In the annals of songs that have been banned in one forum or another in the United States, no one would expect to find one of Carrie Jacobs-Bond’s songs. Some songs have been denied radio play or television viewing on the grounds of obscenity, real or imagined – The Kingsmen’s “Louie Louie” (1963), John Travolta’s “Greased Lightning” (1978), or in the case of N.W.A.’s “Straight Outta Compton” (1988), an entire album – others because they were too sexual – Madonna’s

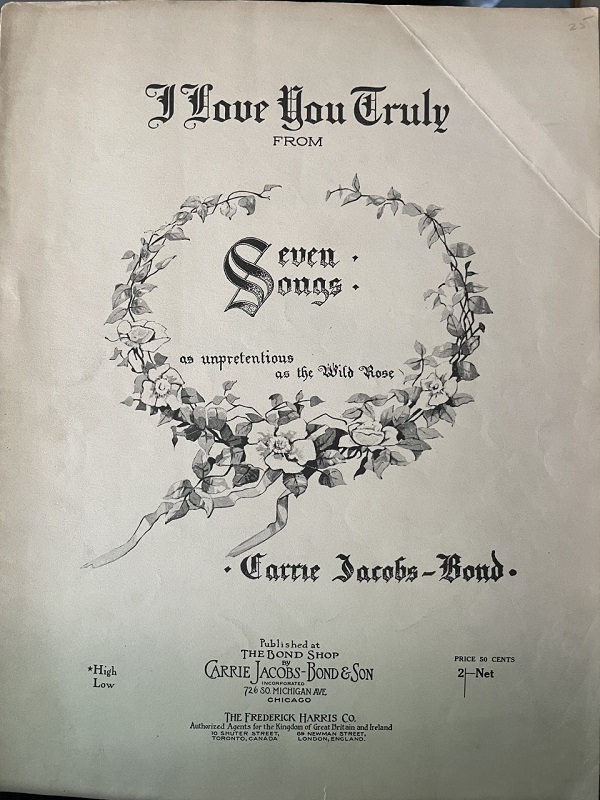

Yet, Carrie Jacobs-Bond’s hit song, “I Love You Truly” (1901), arguably the most popular wedding song of the 20th century, was banned for a longer period than any of them, not by radio stations but by churches throughout North America. The grounds usually given for blacklisting it were that it was insufficiently “sacred.” Yet another unstated reason could well have been aural fatigue: couples getting married programmed Bond’s song All The Time. It was too popular. By 1939, June was dubbed “I Love You Truly” month (Chattanooga News, 1 June). After the Second World War, one critic quipped that “half the women in America appear to believe that ‘I Love You Truly’ is a legal part of a church wedding service” (Carpenter). This degree of popularity, this bond between ceremony and song, took decades to achieve.

The Beginnings

The origins of the song have nothing to do with weddings. Between the accidental death in December, 1895, of her husband Frank Bond in Iron River, Michigan, and her move to Chicago in August, 1896, Carrie Jacobs-Bond returned briefly to her hometown of Janesville, Wisconsin. But in fact, because she used some of the life insurance money that she received after Frank’s death to spend May, June and July in London, she was barely in Janesville for five months; and at the outset of this period, five weeks after Frank’s death, she also lost her beloved Chicago mentor, Martha Holden (pen name, Amber) to cancer in mid-January. They were close enough that Carrie was summoned to Amber’s hospital bedside as she died.

This all matters because decades of local accounts in Janesville assert that Carrie wrote “I Love You Truly” in Janesville shortly after Frank’s death. For a time there was a commemorative plaque making this claim placed in front of a house on the corner of East Milwaukee and Wisconsin Streets. That is almost certainly only partially true. As with her other songs for which she wrote both music and words, the words came first. When sung at the quicker tempo that Bond herself favored, the hymn-like music of the song conveys a confidence, dignity, and emotional maturity that has no precedent or peer in the songs she was writing before 1897. Since the first performances of the song were not until fall 1899, it is fair to conclude that Bond had composed the music a few months earlier, in spring or summer 1899, along with that of its musical “twin” (her word), “Just a-Wearyin’ for You.”

The poem, just eight lines, can be read as her speaking to Frank: she declares her love, she acknowledges her sorrow, she feels his continuing presence, his enduring love (months after her son committed suicide in December 1928, she wrote a very similar poem to him, “A Vision,” which she never published). The message of many of her songs, and the example of her life as told in hundreds of interviews and thousands of performances, was that life was hard – she knew – but full of reasons to be grateful:

I love you truly, truly dear, / Life with its sorrow, life with its tear

Fades into dreams when I feel you are near / For I love you truly, truly dear.

Ah! Love, ’tis something to feel your kind hand / Ah! Yes, ’tis something by your side to stand;

Gone is the sorrow, gone doubt and fear, / For you love me truly, truly dear.

How different is this message from that of the other two great wedding songs of the century. Guy d’Hardelot’s “Because” (words by Edward Teschemacher) from 1902, promised triumphantly that “Because God made thee mine, I’ll cherish thee;” while Reginald de Koven’s “Oh, Promise Me” (words by Clement Scott) from 1889, spoke lofty Victorian sentiments: “Hearing God’s message while the organ rolls / Its mighty music to our very souls, / No love less perfect than a life with thee; / Oh, promise me! Oh, promise me!”

Becoming a Wedding Anthem

Within years of its publication in 1901, the transformation of “I Love You Truly” from a song that commemorated the end of a marriage to one that celebrated marital beginnings had begun. The earliest report of “I Love You Truly” being sung at a wedding occurred in Minneapolis on 14 Oct. 1903. Tracking only weddings that took place in June (and only in newspapers accessible through Newspapers.com), the rise in popularity is clear: in 1906 it was sung at 14 ceremonies (all in mid-western states), in 1910 – 84 nationwide. Elsie Baker’s 1912 chart-topping recording doubtless boosted the song’s popularity. In 1915 there were 295 June wedding performances, in 1920 – 384, in 1925 – 742. When Hollywood studios added sound to their films, Bond’s anthem naturally accompanied scenes that had anything to do with weddings. It was sung,

If wedding customs influenced Hollywood, that influence went both ways. The June wedding tally rose exponentially: in 1930 – 1327 June performances, in 1935 – 2108. The peak year was 1937, when 2805 brides, grooms, congregations and clergy heard Bond’s song. After a dip in marriages during the Second World War, “I Love You Truly” bounced back with more than 2500 performances in June 1946 and again in 1947. Anyone who officiated at weddings heard the song over and over and over again.

No wonder, then, that churches began to push back.

(To be continued).

Notes

A note on the counting of June wedding performances: All numbers are approximate. What matters is less the number for any given year than the progressive change of numbers, the rise that continues into the 1930s, and then the descent, which begins in the late 1950s. I start with a search on “Love You Truly” plus the word “wedding” (also “Love You

For my previous WSF posts about songs by Carrie Jacobs-Bond, see this one, and this one, and this one.

The banner photo was taken by James Ellsworth Gross in Chicago in 1906.

Paul S. Carpenter, Music: An Art and a Business