Women’s blues of the 1920s are nearly always qualified as “classic,” to distinguish the “professionalized” music of singer-songwriters like Bessie Smith and Ma Rainey from the “authentic” blues of rural male performers. The blues queens often performed Tin Pan Alley songs in the context of Black vaudeville and in tented shows, fronting bands that included jazz musicians. These features motivated early blues criticism to use the metaphorical asterisk “classic” to signal the “hybrid” and, therefore, “inauthentic” nature of their work. More recent scholarship (McGinley 2014) highlights the inherent gender bias in the characterization, which, among other things, fails to recognize the staged aspects of the “downhome” (i.e. male rural) blues. However, Memphis Minnie’s career challenges the critical reception of the blues in ways that go beyond these problematic oppositions.

Numerous factors contribute to the difficulty of categorizing her music, leading to her relative neglect in blues scholarship. Like Lonnie Johnson, whom I have dubbed “inconvenient” (Simon 2022), Minnie poses a similar conundrum because of a corpus that spans decades (more than 200 sides recorded), guitar virtuosity that exhibits numerous stylistic influences, and, perhaps mostly importantly, a persona constructed with care. Adhering neither to the profile of the rural male self-accompanied singers nor to that of the blues queens, Minnie strikes a unique figure in the history of the blues. As Sonnet Retman writes, “The very terms of Memphis Minnie’s popularity—her virtuosity, her technological innovation, her choice of genre, and her stage persona—align with masculinized notions of blues musicianship that render her illegible in conventional blues histories” (87).

