In a fun – if at times obscene – movie from 2017, The Little Hours (dir. Jeff Baena), we are treated to a bawdy, serious, and ridiculous rendering of episodes from Boccaccio’s 14th-century Decameron. The setting is a convent populated by nuns whose behaviors range from mildly acceptable to completely atrocious; it is a celebration of nuns behaving badly. For musicologists and medievalists, what catches the ear is the music – aside from an original soundtrack composed by Dan Romer, the film includes a trecento song by Lorenzo da Firenze and a 16th-century chanson by Clément Janequin. Although not perfectly in tune with the historical moment in an overtly anachronistic film, hearing these songs juxtaposed with the daily lives and shenanigans of young, cloistered women asks us to consider what monastic women sang and listened to. We know they sang the liturgy daily and composed chant thanks to compelling research on female religious communities in the European Middle Ages. But what did they sing and listen to when they weren’t chanting the daily cycle of Office Hours and Masses? When nuns were given musical freedom (or when they took liberties without permission), what music did they sing, how did they have access to it, and what did it sound like?

The musical lives of religious communities outside of the liturgy are often inaccessible to modern eyes (and ears) because non-liturgical music sung in abbeys, convents, and cathedrals wasn’t necessarily written down. At times religious men and women sang and performed secular music that was recorded and connected with lay and aristocratic audiences – the career of “cleric-trouvère” Jean Bodel, for instance, sheds light on the music making of individuals associated with the church but not always concerned with making music for the church. While clerical men who lived and worked in worldly religious contexts could engage in musical practices outside of the church, cloistered communities faced challenges, made more acute for monastic women who faced additional restrictions due to their gender.

But where there is a will, there is a way. Thirteenth-century archbishop of Rouen, Eudes Rigaud, was intimately familiar with the musical and choreographic activities of nuns in his archdiocese taking place in the church and streets, and even with lay participants. The nuns at the priory of Villarceaux, for instance, are cited by Rigaud for dressing up, singing, and leading dances in the streets with each other and with laity. At the Abbey of Montivilliers, Rigaud records musical infractions by nuns who “conducted themselves with too much hilarity and sang scurrilous songs such as drunken farses, conducti, and motets” (O’Sullivan 1964). Resonating with the ribald behaviors depicted in the The Little Hours, Rigaud’s register affords us a glimpse into the (unsanctioned) musical lives of nuns outside of the daily work of the liturgy.

Herrad’s Songs

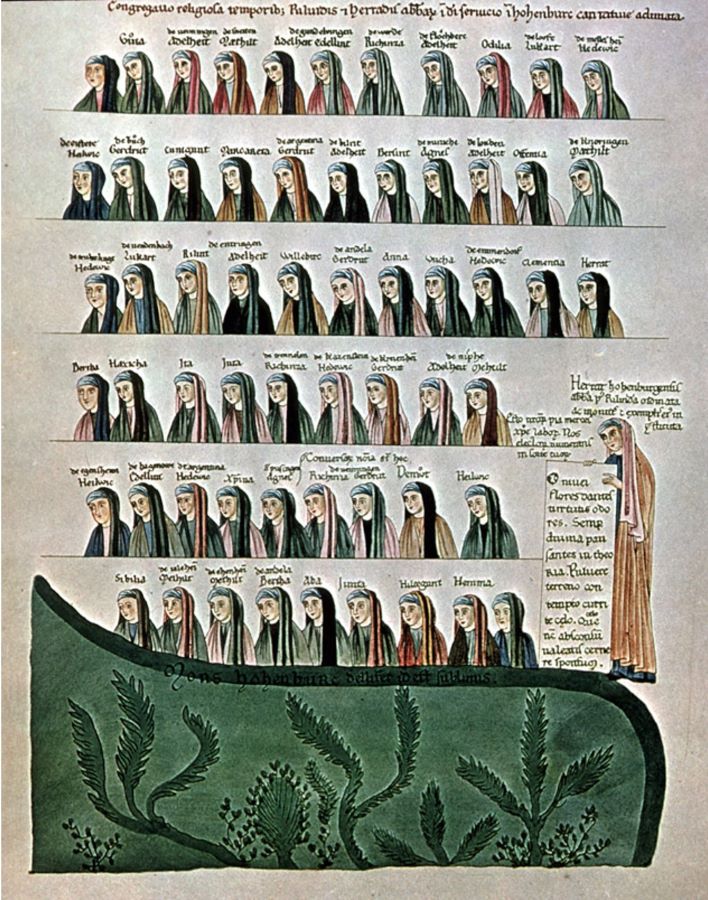

Copied hundreds of kilometers east of Normandy, one particular manuscript includes music that, while not scurrilous, speaks to the quotidian and festive musical practices of nuns: the Hortus Deliciarum, an illuminated, encyclopedic manuscript compiled by Herrad, the 12th-century abbess of the Augustinian monastery at Hohenbourg in Alsace. Destroyed in 1870 during the Siege of Strasbourg, the manuscript survives solely through the material witnesses – notes, drawings, editions – of scholars who had worked with it prior to its destruction. The work of Rosalie B. Green (Princeton Index of Christian Art) in the 1970s led to a reconstruction of the manuscript and partial recovery of the textual, visual, and musical work of a medieval woman and her community. Since its publication, the reconstructed Hortus Deliciarum has become emblematic of the intellectual pursuits of female intellectual communities in medieval Europe. Yet, since it is fragmentary and heavily mediated through 19th-century scholars, the manuscript has long remained at the fringes of musicological research in particular.

