeoch, who was British, all were Americans who lived in Manhattan or Los Angeles, and most were involved in musicals or films. This group of poet-composers should also include the prolific Lily Strickland from South Carolina. Of her 291 published songs, 222 are on poems by women, but of those, she wrote the lyrics for 215.

Americans also dominate the group of women who frequently set women poets. Among the top ten, only two had careers in England, but neither was British; one was Canadian, raised in Winnipeg, the other Australian:

Clara Edwards (USA) – 53 of 73 = 73%

Carrie Jacobs-Bond (USA) – 124 of 180 = 69%

Mary Carr Moore (USA) – 47 of 71 = 66%

Laura G. Lemon (CAN/UK) – 35 of 64 = 55%

May Brahe (AUS/UK) – 91 of 168 = 54%

Vaughn De Leath (USA) – 41 of 76 = 54%

Mary Turner Salter (USA) – 72 of 137 = 52.5%

Fay Foster (USA) – 37 of 76 = 49%

Eleanor Everest Freer (USA) – 73 of 148 = 49%

Gertrude Ross (USA) – 17 of 37 = 46%

How different the group of women composers at the other end of the spectrum! Obvious points of difference include geography, generation, and stature as composers of orchestral music and operas. Among those who seldom set poems by women, only three were American, and of those, Clarke and Rogers were born and raised in England (I include Chaminade in my database because of her immense popularity in Great Britain and the United States):

Adela Maddison (UK) – 10 of 47 = 21%

Alicia Adelaide Needham (IRE) – 41 of 211 = 19%

Ethel Smyth (UK) – 4 of 21 = 19%

Rebecca Clarke (UK/USA) – 4 of 26 = 15%

Ellen Wright (UK) – 7 of 50 = 14%

Maude Valerie White (UK) – 26 of 247 = 10.5%

Cecile Chaminade (F) – 15 of 143 = 10%

Hope Temple [Alice Maude Davis] (IRE) – 4 of 47 = 9%

Mabel Wayne (USA) – 11 of 118 = 9%

Clara Kathleen Rogers (UK/USA) – 5 of 58 = 8%

Group Traits

It is not just that the first group was mostly American. They were predominantly Midwestern and Western, with multiple ties to Chicago and California. Clara Edwards left her childhood home in Mankato, Minnesota, for studies in Chicago and then Europe, before finding success in Manhattan. Carrie Jacobs-Bond hailed from Janesville, Wisconsin, then lived in Upper Peninsula Michigan until her husband’s sudden death precipitated her move to Chicago. There, with extensive touring through Iowa, she created her professional identity. In her fifties she moved to Hollywood. Gertrude Ross had a similar trajectory: born in Ohio, raised in Chattanooga, she settled in Los Angeles and then in Hollywood, a mile or so from her friend Carrie. Fay Foster was born in Kansas and educated in Chicago, before studying in Germany, Austria, and Italy. She taught for at least ten years in Pennsylvania. Salter, the oldest of these women, was born in Peoria, IL, in 1856, went to high school in Iowa, and then after marrying, taught voice at Wellesley. Moore grew up in Louisville, KY, and moved to the West Coast at eight, where she became active in San Francisco, Seattle, and Los Angeles. Vaughn De Leath grew up in Illinois and then in Pomona and Riverside, CA, before studying briefly at Mills College. She landed in Manhattan, eventually earning the title of “First Lady of Radio.” And Freer, the lone East Coast native, was born in Philadelphia; after studies there and in Paris, she spent her adult life in Chicago, where, beginning in 1904, she began to publish her songs.

Long after WWI, these women composed tonal music that avoided dissonance, and, excepting De Leath, also the influences of ragtime and jazz. The poems they set conveyed messages of love, comfort, home, and the wonders of nature. Through their long careers, they composed religious songs, songs for and about children, lullabies, love songs, and patriotic ballads.

