When we think of Clara Schumann’s songs, the contexts that often come to mind are private, even deeply intimate. Robert and Clara Schumann themselves, for example, exchanged song manuscripts and dedications as gifts. In this post I will explore a complementary side of Clara Schumann’s Lieder: how she used them to publicly present her artistry as a virtuoso pianist-composer.

I recently published a book, Becoming Clara Schumann, about Schumann’s concert career, and my favorite part of the research process was trawling the complete run of her programs archived at the Robert Schumann Haus in Zwickau. Program by program, I could follow Schumann on tour, watching her establish her signature repertoire, adapt to different musical ecosystems, and evolve alongside her musical world. I always paid special attention when she performed her own compositions, and songs were some of the original works she programmed most often. Thinking about her songs as public performance vehicles gave me a new perspective as I – a decent pianist though only marginally competent vocalist! – played through the scores.

Schumann’s concerts, like those of many nineteenth-century virtuosos, were variety shows that treated audiences to a range of genres, styles, and performers. She performed as a soloist but almost always brought collaborators onstage – internationally or locally renowned musicians who would add appeal to her concerts. These included fellow pianists for duets, string players for chamber music, and vocalists for sets of songs.

Schumann’s song sets occasionally included her own Lieder set alongside music by (usually male) contemporaries and forbears. She often wrote about the joy and pride she took in composing, and she evidently found it fulfilling to put her work before the public. But these performances also likely served a more strategic purpose: to inspire audience members to purchase the sheet music of these compositions.

To take one example, at her 31 March 1841 concert at the Leipzig Gewandhaus, Clara Schumann featured some of her go-to virtuoso showstoppers (including the second and third movements from Chopin’s Piano Concerto No. 2) while also using her star power to promote her new husband’s recent compositions: his Symphony No. 1, the seventh of his Novelettes, and two songs from Myrthen (“Die Lotosblume” and “Der Nussbaum”). Between the Myrthen selections, Clara promoted her own forthcoming work: she accompanied her “Am Strande,” which would appear in print that July. Although on this occasion Clara only briefly took the stage as a composer, the roiling accompaniment and intensely theatrical vocal line in “Am Strande” surely made a splash when performed between Robert’s two soft-spoken songs. Wilhelm Gerhard’s poem “Am Strande,” was soon translated by Robert Burns as “On the Shore.”

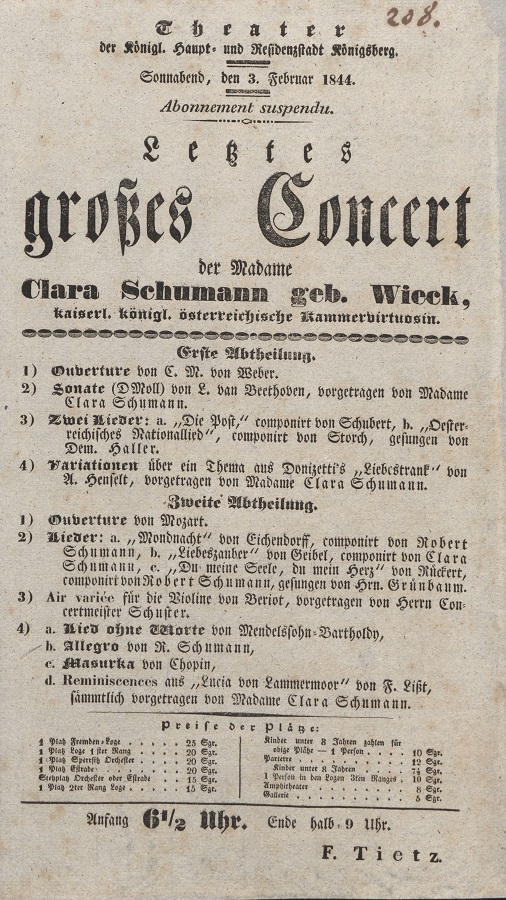

When the Schumanns went on their 1844-45 Russian tour, Clara promoted their recent Lieder publications. In Königsberg on 3 Feb., for example, her song set included not only Robert’s “Mondnacht” and “Widmung” but also “Liebeszauber” from her own Sechs Lieder, Op. 13, published only a couple months prior (program pictured above).

