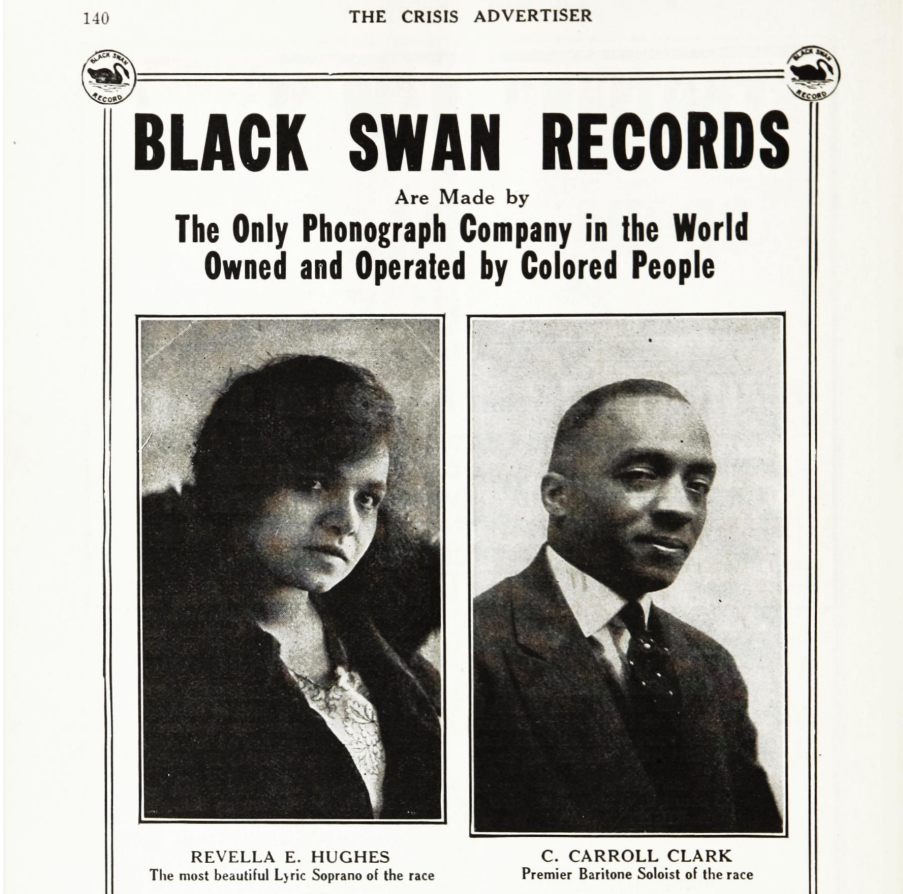

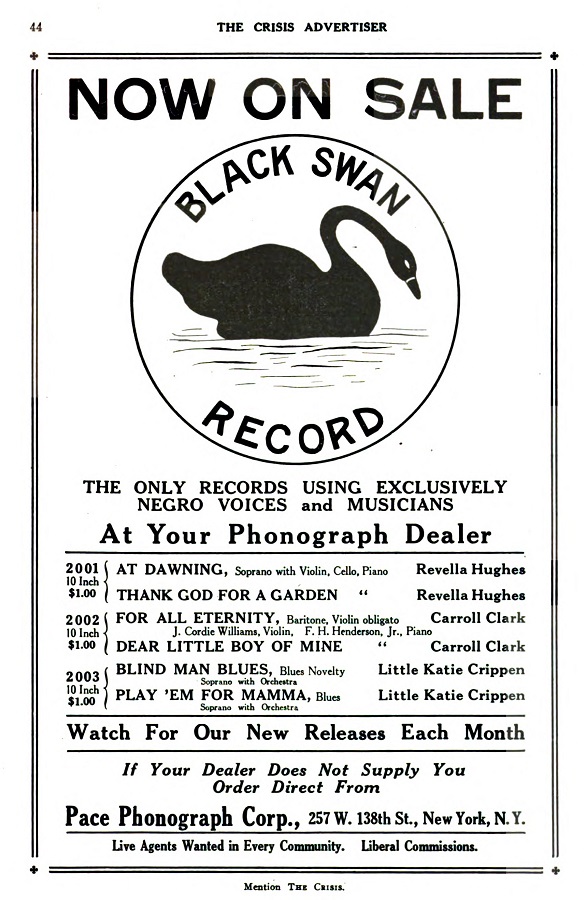

With an ambitious promise to “record popular songs of the day, dance melodies, blues, high class ballads, sacred songs, Spirituals and operatic selections,” Harry Pace launched New York–based Black Swan Records in May 1921, committed to making “the only records using exclusively Negro voices and musicians.” As an African American–owned record company the label was preceded only by George Broome’s much smaller-scaled Broome Special Phonograph Records in Medford, Massachusetts, active 1919–1920.

