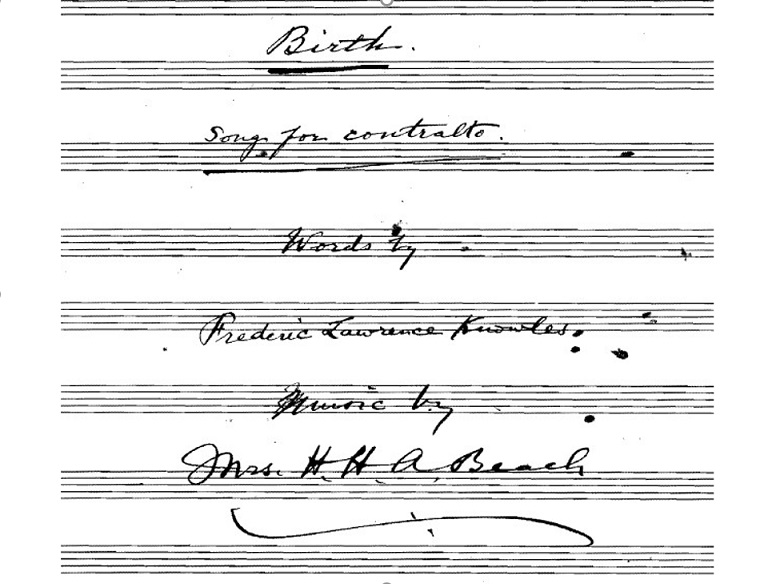

My summer project in 2010 to inventory and digitize uncatalogued manuscripts at the University of Washington Music Library resulted in the discovery of a previously unpublished two-page song, “Birth,” by Amy Beach (1867–1944). No American woman composer of symphonic and chamber music has occupied a more significant role in persuading her contemporaries – male and female – that women could compose.

Amy Marcy Cheney Beach, who preferred to be called Mrs. H. H. A. Beach, was the first American woman composer to write large-scale works that were presented by the premiere ensembles of the day. At age 25, her Mass in E-flat was performed by Boston’s Handel and Haydn Society to critical acclaim. Her Gaelic Symphony (1896) was premiered by the Boston Symphony under the baton of Emil Paur in 1897; other famous conductors such as Leopold Stokowski and Frederick Stock also performed her works. Beach composed over 170 works, about 120 of which are songs. This prolific composer was also a superb concert pianist, who had a successful piano debut at age 16 (1883) in Boston. However, Amy Beach’s career as a concert pianist was cut short by her husband’s request that she stop public performances after their marriage in 1885, except for charity purposes. Instead, she began to focus on composing. After her husband’s death in 1910, she resumed her performance career and toured extensively, both in Europe and the United States. She continued to compose until her final years.

