Mahalia Jackson (1911-72) is popularly acclaimed as the singular “Queen of Gospel,” but accounting for her associations with other women singers helps to capture the full extent of her legacy and the ways musical women have worked with and drawn inspiration from each other. Decade after decade, Jackson’s career unfolded through easy-to-overlook intersections with women who were models and mentors, peers and progeny.

Coming of age in her hometown of New Orleans in the 1920s, Jackson curated a circuit of vocal influences. She recalled being inspired by a woman in her childhood Baptist church named Sister Burke who “didn’t sing like the people sang in the choir” but rocked the congregation by forgetting “all the technical parts about singing.” That didn’t mean that Jackson herself was indifferent to other forms of training. At home, she closely studied recordings, especially those by her idol, blues singer Bessie Smith (1894–1937), but also by concert artists like contralto Marian Anderson (1897–1993), another hero, and white operatic soprano Grace Moore (1898–1947), paying conscious attention, she said, to tone, diction, and “the right way to breathe.”

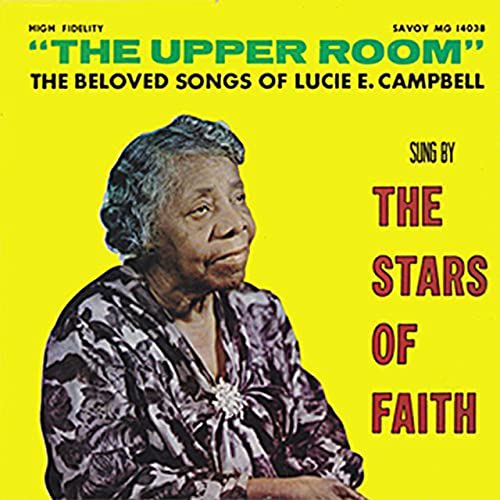

When Jackson moved North to Chicago in 1931, one of the gospel power brokers in town was Sallie Martin (1895–1988), a leader of her own singing group and co-owner of the Martin and Morris Music Studio on the South Side. Martin was instrumental in easing Jackson into the competitive Chicago gospel scene. “I would go with Mahalia to a lot of small churches, like storefronts,” Martin recalled, because “the big churches they wouldn’t accept her.” At the National Baptist Convention, the music lineup was overseen by Lucie Campbell (1885–1963), a prolific songwriter and a gatekeeper at this largest gathering of Black Christians. Despite initial ambivalence, Campbell eventually gave Jackson, who later scored one of her biggest hits with Campbell’s “In the Upper Room,” a slot at the annual meeting, helping to establish her reputation. “When I’d leave the convention, I’d be booked up for a whole year,” Jackson said. “So that’s how my name got around nationally among my people.”

In the 1940s, fans heard Jackson’s voice in counterpoint with contemporary gospel divas and close associates like Roberta Martin (1907–1969), Ernestine Washington (1914-83), and Sister Rosetta Tharpe (1915-73), each with their own style and perspective on the rigidity of the sacred-secular divide. Much to Jackson’s chagrin, Tharpe made her name recording jazz-inflected gospel songs for Decca in the late 1930s, but in her performance on the 1960s show TV Gospel Time, she reminded viewers of both her church roots and her historical place as a rock-and-roll pioneer. If anyone rivalled Jackson’s fame in the postwar period, it was Clara Ward (1924-73), who as an up-and-coming singer got her hair done at Jackson’s beauty salon and eventually took Black gospel and the flamboyance, flair, and electricity of her Clara Ward Singers to posh nightclubs and even Disneyland.

By the fifties, Jackson had hit the top, but she still took interest in junior singers in Chicago and beyond. She spoke with pride about following the development of members of the extraordinary Caravans “ever since they were kids,” especially Albertina Walker (1929–2010) and Gloria Griffin (1933-95), who went on to become stars in their own right, and she closely mentored Princess Stewart (1922-67), who when citing her musical pedigree said she “studied at the Chicago Conservatory of Music and under Mahalia Jackson.” Jackson was among the gospel elite who passed through the prominent Detroit church of Reverend C. L. Franklin, and she was closely emulated by the pastor’s daughter Aretha (1942–2018), who years later sang at Jackson’s funeral.

Meanwhile, back in Chicago, teenaged Mavis Staples (b. 1939) accompanied her father Pops Staples to lawn parties at Jackson’s home where she hung on every word. Staples, whose 1996 album Spirituals was a tribute to Jackson, is seen in the recent documentary Summer of Soul singing with Jackson at the 1969 Harlem Cultural Festival, less than three years before the older singer’s death, a highly meaningful moment that Staples still looks back on as a passing of the torch.

The legacy continues. Ledisi (b. 1972) and Danielle Brooks (b. 1989) have both played Jackson in body and in voice in the film Selma and biopic Mahalia, respectively. Following George Floyd’s murder, Irish singer Sinéad O’Connor(b. 1966) made a music video of one of Jackson’s signature numbers, “Trouble of the World,” that showed her carrying a sign with Jackson’s image, hoping, she told an interviewer, to offer Jackson’s voice as “the soundtrack for the Black Lives Matter movement.”

Reading Jackson’s gospel career less through her accomplishments, however formidable, than through the soft power wielded through connections and reception reveals an interlocked chain of women artists and organizers who forged opportunities and resonant experiences in collaboration with other women, making music while making history.