Lizzie “Kid” Douglas

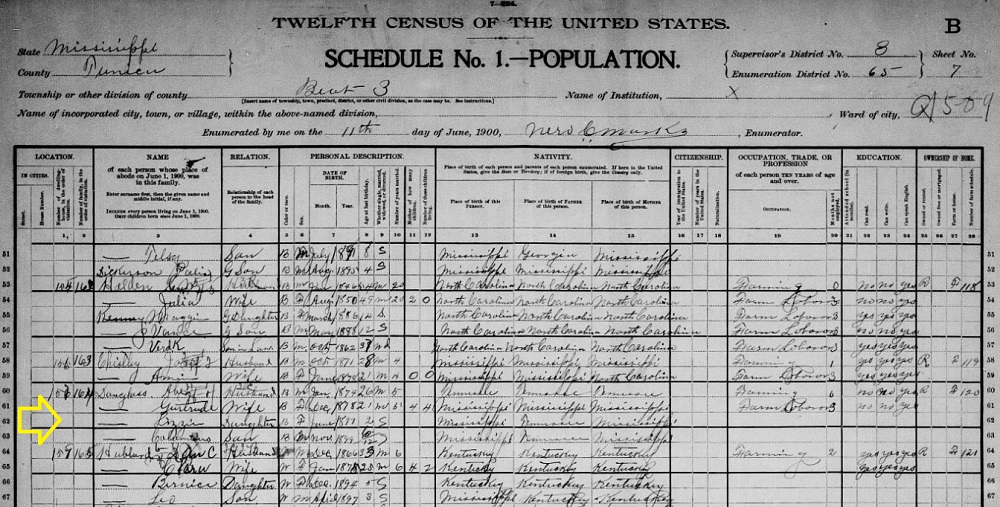

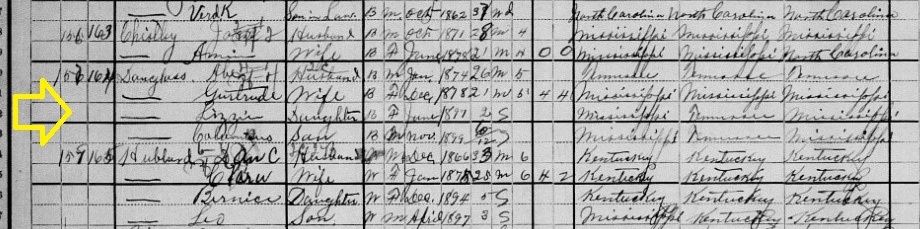

If we—as have many blues researches—are to believe her own autobiographical accounts conveyed in lyrics such as in “Nothing in Rambling” (1940), Lizzie Douglas was “born in Louisiana and raised in Algiers,” across the river from New Orleans. “Down in New Orleans” (1935) adds an assertion of a “Creole” identity: “We are the cooking’est Creoles in the world you ever seen [2x] / And if you don’t believe me, follow me back down to New Orleans.” However, US census records for 1900 for Tunica County, Mississippi list Abe and Gertrude as parents of a little girl, “Lizzie Douglass,” born 4 June 1897 (Garon, 2007; Broonzy, 2005). Consistent with her Mississippi birthplace, her lyrics in “I Am Sailin’” (1941) open with: “I’m

Discovered by a talent scout for Columbia playing on Beale Street, Douglas and her current romantic partner (husband?) were given the recording names Memphis Minnie and Kansas Joe McCoy (Garon and Garon, 24–25). The creation of her identity by a label using a half-true geographical moniker may have opened her eyes to the ease with which a persona could be consciously manipulated. In addition to her name, her professional identity was shaped by a decades-long recording career, along with live performances, that helped to solidify Minnie’s image in the popular and critical imaginations.

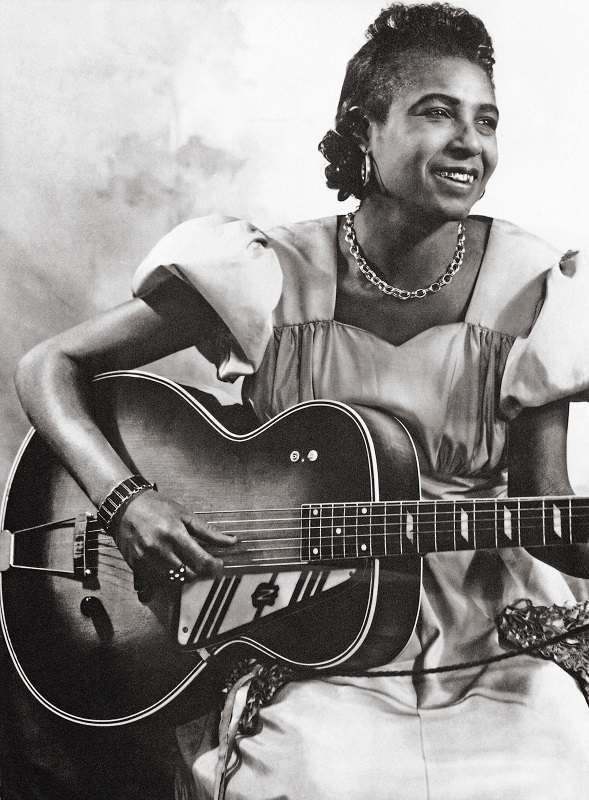

No less an authority than Langston Hughes wrote a description of one of her performances in 1942 for his column in the Chicago Defender. Hughes opens with an emphasis on her choice of instrument: “Minnie sits on top of the icebox at the 230 Club in Chicago and beats out blues on an electric guitar” (14). His account juxtaposes her physical appearance with her “scientific sound” (Retman, 75). Hughes portrays Minnie as an “old-maid school teacher,” “who dresses neatly and sits straight in her chair.” For dramatic effect, he likens her to “a colored lady teacher in a neat Southern school about to say, ‘Children the lesson on page 14 today, paragraph 2,’” to prepare for his startling revelation, “Instead she grabs the microphone and yells, ‘Hey, now!’.”

Images and Appearances

Hughes’ image of Minnie relies on juxtapositions grounded in both the portrait he paints of her as a schoolteacher and general expectations surrounding the female blues singer. Minnie’s appearance did not match the blues queens of the 1920s, who often appeared in elegant beaded gowns, hair ornaments, feather boas, and glamorous jewelry. Minnie asserts her continuation of this tradition in the song “Ma Rainey” (1940), “People it sure look lonesome since Ma Rainey been gone [2x] / But she left little Minnie to carry the good works on.” Yet the legacy must be interpreted as musical and professional rather than visual.

