In Bewitching Russian Opera: The Empress from State to Stage (2012), Inna Naroditskaya identifies a paradox of Russian music. Whereas the eighteenth century witnessed four Russian empresses – Catherine I (1725-27), Anna (1730-40), Elizabeth (1741-61), and Catherine II (the ‘Great’, 1762-96) – and many noble women played a prominent role in culture and arts, the nineteenth century rejected this legacy, emphasising instead male ‘genius’ and the establishment of a nationalist tradition. Women were allegorised on the stage and were certainly visible as performers, but female creativity was marginalised or dismissed altogether.

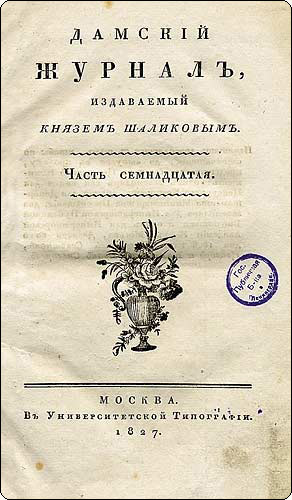

A similar situation goes for song too. During the eighteenth century, many women wrote works for performance in the aristocratic salons of the Russian capitals (there is a recording of some of these: ‘Music of Russian Princesses’), and they set the tone for polite conversation (usually in French) and European-style court culture. This tradition continued well into the nineteenth century. The Moscow salon of Princess Zinaida Volkonskaya (1789-1862) was a meeting place for many of Russia’s leading Romantic writers, and Volkonskaya herself was an accomplished poet, singer and composer (her papers are housed at the Houghton Library at Harvard). As in so many other countries, aspiring mothers taught their daughters to play and sing, and periodicals such as The Ladies’ Journal (Damskii zhurnal) contained not just fashion tips, society news, and genteel reading, but songs and piano miniatures for domestic consumption. Some of these compositions were almost certainly by women, but propriety dictated that such works be published anonymously.

We still know relatively little about this period, and in comparison to feminist literary scholarship – which has restored the work of writers such as Anna Bunina (1774-1829), Karolina Pavlova

It is telling that when Pyotr Tchaikovsky met Ethel Smyth in Leipzig in 1888, he singled her out as “one of the few women composers whom one can seriously consider to be achieving something valuable in the field of musical creation.” A look at Tchaikovsky’s own life gives some indication of why he could find no equivalents back at home. To be sure, women were active enough in the world of music. The Russian Musical Society had been founded in 1859 thanks to the enthusiastic support of Grand Duchess Elena Pavlovna (1807-73), and Tchaikovsky owed his freedom to compose to the anonymous patronage of Nadezhda von Meck (1831-94), the passionately musical widow of a railway magnate. And without the formidable commitment of the singers of the Imperial Theatres, we would not have the array of powerful roles for female singers that we do.

Models of Service and Selflessness

But a brief look at the lives of a number of women musicians illustrates the constraints placed on them by convention and society. Valentina Bergman (1846-1924) was one of the first students of the newly founded Petersburg Conservatory in 1862, yet she soon left to study with Aleksandr Serov, whom she married the next year (their son, Valentin, was to become one of Russia’ most famous painters). Although she wrote a number of operas of her own, she is best known for completing The Power of the Fiend, which Serov left unfinished on his sudden death in 1871. The equally talented Purgold sisters replicated this model of service and selflessness. Aleksandra

The emergence of a body of modernist poetry by women such as Anna Akhmatova, Mirra Lokhvitskaya, Sofiya Parnok, and Marina Tsvetaeva provided new inspiration for musicians. Much of this would find its way into the songs of male composers (Rachmaninoff set seven texts by minor female poets, for instance), but it

If Weisberg is little known today, what about the major female composers of the Soviet and post-Soviet eras, Varvara Gaigerova (1903-44), Galina Ustvolskaya

Scholarship on Russian women musicians is still in its early stages, and I hope that some of my claims here will soon by challenged, and our collective ignorance will be dispelled by a new generation of researchers. Ella Adayevskaya (1846-1926) has already been the study of a pioneering monograph by Renate Hüsken, and Graham Griffiths

Guest Blogger: Philip Ross Bullock

Philip Ross Bullock is Professor of Russian Literature and Music and Fellow and Tutor in Russian at Wadham College. His most recent book is a critical life of Tchaikovsky that explores the composer’s life within the context of nineteenth-century Russia’s evolving musical institutions. His survey of “Women and Music” is available in the open-access collection, Women in Nineteenth-Century Russia: Lives and Culture, co-edited by Wendy Rosslyn and Alessandra Tosi.