The song and text

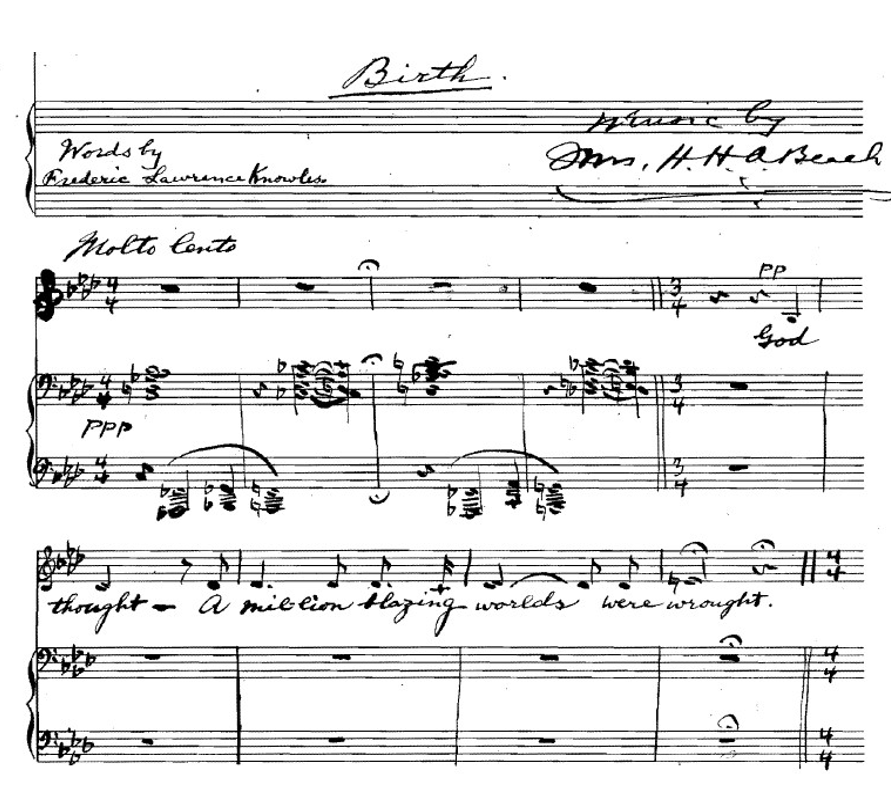

The manuscript of ‘Birth’ is undated and without an opus number, but biographer Adrienne Fried Block dates it 1929 (Block, 308). While there are no extant documentary breadcrumbs for this dating, I think the song could have been composed as early as 1926. The singer Emma Roberts gave the poem to Beach in September that year to comfort her after Beach’s surgery, as her close friend Amy Bingham recalled. Bingham further encouraged Beach to set it to music (Jenkins, 89). For either date, the song would be written in her last compositional period, which showed a different compositional style than her earlier Victorian romanticism. According to Block, “Beach, who rejected the more extreme compositional practices of Varèse, Stravinsky, or Schoenberg, was moved—despite her conservative pronouncements—to experiment with modern idioms . . . she wanted to be thought of as an up-to-date composer.” (Block, 224).

The catalyst for the change in her musical style was her acquaintance with composers a generation her junior at the MacDowell Colony, talented women such as the sisters Marion and Emilie Frances Bauer, Ethel Glenn Hier, and Mabel Daniels. Beach was in residency at the Colony for many summers, beginning in 1921, and her compositions from that year on reflect her new style. In addition, Beach was exposed to the modernist music of Debussy and others during her trips to Europe. Indeed, the accompaniment of this song, at times, hints at the famous parallel chords of Debussy.

The poem of the same name was written by fellow New Englander Frederic Lawrence Knowles (1869-1905), and it describes the miraculous and sacred nature of birth as an act of God.

Birth

God thought: –

A million blazing worlds were wrought!

God will’d: –

Earth rose, while all Creation thrill’d!

God spoke: –

An in The Garden love awoke!

God smiled: –

Lo, in the mother’s arms, a child!

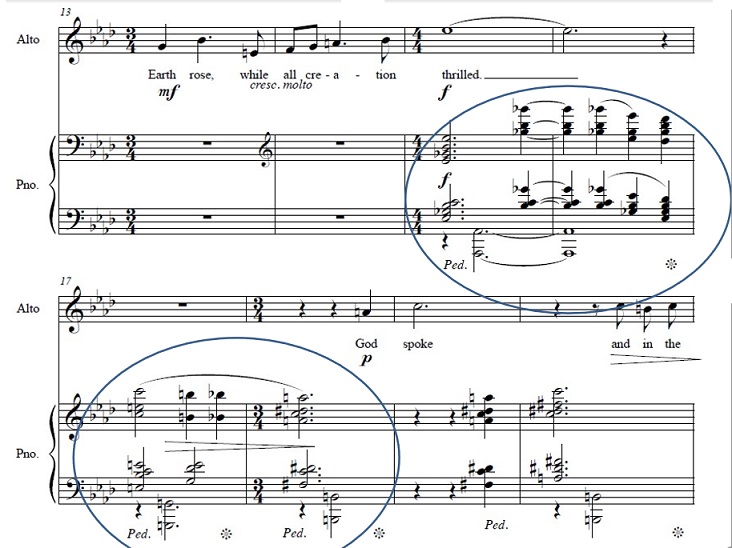

The music, too, suggests the act of birth: it begins with darkness, represented by the dark low register of the piano accompaniment, and progresses toward light, signified by the high register at the end of the song.