If Minnie’s physical appearance did not conform to their images, it did not match Hughes’s description either. Minnie often wore a bracelet made of silver dollars from her birth year (1897), a ring with the five-side of a die, large gold hoop earrings, necklaces, often short stylish dresses or long ones that revealed her legs, had gold teeth, and sometimes wore a wig. According to those who knew her, like Brewer Phillips, she drank, gambled, chewed tobacco (often spitting into a cup on stage), and dipped snuff (Cushing, 13). In these respects, her physical persona differed significantly from the earlier blueswomen. More importantly, her guitar playing set her apart from the singers of the earlier era.

Technique

Minnie was an accomplished guitarist, capable of playing in a variety of styles, including 12-bar, riff-based rural blues, Memphis jug band, popular/vaudeville, and Piedmont picking. Her guitar work—on acoustic, steel National, and electric—stands out for its inventiveness, versatility, and finesse in both rhythm and lead guitar roles. She moves seamlessly from single-note and half-chord lines, to chorded figures, to steady rhythmic pulses with subtle variation. A variety of techniques is on display in “Mister Tango Blues” (1930), which includes chromatic triplet moves, half-chord slides, gently swung single-note lead lines, and harmonics.

In “I Never Told a Lie” (1930), she effortlessly weaves in figures associated with Scrapper Blackwell and Lonnie Johnson. Her fine sense of swung rhythm and precision are evident in introductions and solos in songs. In the instrumental duet “Let’s Go to Town” (1931), she employs inventive, slightly swung “finger rolls” in an upward movement (Madsen discusses the technique), syncopated strummed chords, and a recurring swung single-note figure against Joe’s steady rhythm part. The nearly identical solos in the two takes of “Keep It to Yourself” (1934), with their playful alternation between a grace-noted, almost tied, descending lower-register figure and staccato treble picking, suggest planning and practice. Whether in rare solo work, or more often in duets and small combos with New Orleans-style jazz backing, Minnie consistently demonstrates skilled rhythm and lead playing in a range of styles.

Further attesting to her prowess on guitar, Fiddlin’ Joe Martin, who played with her on Beale Street in Memphis, “was fond of recalling that he had learned the guitar part for Good Morning Little School Girl (also known later as Me and My Chauffeur) from Minnie personally” (Garon and Garon, 40). Her ability to play the signature, bent half-chord part

(To be continued.)

Notes

William Broonzy, Big Bill Blues: William Broonzy’s Story as told to Yannick Bruynoghe(New York: Da Capo 1955; reprint 1992). Broonzy reports that Minnie told him she was born in Mississippi (1955, 140).

Steve Cushing, Blues Before Sunrise 2: Interviews from the Chicago Scene(Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2019).

Francis Davis, Francis The History of the Blues: The Roots, the Music, the People(New York: Da Capo, 2003).

Paul Garon, “Early Census Data Found for Memphis Minnie,” Living Blues38/4 (Aug. 2007): 5.

Paul and Beth Garon, Woman with Guitar: Memphis Minnie’s Blues(New York: Da Capo, 1992)

Langston Hughes, “Here to Yonder: Music at Year’s End,” Chicago Defender (Jan. 9, 1943)

Pete Madsen, “Memphis Minnie: The Open-G Stylings of an Undersung Fingerstyle Blues Artist,”Acoustic Guitar(June 2018): 42–46.

Paige A. McGinley, Staging the Blues: From Tent Shows to Tourism(Durham: Duke University Press, 2014).

Jas Obrecht, “Let It Roll: Memphis Minnie,” Living Blues50/4 (July/Aug. 2019): 262.

Sonnet Retman, “Memphis Minnie’s ‘Scientific Sound’: Afro-Sonic Modernity and the Jukebox Era of the Blues,” American Quarterly 72/1 (March 2020): 75–102.

Guest Blogger: Julia Simon

I have been playing blues for the last 21 years, first as a drummer and now as a bassist. As a result of my passion, I changed my research focus from 18th-century French literature and culture to the cultural history of the blues. My blues books are Time in the Blues (Oxford University Press, 2017); The Inconvenient Lonnie Johnson: Blues, Race, Identity (Penn State University Press, 2022); and Debt and Redemption: A Call for Justice in the Blues, which is forthcoming with Penn State University in spring 2023. Additional details are available on my departmental webpage.