Despite its position on the musicological margins, music, and especially song, plays a significant role within Herrad’s intellectual and social project – the abbess recognized the importance of music for the educational as well as social needs of her community of women and provided numerous works for her nuns that range from lighthearted, festive melodies to more serious devotional meditations. Unsurprisingly, Herrad includes songs plucked from other sources, just as her compilation as a whole includes texts from authors writing and copied in major centers like Paris, France, where we likewise find active cultures of Latin song writing and performance. One of the songs Herrad includes is Leta leta concio (fol. 90v), a work likely copied from a source with French origins since it is Latin and French (German is otherwise the only vernacular in the Hortus Deliciarum). The song is connected to Christmas, an occasion for festive music making in social settings when nuns would have been permitted extra freedoms. The poem is simple, repetitive, and joyful, proclaiming “noel” repeatedly and asking the community (“concio”) to rejoice in the holiday (Engelhardt 137):

Leta leta concio

Cinoel

Resonat in tripudio

Cinoel

Hoc in natalitio

Cinoel cinoel noel noel

Cinoel noel noel cinoel

Noel noel noel noel

Noel noel noel noel

Noel noel noel

Cinoel cinoel cinoel cinoel

Noel noel noel noel noel

Although the song was notated according to 19th-century editorial practices, no diplomatic facsimile of the melody exists. What does survive is an all-Latin, notated rendering of the song in a mid-13th-century Parisian manuscript likely associated with male clerics at Notre Dame Cathedral, now in the Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana as Pluteo 29.1, fol. 470v:

Leto leta concio

Hac die

Resonet tripudio

Gratie

Hoc in natalitio

Vox sonet

Ortum dat rex glorie

Venie.

Leto leta…

Rather than the “cinoel” and “noel” of the Hortus deliciarum, in the Florence manuscript we have syllabically identical Latin words and short phrases like “this day” and “goodwill” inserted in between Latin lines shared between the two songs. Thanks to the notation in this later source, the early music ensemble Discantus, directed by Brigitte Lesne, was able to adapt the version in Herrad’s manuscript to this later melody (some scholars have posited for a number of reasons that the song in the later Parisian source was to be performed as a canon, as is done in this performance):

This song, and others in the Hortus Deliciarum are not exactly the scurrilous songs Rigaud frowned upon in abbeys in his archdiocese, but neither are the songs part of the opus dei of Hohenbourg Abbey. Instead, Herrad provided poetry and music for her nuns that wasn’t exclusively serious and pedagogical (which might be expected considering the intellectual and pedagogical work of her encyclopedic compendium).

She chose music that was lighthearted, festive, easy and enjoyable to sing, music – like contemporary Christmas carols – that fulfilled the desire of monastic women for musical entertainment. In this case, access was provided by Herrad herself, made possible because of her ability to source texts (musical and otherwise) from across Europe and bring them into her cloistered community through the compilation of the Hortus Deliciarum. While the social environment she was shaping in the Abbey is nowhere near that depicted in The Little Hours, Herrad nevertheless recognized that music was integral to the social and communal lives of monastic women. And while we might wonder at what songs the nuns of Hohenbourg Abbey sang when Herrad wasn’t listening, we can at least begin to listen in on what Herrad herself envisioned for the varied musical landscape of this community of religious women.

Further Reading and Listening

Read more about medieval Latin song in my book, Devotional Refrains in Medieval Latin Song (Cambridge University Press, 2022), including others copied in Herrad’s Hortus Deliciarum.

Boynton, Susan. “Women’s Performance of the Lyric Before 1500.” In Medieval Woman’s Song: Cross-Cultural Approaches, ed. Anne L. Klinck and Ann Marie Rasmussen, 47-65. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2002.

Discantus (dir. Brigitte Lesne). Hortus deliciarum: Hildegard von Bingen, Herrad von Landsberg, 12th Century. Paris: Opus 111, 1998. CD.

Engelhardt, Christian Moritz. Herrad von Landsperg, Aebtissin zu Hohenburg, oder St. Odilien, im Elsass, in zwölften Jahrhundert und ihr Werk: Hortus deliciarum. Stuttgart and Tübingen: J. G. Cotta, 1818.

Grau, Anna Kathryn, and Lisa Colton, eds. Female-Voice Song and Women’s Musical Agency in the Middle Ages. Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2022.

Green, Rosalie, ed., Herrad of Hohenbourg: Hortus deliciarum. 2 vols. London and Leiden: Warburg Institute and Brill, 1979.

Griffiths, Fiona J. The Garden of Delights: Reform and Renaissance for Women in the Twelfth Century. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2007.

O’Sullivan, Jeremiah F., ed. The Register of Eudes of Rouen. Translated by Sydney M. Brown. New York: Columbia University Press, 1964.

Schotter, Anne Howland. “Woman’s Song in Medieval Latin.” In Vox Feminae: Studies in Medieval Woman’s Songs, ed. John F. Plummer Studies in Medieval Culture, 19-33. Kalamazoo: Medieval Institute Publications, 1981.

Yardley, Anne Bagnall. Performing Piety: Musical Culture in Medieval English Nunneries. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006.

Guest Blogger: Mary Caldwell

I am an assistant professor of music at the University of Pennsylvania, and author of Devotional Refrains in Medieval Latin Song (2022) as well as book chapters and articles published in the Journal of the Americam Musicological Society, Journal of Musicology, Journal of the Royal Musical Association, Music and Letters, Plainsong & Medieval Music, and others. I write on song and refrain, ritual and mysticism, citation and intertextuality, language, and pedagogy, and my current research engages with studies of gender and sexuality, critical hagiography, and dance.