The dark to light imagery is further amplified by the progression from dissonance to harmony. The dissonant chords persist until the final phrase, when the child is born. The vocal line, too, includes augmented intervals of seconds and fourths until this point. At the words “and lo, in the mother’s arms a child,” the last phrase, the jagged intervals resolve to a perfect fourth followed by a stepwise descent to E-flat accompanied by traditional harmony. The song is in an overall A-flat major tonality in this section. Beach had always associated specific keys to color and mood. She associated A-flat major with the color blue, a soothing, post-partum calm.

Pianist Rhonda Kline suggested to me that we can view this birth as a metaphor for the Biblical creation story. The lines in the poem recall some in the Book of Genesis. Beach became more devout later in life, and the religious reference probably attracted her. Beach’s music, too, evokes the creation of the earth in Genesis, from darkness to light, as described in the preceding paragraph.

The performance here was recorded at the University of Washington on 16 May 2011. Contralto Nataly Wickham is a former voice student and pianist Rhonda Kugler Kline is Artist-in-Residence.

Hazel Kinscella and Amy Beach

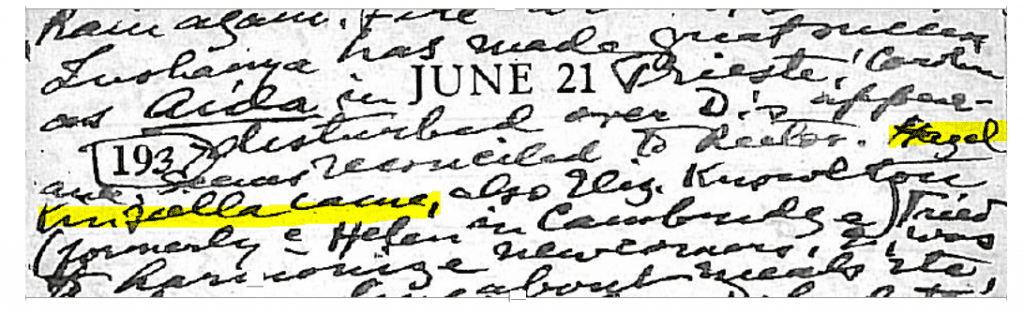

This manuscript is part of the Hazel Kinscella Collection at UW’s Music Library, where Kinscella was on the faculty from 1942 to 1958. Kinscella met Beach in 1918, when she accompanied her artist mother, Ella Gertrude Kinscella, to the MacDowell Colony, where she was a fellow that summer. Marian MacDowell, widow of composer Edward MacDowell, provided an introductory letter for Hazel Kinscella to approach Beach for an interview. The interview was published in Musical America (7 Sept. 1918). Although there is no extant correspondence between the two, there is evidence of their friendship throughout Beach’s life. In 1918, after her return from the MacDowell Colony, Hazel Kinscella sent Amy Beach a Native American melody, which Beach used in the piano piece “From Blackbird Hills” (1922). Beach dedicated the piece to Kinscella. A letter from Kinscella to biographer Walter Jenkins dated 7 August 1959 spoke of her continued friendship with Beach, including visits to New York in the 1930s. And in 1935, Beach contributed an essay to Kinscella’s book Music in the Air. We know that Kinscella visited Beach as late as 1937; the event was recorded in Beach’s own diary entry on 21 June.

We do not know when and how Kinscella acquired this and the other two Beach manuscripts; there are no documents accompanying them. Beach possibly gave her these manuscripts in one of their meetings.

“Birth” marks Beach’s early effort to become a “modern” composer. We can hear influences of Debussy and other modernist composers in the music, and yet she returns to triadic harmony for a resolution; her later compositions are more dissonant. Although this song is not a major composition, and ultimately she chose not to publish it, the manuscript documents an important moment in Beach’s stylistic evolution.

Notes

Adrienne Fried Block, Amy Beach: Passionate Victorian(NY: Oxford University Press, 1998).

Walter Jenkins, The Remarkable Mrs. Beach, ed. John H. Baron. (Warren, MI: Harmonie Park Press, 1994).

Hazel Kinscella, “‘Play no music when first heard,’ Says Mrs. Beach.” Musical America 28 (7 Sept 1918), 9-10. Cited in Block, 365, fn. 8.

Guest Blogger: Judy Tsou

Judy Tsou is