Every year from about 2015 until 2020, my musicology colleague Marian Smith invited me to do a presentation on Fanny Hensel’s songs for her undergraduate music history class. (I did my last such presentation during Marian’s final year of teaching; she recently retired from the University of Oregon.) I had two main goals for each presentation: to explain who Hensel was and to pinpoint the hallmarks of her songwriting style. I always began by asking who had ever heard Hensel’s music. In 2015, about ten out of fifty students raised their hands. By 2020, that number had increased to about thirty. When I started giving these lectures I needed to explain why Hensel was such an important composer, but by the time I stopped giving them the students seemed to accept her importance without question. They already knew that she mattered. Many already knew what her music sounded like. They just wanted to hear more of it.

I have sensed the same shift when sharing Clara Schumann’s music with my students, and I suspect that other teachers (of music history, music theory, and performance) have sensed it too: a growing familiarity with the music of Hensel and Schumann, a belief in its value, an acknowledgement that in their own way these two composers are becoming part of the canon.

This is cause for rejoicing. We should be grateful that these composers are finally being celebrated. (An upcoming WSF colloquy on Clara Schumann’s songs, organized by Joe Davies, editor of the 2022 volume Clara Schumann Studies, is a case in point.) But at the same time, we should be mindful of the work that remains to be done to ensure that other women composers get the same attention.

Recent Decades, Steps Forward (or Not)

In 1986, Marcia Citron wrote a

Consider, as one case study of work that remains to be done, the example of Lieder recitals. I recently surveyed the recital programs from some of the most prestigious performing arts organizations and found almost no examples of women composers outside the most famous ones – and even then, very few examples from these well-known composers. Since 2010, Wigmore Hall in London has presented 124 concerts featuring Lieder, of which only fifteen contained Lieder by women. The number of women composers is very small: Clara Schumann (who appears on eleven of the fifteen recitals); Fanny Hensel and Alma Mahler (who each appear on two recitals); and Pauline Viardot, Nadia Boulanger, Josephine Lang, and Ingeborg von Bronsart (who each appear on only one). Often, where these women composers do appear, their names are not in the program’s title or subtitle; instead, we read things like “Schumann, Schubert, Beethoven, and more” (“more” referring to two songs by Fanny Hensel and “Schumann” of course referring to Robert Schumann).

Plumbing the unexplored depths of the genre requires the collaboration of scholars and performers, the production of quality writing on these songs as well as quality performances of them. I recently launched a website called Art Song Augmented, in hopes of prompting this sort of collaboration. The site is devoted to art songs by underrepresented composers and features commentary on the composers, video recordings of their songs, and information about where to access scores and other information.

Marie von Kehler

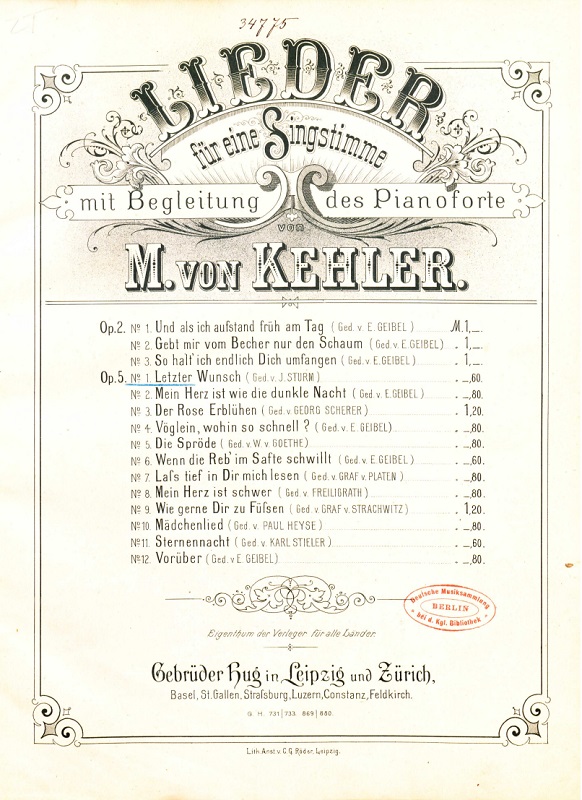

The latest addition to the site is a page about the German composer Marie von Kehler (1822–82).

Except, of course, that she wrote glorious songs. Playing through them, one senses an artist of great ingenuity and sophistication, a composer who knew how to write natural, flexible melodies that captured the subtle shadings of textual sound and sense, and who had a knack for expressive chromaticism. These features are no more evident than in her song “Letzter Wunsch” (Last Wish), the first of her op. 5 song collection.

The poem, by the German poet Julius Sturm, begins with these words: “Just once would I like to tell you how infinitely dear you are to me, how my soul will never forget you, so long as my heart still beats.” Kehler’s music, with its chorale texture, slow tempo, and two-bar gestures that feel like easy inhalations and exhalations, exudes warmth, ease, and comfort. But it is colored with signs of disturbance. The song is in E-flat major but there’s no solid tonic chord in root position until over halfway through the song; we hear far more B-flat major chords (dominants, not tonics) than E-flat major chords, the result being that the music seems to hover in a state of suspended animation, as though seeking some far-off security. Kehler also gently twists the knife with dissonant chords on crucial words like “sagen” (to say or to tell, the very thing the speaker longs to do) and “schlagen” (beats, referring to the speaker’s heart). Once the tonic E-flat does finally appear, it begins to erode as the music veers toward minor modes. The moment of greatest dissonance – a series of three diminished seventh chords – appears on the last word of the poem, “geraubt” (stole). With this word, the poet reveals that the speaker wishes to express not just gratitude but also regret: “I lay my hands upon your beautiful head, praying that God will send you the peace that my soul stole from you.”

With her song that intones a soulful, painful prayer, Kehler makes that regret palpable. This is a composer in full command of her craft. Her songs, like those of so many other women who made vital contributions to the Lied but who are largely forgotten today, deserve to be studied, but most of all, they deserve to be heard.

Notes

Anja Bunzel, The Songs of Johanna Kinkel: Genesis, Reception, Context (Woodbridge, UK: Boydell, 2020)

Marcia J. Citron, “Women and the Lied, 1775–1850,” in Women Making Music: The Western Art Tradition, 1150–1950, ed. Jane Bowers and Judith Tick (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1986), 224–48

Joe Davies, ed., Clara Schumann Studies (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2022)

Harald and Sharon Krebs, Josephine Lang: Her Life and Songs