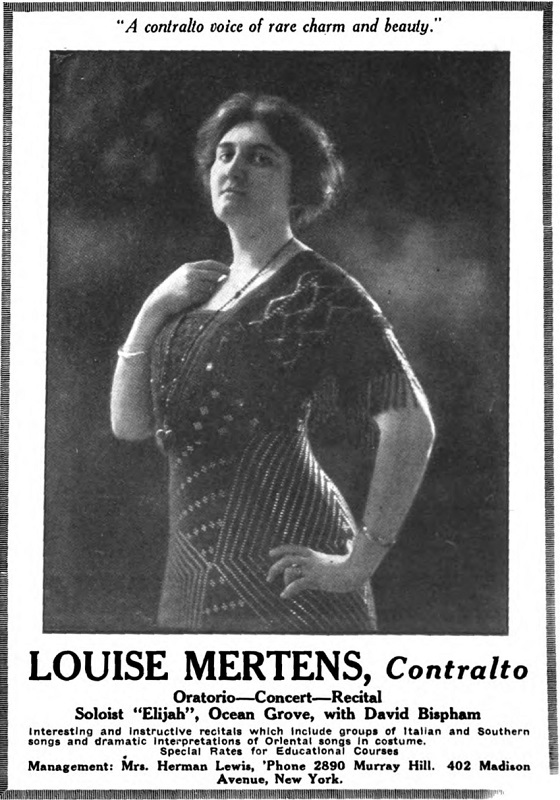

“Feminism in music is to receive a practical exemplification next season,” declared Musical America in June 1916. The magazine announced the forthcoming concerts of American women’s songs by contralto Alice Louise Mertens and composer-pianist Lola Carrier Worrell. Mertens’ career was centered in New York and New England, where she gave solo recitals, was a member of the Cosmopolitan Quartet, and held positions at synagogues and churches. The previous month the singer had appeared before members of the General Federation of Women’s Clubs performing songs by female composers: Mary Helen Brown, Fay Foster, Florence Turner-Maley, and Marion Bauer. A positive response to this event may have inspired her to tour giving women’s songs. Musical America listed the four women among some 22 composers whose works Mertens and Worrell intended to program. Worrell, originally from Denver, produced songs as well. Although she stated that she hoped to demonstrate “woman’s service to humanity as expressed through the medium of music,” it seems likely that her own works would have also found their way onto the pair’s recitals.

Louise Mertens prepared a chronological program constructed with an educational goal: to remedy the “pathetic and deplorable absence of women in the arts.” Women, she asserted, had previously been restricted by their gender, “shut in a dark cellar … of tradition and convention … with every original thought considered unwomanly.” Mertens nationalistically hailed the United States, with the most women composers, as leading the world out of darkness, though she complained that it did not fully recognize their achievements. Mertens and Worrell nonetheless looked forward to “the loyal support of every American woman.” They saw women as the future audiences for their recitals at women’s colleges and the numerous women’s clubs across the country.

In early 20th-century America many female musicians were deliberately promoting women’s songs. Christopher Reynolds