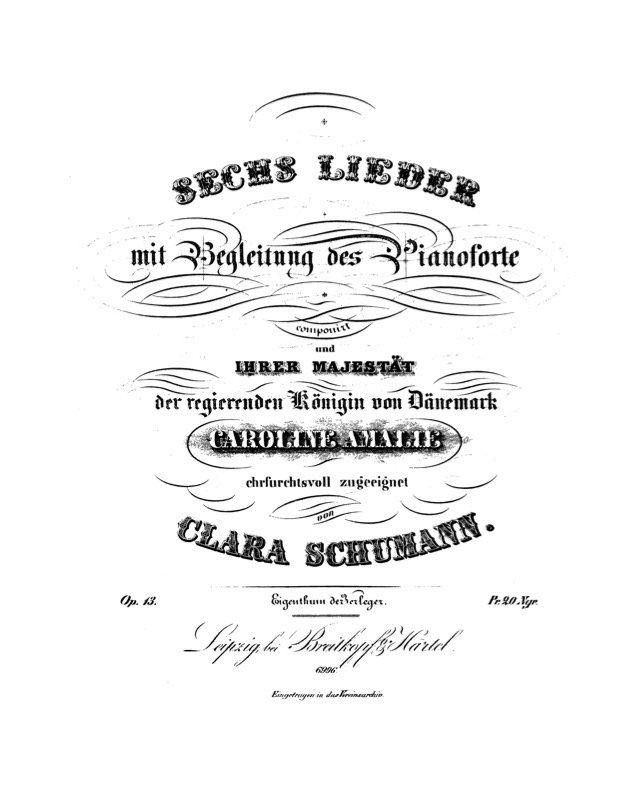

Promoted from the stage, Clara Schumann’s Lieder also went public by entering piano-owning households. Schumann’s status as a celebrated, continent-trotting pianist ensured that her songs would grab attention. Prominent music journals gave reviews of her Op. 13 front-page billing, recognizing them as newsworthy events. One critic reminded readers of Schumann’s fame and technical wizardry while assuring them that the songs were well suited to Lieder enthusiasts’ tastes: “The renowned virtuoso offers friends of song a truly welcome gift,” he wrote, praising the songs’ “thoughtful seriousness.” The dedication on the front page of Op. 13 to Queen Caroline Amelie of Denmark nods to Schumann’s renown: she had just visited the queen’s court during a series of concerts in Copenhagen.

As I explored these songs, one feature that struck me again and again was how they showcased Schumann’s richly detailed, thoughtful approach to piano texture. Careful attention to sonority was one of her hallmarks as a performer. In 1832, for example, Robert praised her approach to voicing and balance: she achieved a texture in which “the bass lines should be the sustaining roots, translucently overhung but not concealed by the other voices.” Decades later, Franz Liszt observed that she spent extraordinary time before her concerts testing pianos, observing the subtleties and potential pitfalls of instrument and hall. Schumann refined this awareness through decades of playing pianos of different makes, witnessing cutting-edge approaches to virtuosity, and composing her own works. For those who played and sang her songs, they offered a chance to let the virtuoso guide their fingers and voices, conjuring complex, changing webs of sound from instrument and body.

“Warum willst du and’re fragen,” one of the songs Schumann programmed most frequently, packages this reward in deceptively simple guise. The speaker in Rückert’s poem urges their beloved to look nowhere but their eyes for proof of love. Schumann not only draws us into the text with an artful series of evaded resolutions. A subtle change of color also happens whenever the speaker directs their beloved’s gaze into their truth-telling eyes. The deep, flowing arpeggios halt, and instead the pianist shadows the vocalist’s rhythms with chords in a higher tessitura. Meanwhile, the vocalist turns from gently arching melodic lines to declaim on one note and climb to a melodic peak. Depending on their approaches, performers can turn these passages into moments that mix vulnerability and fervor in various proportions: time slows and the sound thins and brightens as the speaker reveals how they really feel.

Equally detailed plays of texture abound in Schumann’s songs. In the athletic “Liebeszauber,” for example, she selectively thins and builds up the pianist’s pulsating chords, creating full-fisted sonorities and soaring vocal high notes at the song’s climax but burying the repeated notes in a middle voice and letting the voice sink to a murmur for the wistful final verse. In “Geheimes Flüstern,” by contrast, she uses a multilayered texture to script moments of tension and exchange between collaborators. At the opening words, “Mysterious whispers, here and there,” pianist and vocalist trace the same melody, but their implied meters gently grate against one another. The song is in 3/8, but in the introduction the pianist imposes a duple division on the measure, one that continues even as the vocalist enters in a clear triple meter. Here and in similar passages, the doubled but out-of-phase melodies create a flurry of echoes, so that players might feel surrounded by quiet reverberations, even briefly disoriented in the presence of their own metrically distorted reflections.

For her concert audiences and for those of us who are friends of song today – playing in public or private – Schumann’s Lieder provide an opportunity not just to appreciate her mastery of this genre’s aesthetic of literary sensitivity; they also let us experience aurally and even bodily Schumann’s creative engagement with the instrument at the heart of her musical life and career.

Notes

The banner photo is a detail from Adolph von Menzel’s watercolor of Clara Schumann and Joseph Joachim playing music.

Suggested further listening:

The Songs of Clara Schumann. Susan Gritton, soprano; Stephan Loges, baritone; Eugene Asti, piano. Hyperion, 2007.

Or, for a recording that showcases Clara Schumann’s approach to the piano in genres other than song (from chamber music, to her concerto, to solos flashy and lyrical), check out Isata Kanneh-Mason, Romance: The Piano Music of Clara Schumann. Decca, 2019.

Suggested further reading:

Nancy B. Reich, Clara Schumann: The Artist and the Woman. Revised Edition. Cornell University Press, 2001.

Various authors, ed. Joe Davies. Clara Schumann Studies. Cambridge University Press, 2022.

Guest Blogger: Alexander Stefaniak

Alexander Stefaniak is an Associate Professor of Musicology at Washington University in St. Louis, and his research focuses on 19th-century piano music, performance, and virtuosity. His recent book Becoming Clara Schumann (Indiana University Press, 2021) explores how she strategically developed her career within the evolving culture of “classical music.” Prof. Stefaniak also authored Schumann’s Virtuosity: Criticism, Composition, and Performance in Nineteenth-Century Germany (Indiana University Press, 2016).