This past Sunday, the iconic Soviet and Russian singer Alla Pugacheva made news for a post on Instagram protesting the unprovoked Russian invasion of Ukraine. She asked to be added to the list of “foreign agents” who have named and shamed Russia for its aggression, rejecting the war as a spetsoperatsiya, a special operation meant to liberate Ukraine from Nazism, NATO, and American interference. One person on that list is her husband, a television personality and comedian who has also condemned Vladimir Putin’s actions. The couple briefly hosted a talent show called “Two Stars” (Dve zvezdy), the Russian equivalent of VH1’s “But Can They Sing?”

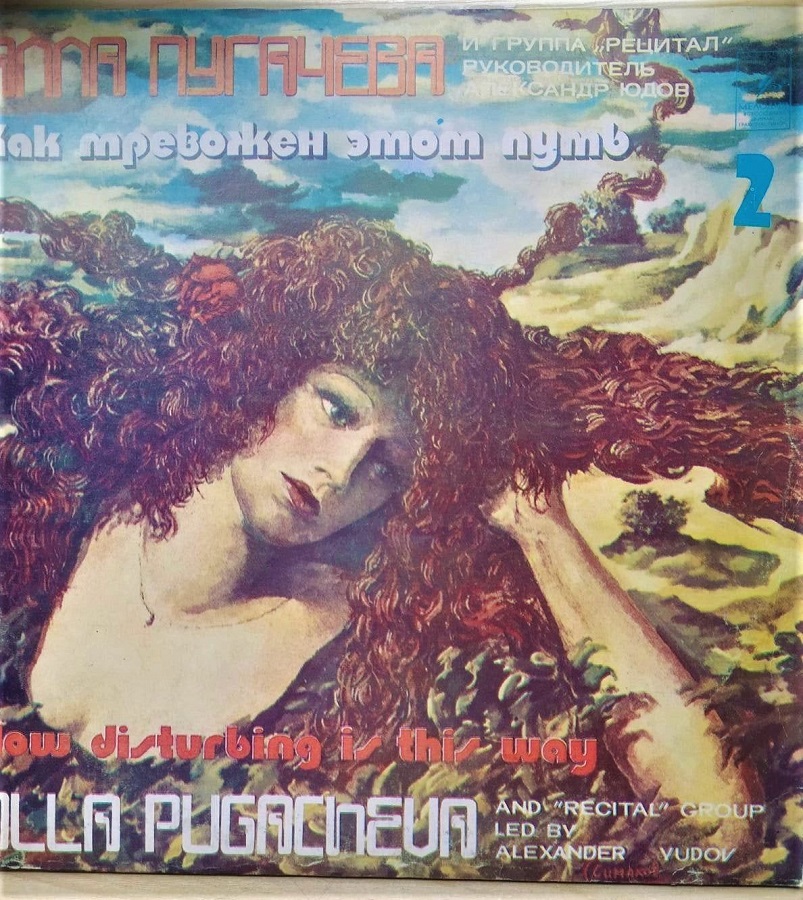

At 73, Pugacheva has been a public figure in Russia for half a century, having built her career as a star of Soviet disco, television variety shows, and cinema. As a child, she studied music in Moscow, but her earliest and most important musical education came from her parents, whose dreams of the circus and the concert stage were thwarted in their youths: Alla’s father lost his right eye to crossfire when he was in the Red Army; her mother performed for the troops during the Second World War, but overtaxed her voice, sacrificing its range. Alla grew up listening to Edith Piaf and Ella Fitzgerald, hammed it up in school, sang on a radio morning show, joined a circus then a light music ensemble called New Electron (Noviy Elektron). She briefly taught, but her flamboyance alienated the glowering, gray-suited bureaucrats minding the curriculum. After winning a prestigious Eastern European song contest held in Bulgaria named Golden Orpheus, she studied acting at GITIS, the Russian Institute of Theater Arts. Her reworking of a song called “Harlequin” (Arlekino) ties her experiences together. David MacFayden, author of a book about Soviet popular music, quotes her description of “a circus-like spectacle, a song that allowed me to fill myself with both pain and mockery, both irony and sadness.” The music video is shot in one of Moscow’s metro stations, a theatrical but mundane space:

She’s famous for her musical contribution to the movie The Irony of Fate (Ironiya

Pugacheva is also famous for another New Year’s song, “Million Scarlet Roses” (Million alykh roz), first heard on television in 1983 before becoming a massive seller on vinyl. She’s never much liked the song, but it’s an ever-favorite singalong, mildly tongue-twisting, with a bubbly, bouncy synthesized Soviet champagne accompaniment. The tune was originally Latvian, based on a tale about an artist so in love with an actress that he sends a cart overladen with flowers to her hotel. The title words are repeated hypnotically. It’s limpid, pearly music that people are embarrassed to say they love but love nonetheless.

She’s not averse to power ballads, replete with guitar solos that seek to enact their own transcendence, escaping the predictable structures of popular song. “Planes, Departing” (Samolety uletayut) showcases the qualities that made Pugacheva a star: she performed her personality in an era and civic space devoid of personality and in so doing imagined stardom in a place ideologically inhospitable to fame. She embodied, glasnost’ (openness) before the term became Mikhail Gorbachev’s governing policy and part of the Soviet Union’s undoing. (Gorbachev admired her, as did Yeltsin and, until now, Putin too.)

Pugacheva has won major awards in Russia, used her profile to raise awareness of and funds for the victims of the Chernobyl nuclear disaster, performed internationally, branded a perfume, graced magazine covers, and became exceedingly well-to-do. Her celebrity came, remarkably, from her demands for autonomy – her freedom. It must gall her, thirty years after the collapse of the Soviet Union, to have to keep demanding it.

In 2019, Russian director Kirill Serebrennikov mounted a production at the Gogol Center in Moscow called “Our Alla,” a tribute to Pugacheva and the height of her fame during the Soviet era. The production included reworked versions of her songs with nods to other divas like Lady Gaga and British (not Soviet) synthpop. Pugacheva herself attended the show, fabulously attired and just as red-headed and gap-toothed as she was as a kid. Serebrennikov, another artist at serious odds with the current regime, admires Pugacheva’s fearlessness, permissiveness, and irrepressible optimism.

Pugacheva may have stepped out of line with the regime in criticizing the Russian invasion of Ukraine, but she has always been in step with the times. In 1999, when the Gay Men’s Chorus of Los Angeles traveled to Russia, she joined them onstage for a performance of “We Shall Overcome.”

Guest Blogger: Simon Morrison

I teach at Princeton University, and I write about Russian music, ballet, and Stevie Nicks.