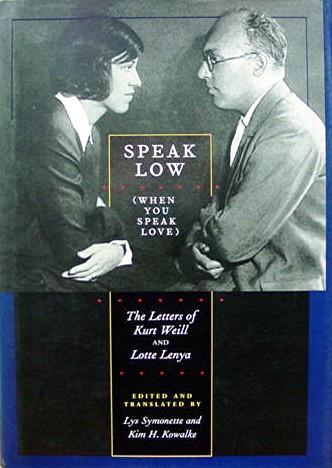

“Weill gave music to her voice, Lenya gave voice to his music.” This description of the reciprocal musical gifts with which Lotte Lenya (1898-1981) and Kurt Weill (1900-50) endowed each other nicely captures the artistic significance of their partnership. The wonderfully apt parallelism is cited here from the jacket of their edited correspondence – the “Weill-Lenya correspondence,” as it is known. Theirs is the story of Beziehungskünstler (relationship artists), to cite the title of Barbara von Bechtolsheim’s recent book in which they appear in a gallery of other celebrated artistic couples including, among others, Baez and Dylan, Plath and Hughes, Monroe and Miller.

None of those other partnerships, however, achieved the kind of creatively symbiotic legacy that is enshrined in the hyphenation “Weill-Lenya.” Much of their Nachlass, including the correspondence, is held in two places on the East Coast of the US: in the Music Library of Yale University and at the Weill-Lenya Research Center in New York, the state where they lived and worked for the remainder of their lives after fleeing Nazi Germany via Paris and London. In 1962, as the surviving spouse, Lenya chartered the foundation that bears her husband’s name, the Kurt Weill Foundation

The correspondence paints a vivid picture of the quarter of a century they spent together: he as a workaholic composer for the musical theater, she as a “triple threat” dancer, singer and actress – and his muse. All-too-human life is there in their unfiltered and bilingual exchanges, which offer an arresting mix of intimacy, insecurity, childlike frankness, gallows humor, mawkish sentimentality, petty jealousies, malice, schadenfreude, and much, much more, as they navigate the vicissitudes of their relationship and individual careers. Their turbulent, eventful lives, as narrated by the letters, would eventually be turned into a Broadway show, LoveMusik. Written by Alfred Uhry and directed by Hal Prince in 2007, the revue showcased twenty-seven of Weill’s songs as the eponymous main ingredient.

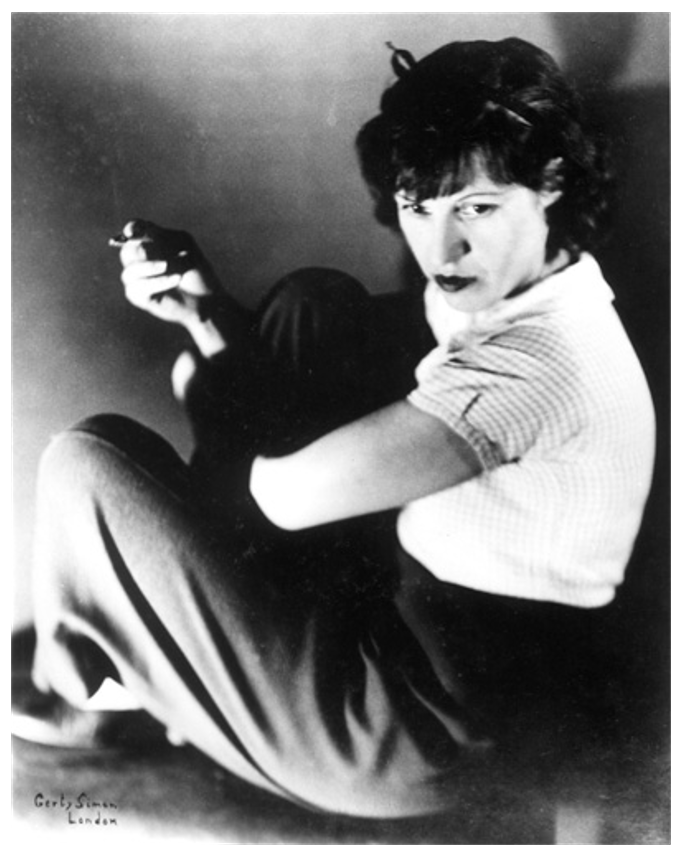

Lenya’s Voice

What kind of voice did Lenya give to Weill’s music? How to describe it? A letter from 1926, the year of their marriage, offers a clue. The composer effused there about how he missed his wife of two years during a temporary absence:

I think most of all of the sound of your voice, which I love like a force of nature, like an element. For me all of you is contained within this sound; everything else is only part of you; and when I envelop myself in your voice, when you are completely with me. I know every nuance, every vibration of your voice.

Not only did their partnership bequeath to posterity the many songs that Weill composed for the musical theater with Lenya in mind. Coinciding as it did with the incipient age of mechanical reproduction, the partnership also left a substantial recorded legacy spanning more than four decades. Thanks to the many iconic recordings Lenya made during that time we can hear for ourselves what Weill meant by “force of nature.” Because of all its myriad nuances, the inimitable voice is as immediately recognizable as it is hard to characterize, though many have tried. Over time, it also changed considerably in tessitura and tone, as the following examples illustrate. How very different the early recordings are from the later ones!

“Sweet, high, light, dangerous, cool, with the radiance of the crescent moon.” That is how philosopher Ernst Bloch described Lenya’s voice in his 1935 essay on Die Dreigroschenoper (The Threepenny Opera). Having created the role of Jenny in the premiere production, which opened in August 1928, she appeared in some widely distributed cast recordings as well as in G.W. Pabst’s film adaptation, 3-Groschen-Oper, in 1931. The description may come as something of a surprise to those familiar only with the later recordings from the 1950s and 60s, often considered the gold standard of Weill interpretation. Here, as an example, is the “Alabama Song” in the version included in the Mahagonny opera in 1930. (The song was originally written in 1927 for the Mahagonny-Songspiel, the first work of Weill’s that Lenya performed in.) That Bloch identified the “force of nature” as lunar seems especially apt here, given the refrain’s apostrophe: “Oh Moon of Alabama!”

The second example of the radiant, high-tessitura Lenya is her performance of “Seeräuberjenny” (Pirate Jenny) in the Pabst movie, in which she again plays Jenny. In the original “play with music” the song is assigned to Polly, who steps out of character during her wedding to gangster boss

Part Two of this post will compare different recordings of a single song and offer further reflections on Lenya’s voice.

Notes

Kurt Weill and Lotte Lenya, Speak Low (When You Speak Love): The Letters of Kurt Weill and Lotte Lenya, trans. and ed. Lys Symonette and Kim H. Kowalke (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996)

Barbara von Bechtolsheim, Beziehungskünstler: Wie

Kurt Weill, Die Dreigroschenoper, ed.Stephen Hinton and Ed Harsh, Kurt Weill Edition I/5 (Miami: European American Music, 2000)

Ernst Bloch, “TheThreepenny Opera” (1935), in The Threepenny Opera, Cambridge Opera Handbook, ed. Stephen Hinton (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1990), 133-37

Guest Blogger: Stephen Hinton

Stephen Hinton is the Avalon Foundation Professor in the Humanities at Stanford University. He has published widely on many aspects of modern German music history. His book Weill’s Musical Theater: Stages of Reform (2012), the first musicological study of Weill’s complete stage works, received the 2013 Kurt Weill Book Prize for outstanding scholarship in music theater since 1900. Together with the St. Lawrence String Quartet, he created Defining the String Quartet, the series of edX online courses on the music of Haydn and Beethoven.