This post continues a colloquy with five contributors to the recently published essay collection Clara Schumann Studies (CSS)

Interpreting Schumann’s Songs

JD: What kinds of interpretations do Schumann’s songs invite? And in what ways do they evoke meanings that lie beyond what is graspable or audible at the musical surface?

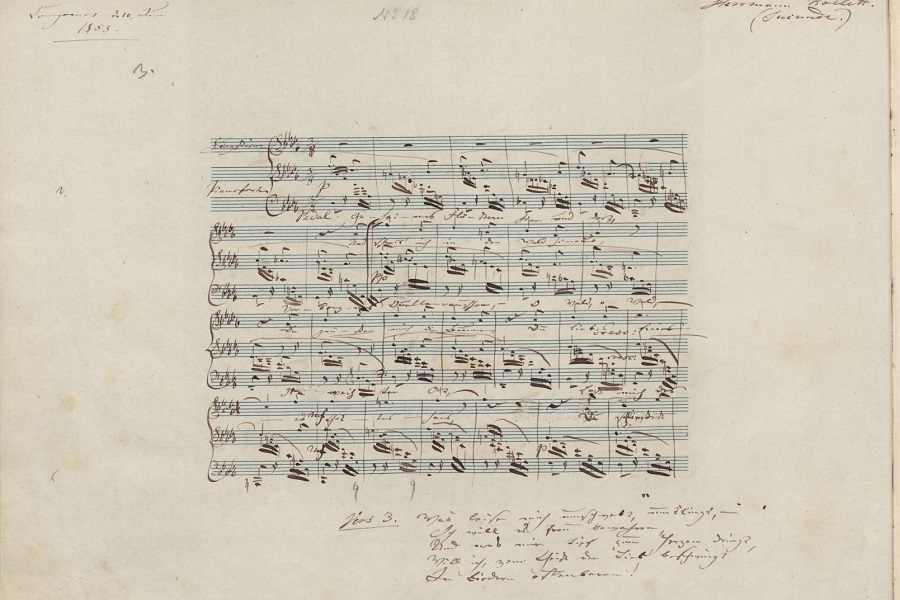

SY: Both Schumanns, aware of the danger of overt political expression that might displease the monarchy and yet clearly ardent in their beliefs, wrote them into their songs of the late 1840s/early 1850s in subtle ways: artists figure out how to evade the censors. In “Geheimes Flüstern hier und dort,” both Schumanns’ fealty to liberal German nationalism is telegraphed (for those in the know) by the sudden shift to F major, from tonic D-flat major, at the words “O Wald, o Wald, geweihter Ort” (O forest, consecrated space). The German forest was a nationalistic symbol. The impression left by the foreign-key cadence is much stronger than the tonic cadences, for all that the dazzling new key vanishes swiftly each time in each strophe.

Here is an exquisite performance of “Geheimes Flüstern hier und dort” by Wolfgang Holzmair and Imogen Cooper:

Lieder contain worlds, I’ve discovered, of folklore, symbolism, religion, history, politics, and more; they are both artful constructions of pure music and the bearers of meanings brought in from the outside world. They reflect and enact their moment in time, and they enable us to sound out the links between human exigencies in days gone by and our own times.

SW: Of course there’s the feminist scholarship – for example comparing her “Lorelei” with Liszt’s setting, which Caitlin Miller did – finding that Liszt’s conveys the “male gaze” and that hers conveys the Lorelei’s power: to put it simply – subject rather than object. It makes us realize how significantly different two settings of the same text can be.

The Lessons of the Songs

JD: What do we learn – as performers, analysts, pedagogues – from Schumann’s songs?

SR: We learn so much, not least that the history of 19th-century Lieder is about far more than the canonical works that have long dominated scholarly journals, recital programs, and course syllabi. It’s so heartening to see that Clara Schumann’s songs are finally receiving attention from scholars; your edited collection, Joe, is a real landmark in this sense.

SY: It was crucial for my students to hear marvelous works by women since misogyny is still alive and well in the world. To hear Fanny Hensel’s Trio and be bowled over by it, to hear Clara Schumann’s “Er ist gekommen in Sturm und Regen” and be astonished by the vivid virtuosity of it [the text and music of this song are linked in Part I.]. This paved the way for my students to be interested in present-day songs by women and

Programming Schumann’s Songs

JD: How might we bring Schumann’s songs into a more central position in contemporary performance culture?