Two of Black Swan’s initial three releases are telling. Its very first record featured soprano Revella Hughes with a piano trio, basking in parlor song reverie on Charles Wakefield Cadman’s “At Dawning” and English composer Teresa Del Riego’s “Thank God for a Garden.” On its third, Katie Crippen delivered the latest blues: “Blind Man Blues” backed with “Sing ’Em for Mamma, Play ’Em for Me.” In the latter (linked below), toward the end of the first chorus, Crippen sings:

Don’t play it so fast / It has lots of class

But that ain’t all / It’s full of jazz

The conjunction of jazz and class was emblematic of Pace’s strategic vision. Pace was certainly not squeamish about popular music – he was, after all, a former partner of W. C. Handy at the pioneering Pace & Handy publishing company, which specialized in Black pop – though at Black Swan, stylistic diversity was a means, not an end. In a July 1921 address to the classical music–leaning National Association of Negro Musicians, Pace laid out Black Swan’s battle plan: “We have issued twelve records, six of the standard type, three popular type and three ‘blues.’ We have had to give the people what many of them wanted in order to get them to buy what we wanted them to want.” By “standard” Pace meant ballads of the sort that Hughes recorded and arranged spirituals, his hope being that these sides, along with releases by Black classical musicians, would broaden African American music consumption patterns. The long game was clear: Come for the pop and blues, stay for the high-class stuff.

The Hughes and Crippen records also indicate how central women’s voices were at Black Swan, which folded in 1923. We might characterize the majority of the women who recorded for the label as part of the Plessy generation: born in the 1890s and coming of age during the “nadir of race relations,” yet entering adulthood at a watershed moment for Black musicians as phonograph artists. Black Swan’s extensive blues catalogue – much of it recorded with piano or band accompaniment by its musical director Fletcher Henderson – rode the early-Twenties wave of live and recorded performances of “classic blues” by Black woman vocalists. It is probably more accurate to say that many of these singers were experienced vaudeville and nightclub artists who, because of the current vogue, increasingly featured blues as part of their act.

Black Swan Voices

Black Swan’s roster of women’s voices reflects the range and fluidity of the

A decade older than these relative up-and-comers was Essie Whitman (1882–1963), a member of the famous Whitman Sisters who was already forty when she recorded “If You Don’t Believe I Love You” with a mature chest voice that sounds kindred to Ma Rainey or Sophie Tucker. These voices may have shared the vaudeville circuit, but their individuality and versatility were tools of the trade. “I was a cabaret artist in those days,” Hegamin recalled, “and I sang everything from blues to popular songs, in a jazz style.”

Other women’s voices helped further Pace’s aim of exhibiting and extending the continuum of Black musical tastes. Popular song stylists like Inez Richardson (n.d.), sounds like the consummate pro singing “Love Will Find a Way” from Noble Sissle and Eubie Blake’s landmark musical Shuffle Along (1921); she, and Bessie Allison Buchanan (1902-80), the Cotton Club chorus girl who went on to become the first African American woman elected to the New York State Legislature, offered voices recognizably apart from the blues. Marianna Johnson, like her good friend Revella Hughes, was a committed member of the Marcus Garvey movement, which eventually led to a falling out with Pace, though not before she recorded a pair of sentimental ballads, “The Rosary” and “Sorter Miss You.”

Classically Trained Women

Pace, a W. E. B. Du Bois protégé, was determined that the voices of classically-trained Black singers, who were systematically denied the opportunity to record, would be documented for posterity. In some cases, these singers performed crossover repertory, like Nettie Moore who recorded “Deep River” and “Song of India,” adapted from Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov’s opera Sadko. During her 1921 European tour with the Southern Syncopated Orchestra, soprano Hattie King Reavis (1890–1970) was praised by critics for the “exquisitely rendered” R. Nathaniel Dett anthem “Listen to the Lambs.” Upon her return, Black Swan recorded Reavis’s authoritative performance of the Dett-arranged spiritual “I’m So Glad Trouble Don’t Last Always.”

Two Detroit natives, Antoinette Garnes (c. 1887–1938) and Florence Cole Talbert (1890–1961), both graduates of Chicago Musical College, were Black Swan’s most experienced performers of operatic repertory. A Black Swan ad promoted Garnes as “the only colored member of the Chicago Grand Opera Company” when the label released her two recordings, which included impressive coloratura on “Caro nome” from Giuseppe Verdi’s Rigoletto. Talbert built a national reputation in the nineteen-teens concertizing across the U.S. and was a pioneering Black Aida, singing the role in Italy in 1927. Among the soprano arias she recorded for Black Swan were “The Bell Song” from Léo Delibes’s Lakmé and the venerable Irish song “The Last Rose of Summer,” popularly known, among other places, from Friedrich von Flotow’s comic opera Martha. (Talbert’s 1919 recording of “Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen” was featured in an earlier post.)

It could be that Black Swan simply collapsed under the weight of its multiple agendas, among them fostering “buy Black” race pride, building an audience for Black classical artists, tapping while shaping Black consumer taste, and running a successful business in a music industry deeply invested in its failure. But Pace’s most important endeavor may have been his demand that we listen. “Buy Black Swan Records and you will help preserve the best voices of the race.” So read the label’s introductory advertisement in The

Note

The banner photo is taken from a full-page ad in The Crisis, v. 22/3 (July 1921).