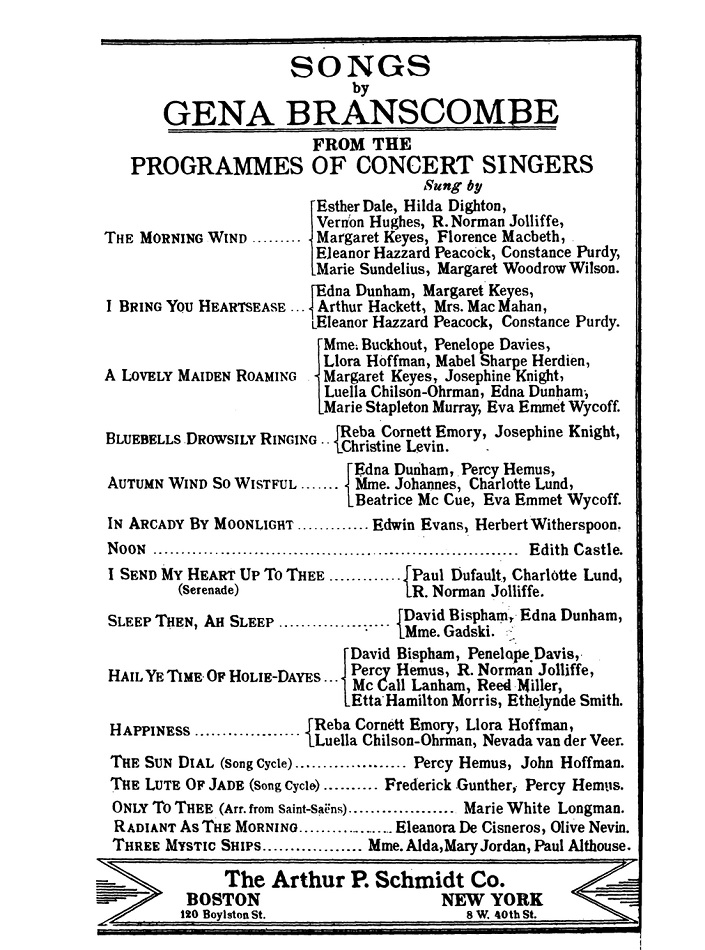

Professionals were not the only musicians performing women’s music. Women’s songs were ubiquitous on the programs given by the countless clubs of female amateurs. Music clubs often devoted a monthly meeting to studying women composers and sometimes organized concerts similar to the ones that Mertens and Worrell had proposed. New York’s Gamut Club announced its “Songs of American Women” event six months after the article about Mertens appeared in Musical America. Repertoire by women also became part of voice students’ studies. When Hanna Knutson gave her senior recital at Concordia College in Moorhead, Minnesota, the following year, her final selections were composed by Gena Branscombe, Mary Turner Salter, and the Irish composer, Alicia Adélaïde Needham.

The association of women singers with women’s songs was strengthened by music publishers. Arthur P. Schmidt issued over 500 women’s songs and placed advertisements in The Musical Courier subtly masquerading as articles. Entitled “Concert Record of Songs by Some of Our Best-Known American Composers,” the ads consisted of lists of songs indicating the performers in different towns who had programmed them. Not only were a substantial number of the works included written by women, but the singers reported to have sung them were often women as well. Mertens was listed alongside Marion Bauer’s “Youth Comes Dancing.” She also appeared in Huntzinger and Dillworth’s advertisement for Fay Foster’s “One Golden Day” indicating the fourteen female performers – but only four men – who had programmed it. Sheet music published by Schmidt also sometimes included names of vocalists, for example, in a works list for Branscombe, in which the female singers far outnumbered the men. Publishers thus promoted repertoire created by women and frequently intended to be sung by women.

Unfortunately, there is no evidence regarding the success of the recitals proposed by Mertens and Worrell, so it is not clear whether they ever toured together. Perhaps too many other singers were already presenting women’s music to audiences for them to find the duo’s offerings particularly unique. World War I slowed the production of songs by serious women composers, and many women’s groups became more occupied with war relief efforts than feminist concerts. Mertens moved on to other endeavors, though she did record Carrie Jacobs-Bond’s wildly popular “I Love You Truly” and Kate Vannah’s perennially programmed “Good Bye, Sweet Day!” (1891). Nonetheless, her efforts are an example of the widespread advocacy of female singers on behalf of women’s songs in the early 20thcentury.

Further Reading and Listening

Louise Mertens’s recording of “Beautiful Isle of Somewhere” (Emerson 1045, 1919, 78 rpm) is available.

“Our Women Composers Find Recognition in New Campaign,” Musical America 24 (10 June 1916): 13.

Adrienne Fried Block, “Arthur P. Schmidt, Music Publisher and Champion of American Women Composers

Christopher Reynolds, “Documenting the Zenith of Women Song Composers: A Database of Songs Published in the United States and the British Commonwealth, ca. 1890–1930,” Notes 69 (2013): 671–87.

Christopher Reynolds, “Growing the Database