SR: To bring Schumann’s songs into an even more central position we need to hear them even more – and this is to say nothing of the many, many women composers whose songs are studied and heard even less often than Clara Schumann’s. I just wrote a WSF post

One point I make in my post is that women’s songs have appeared relatively rarely on the recital stages of prestigious performing arts organizations than I had realized. I cited Wigmore Hall in London as an example, but the trend exists elsewhere too. The pianist and scholar Chanda VanderHart, herself a fierce advocate for underrepresented song composers, shared data that she had gathered from the Musikverein in Vienna. The Musikverein has done 182 Lieder concerts since 2000, and Clara Schumann has been programmed on only two (2!) of them. Robert Schumann, by comparison, has appeared on 58, and Franz Schubert on 93. We need the commitment – and the collaboration – of both scholars and performers to change the paradigm.

HK: The Hugo Wolf Akademie in Stuttgart is one organization that is making headway in bringing songs composed by women to their publics: in their bi-annual international song competitions, they have required the competing duos to perform songs by women composers. The first time they did this, in 2014, they asked Sharon Krebs and me to compile a collection of PDFs that competitors could use, and of course we included some of Clara Schumann’s songs. “Die Lorelei” turned out to be one of the most popular choices! Requirements to perform repertoire by women in a competition can lead to life-changing experiences for young performers, for the audience of the given competition, and for these duos’ future audiences (since the duos will certainly continue to explore this repertoire after the competition!).

At the University of Victoria, Sharon and I have been presenting short recitals under the series title “Lieder at Lunch”; these are attended by UVic faculty and students as well as by community members. The songs of Clara Schumann have been a staple in these recitals. Sometimes we fitted one of her songs into a theme concert; for instance, “Er ist gekommen in Sturm und Regen” was an obvious choice for our “Stormy Weather” concert. On some occasions, we have juxtaposed her setting of a given text with that of another composer within a “Comparisons” concert (e.g. the Clara Schumann/Robert Franz settings of “Er ist gekommen” that Poundie Burstein discusses in one of his articles). During 2019, we presented a birthday celebration for Clara – a recital in which we “invited” many of her friends. That is, we performed songs not only by her, but also songs composed by, or somehow linked to, her friends – Robert Schumann, of course (more than a friend!), Johannes Brahms, Pauline Viardot, Livia Frege, George Henschel, Felix Mendelssohn, etc. In short, our audiences know Clara Schumann’s songs quite well.

SR: It’s wonderful to hear that the Hugo Wolf Akademie is highlighting works by women – and there are other signs that the tide is turning. I was delighted to see that soprano Golda Schultz and pianist Jonathan Ware just released a wonderful album called This Be Her Verse, which is devoted to songs by women composers. It’s a wonderful recording, and it includes four Clara Schumann songs (“Liebst du um Schönheit,” “Warum willst du and’re fragen,” “Am Strande,” and “Die Lorelei”), as well as songs by Emilie Mayer, Nadia Boulanger, and Kathleen Tagg.

The Invitation of Schumann’s Songs

JD: Thank you all for sharing your insights into Schumann’s songs and the interpretative and programming possibilities they offer. It’s inspiring to see these fresh ways of understanding her contribution to the Lied genre, and to see her approach emerging not in isolation, but as part of a rich nexus of the ideas (musical and aesthetic) that shaped her outlook. Bound up with this is the enticing invitation to reimagine what song composers could be and do, in line with recent calls for more diverse and inclusive histories of music. Schumann, in this regard, encourages us not only to listen afresh to her own songs, but to nineteenth-century Lieder more generally.

Notes

Caitlin Miller, “‘Und das hat mit ihrem Singen, Die Lore-Ley gethan’: Subjectivity and Objectification in Two Heine Settings,” in Women and the Nineteenth-Century Lied, ed. Aisling Kenny and Wollenberg (Farnham: Ashgate, 2015), 233–250.

Susan Youens, “Disillusionment and Patriotism: Clara and Robert Schumann in the Wake of the 1848–1849 Revolutions,” in Clara Schumann Studies,