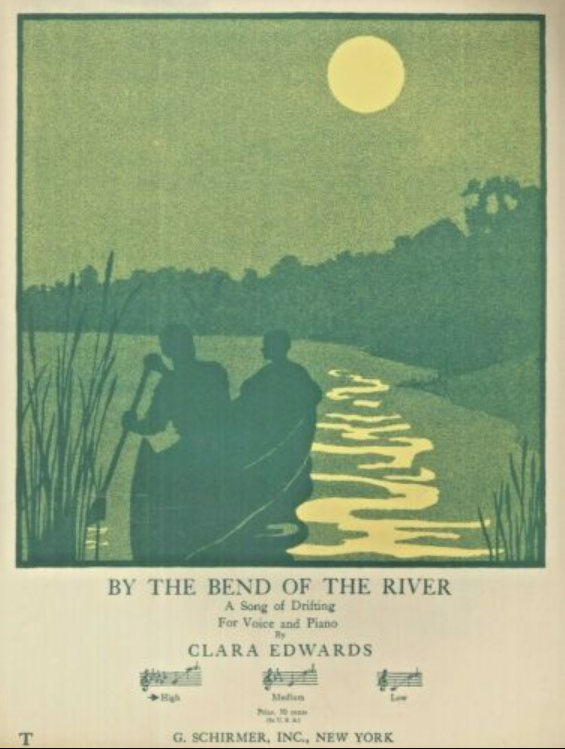

Many of Salter’s songs deal with nature. Four of these, three on poems by women, were recently featured in a Stephen Rodgers’ post on Art Song Augmented, with compelling performances by Camille Ortiz. Some of the most popular songs about “home” include Clara Edwards’s “By the Bend of the River,” which crossed over to become hits for jazz singers such as Betty Carter (1958) and Etta Jones (1962). The poet is identified as “Bernard Haig,” a pen name that Edwards frequently employed. Here is an early recording by Grace Moore (1928).

One of the most often performed songs celebrating home was by May Brahe (pronounced “Brah”). “Bless This House” (1927), composed to a poem by her British friend and collaborator Helen Taylor, was one of 46 songs the two women published together. For decades in the United States this song had a particular association with Thanksgiving Day celebrations. Among the 100+ videos of performances around the world currently available on YouTube, four will suggest the range of occasions at which singers felt this song should be heard: Grace Bumbry at the 1983 Gala of Stars accompanied by James Levine; a rendition that casts the song as a patriotic anthem, by Susan Graham on the steps of the Capital Building at George Bush’s 2005 inauguration (long before, it had been a favorite of Franklin Roosevelt); and a recent amateur choral performance by Glorious Sound, a South African Gospel Choir, at the Playhouse in Durban. Marilyn Horne sang it on Johnny Carson’s Tonight Show, sometime in the late 1970s.

The second, male-oriented group is the more senior. The oldest by a decade is Clara Kathleen Rogers (1844). Five more in this cohort were born in the 1850s (Chaminade, Smyth, Temple, White, and Wright). In contrast, of those who often set women’s verse, only one was born in the 1850s (Salter) and just three in the 1860s (Bond, Freer, and Lemon). Age may have played a role in their poetic preferences, at least in part because the ten to twenty years that separate these two groups meant that the younger women matured in the 1890s and early 1900s, the same decades that women’s clubs proliferated across the United States. From coast to coast, these clubs provided platforms for women community leaders, writers, composers, and performers, creating opportunities for these women to get to know each other’s work.

In the first group, with the exception of Mary Carr Moore, the women composers were primarily songwriters. Moore had ambitions as an operatic and orchestral composer, creating several large works, including an opera in Italian, “David Rizzio” (1937), which was commissioned for a production in Venice (it ultimately fell through), but the others concentrated on songs. In the older group, many of the women were born into upper-class families and studied with illustrious teachers, often in Europe. They aspired to the kinds of musical careers then reserved for men. Hope Temple became Mrs. André Messager, and Maddison was a student, friend, and possibly lover of Gabriel Fauré. Dame Ethel Smyth studied composition with distinguished German teachers and met Brahms, Clara Schumann, and many others. She composed six operas, most notably The Wreckers on a French libretto. Chaminade, of course, was French. Here is Ethel Smyth’s 1913 song, “Possession,” a setting of a poem by Ethel Carnie, one that Carnie had published in her collection Songs of a Factory Girl (1911). Smyth dedicated it to Emmeline Pankhurst.

In Part 2 of this post, I will examine three illustrious composers who, from one year to the next, shifted in mid-career from a preference for male poets to one for females: Liza Lehmann, Guy d’Hardelot, and Amy Beach.

Notes

The banner photo is of May Brahe, ca. 1910. Listen to Episode 7 (26 July 2019) of the Australian podcast, My Marvelous Melbourne, for an informative segment about her life (beginning at 22:35). Presented by Prof. Andy May, it includes an interview from 1975 with her son, Alec Brahe.

See the recently updated version of my database.

For studies of women’s songs in which I make use of my database, see my article “Documenting the Zenith of Women Song Composers: A Database of Songs Published in the United States and the British Commonwealth, ca. 1890-1930;” a follow-up essay from 2015 on the AMS blog Musicology Now; and a WSF post from 2021.

The database figures also in Maren Bagge’s impressive study, Favourite Songs: Populäre englische Musikkultur im langen 19. Jahrhundert (Georg Olms: Hildesheim, Zurich, New York, 2022).