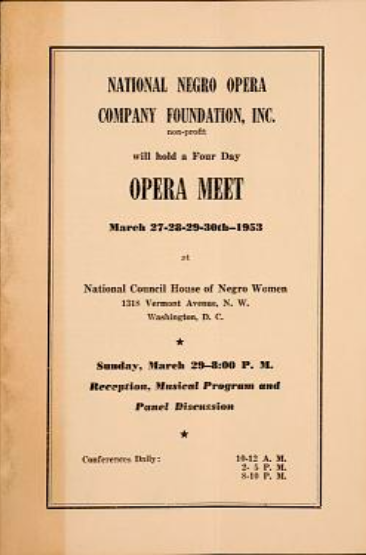

Mary Cardwell Dawson lived a remarkable life. Born in Madison, North Carolina, in 1894 in the Jim Crow south, Dawson became a gifted soprano, graduating from the New England Conservatory in 1925. And then, in 1941, she founded the National Negro Opera Company (NNOC) in Pittsburgh. Through Dawson’s tenacious and innovative leadership, the NNOC supported Black composers and performers, staged operas, and provided music education for young students.

The NNOC’s achievements remain unheralded. Fortunately, both Mary Cardwell Dawson and the NNOC have a new champion, famed mezzo-soprano Denyce Graves. On April 20th, I sat down with Ms. Graves to discuss why Mary Cardwell Dawson and the National Negro Opera Company mean so much to her. This is an excerpt of our conversation.

FMH: Mary Cardwell Dawson was a Black woman born in the 19th Century, a conservatory-trained singer who started her own opera company. What do you make of all she achieved?

Denyce Graves: When you look at Mary Cardwell Dawson, so much of her life was unconventional. She graduated from NEC in 1925 when she was 30 years old and there was controversy surrounding that, because she was not allowed to get the proper degree. She was awarded a teacher’s diploma rather than a traditional degree.

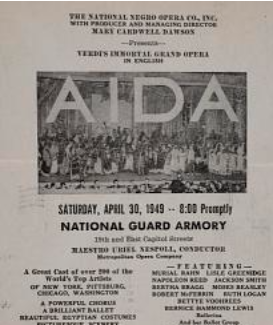

Despite that, Dawson set out to make a name for herself. and clearly, in 1925, there were all kinds of roadblocks for her then. The racism was blatant and very clear for African American singers. So, Dawson just said, “Well okay, then I’m going to do my own company.” To find the wherewithal, for a woman to have that sort of gumption to say, “Well okay, we’ll find a way to make this happen.” And not only for herself but for hundreds of others, too. We’re talking about all kinds of singers, all kinds of instrumentalists, composers, designers, the backstage people, the makeup people. She put all of that together.

FMH: I read that Dawson was the first to bring an all-Black company to the Metropolitan Opera stage. What do we know about the debut?

DG: Yes, Mary Cardwell Dawson was the first to do that when she brought the National Negro Opera Company to the Met. And this was before Marian Anderson sang there. It was the first time the Met had rented out the theater to an independent company. They wouldn’t even let them use the box office. So they [the NNOC] had to fashion their own box office for that and then they wouldn’t let them perform standard repertoire, so they did Clarence Cameron White‘s Ouanga. But that was the reason they performed it: the unions wouldn’t allow them to perform standard repertoire.

FMH: Currently, you’re preparing to premiere performance about Mary Cardwell Dawson at this year’s Glimmerglass Festival. And you’re also working to restore the former home of the National Negro Opera Company in Pittsburgh. Can you tell me more about both projects?

DG: In the piece that we’re going to flesh out this summer, The Passion of Mary Cardwell Dawson, you can see that Mary Cardwell Dawson was really quite the firecracker. She did not bow down at all. She was very fierce in what she demanded from others around her. That is how she got it done because she was absolutely unapologetic. This is incredible at that time for a woman who grew up in North Carolina. And then she spent a great deal [of time] in my hometown of Washington, D.C. She actually died there.

But the NNOC had a multi-story property in which they ran the company, offered music lessons to children in the community, and served as a gathering space. What she was able to do with that space was phenomenal. Her husband had an electric business there, the third floor was the music school, they’d have these jam sessions and such. People would stay there, and they’d do rehearsals. So, as we look at the restoration and the rebuilding of this property, it really has to be something that 100% benefits the community, a place and a resource for people to come to, an after-school program and a place to learn music. She also had these choirs, including a 500-voice choir. This woman was just all over the place doing everything. Eleanor Roosevelt donated $50 at that time. She was a guest at the White House. So, people in that time knew she was a force to be reckoned with. She framed the check from Eleanor Roosevelt. She was proud of that and all that they were able to do. And there were all kinds of issues to find venues. They had to rent out many spaces to actually stage the performances. She was just an incredible force.

Dawson didn’t ask permission. Earlier in the pandemic, there was a sports figure [Malcolm Jenkins] who said, “I don’t think you understand. We’re done with asking.” I just caught a minute of his interview, but that hit me and has not left me since that time; I think that’s what she’s teaching me too. As we are going about raising awareness and raising money for the restoration of the house, this is one of great American heroes who was the first woman of opera. There is no one who did what she did. And yet, she fell into obscurity. I think right now, people really want to recognize this history. I think I feel a lot of sincerity coming from non-Black people where they really want to address this and say even though this is woven into the fabric of what America is, we’re going to have to change it, because there’s no way that we’re all going to be able to coexist with this level of unbelievable institutionalized racism. But I just love that she felt like she could just go ahead and do what it is she wanted to do. This is what makes America great, women like Mary Cardwell Dawson.

People don’t know about her or about Black history because it isn’t taught. The success and brilliance in this country were not taught. It only takes a generation to lose the knowledge. It’s been intentionally excluded for generations, which is why she fell into obscurity. She was powerful, and power is scary to some people. It’s hurt the entire country not to know about people like Mary Cardwell Dawson and other contributors. I’m actually really encouraged that this moment of stillness that we all been in has gotten our attention.

Dawson saw that what she was creating was so important and valuable to the culture and to society, so everybody had to get on board with it. I love that about her. It was my upbringing to be correct and polite, but that’s not going to help you. In fact, it’s going to hurt you. You govern your voice. You govern your instrument. Nobody knows what it’s like to sing through your body.

FMH: How do you imagine your contributions in connection with all that Mary Cardwell Dawson achieved?

DG: When I think about Mary Cardwell Dawson, my heart just bursts with gratitude, and I feel a great responsibility to get this right and to right this wrong. I feel this more and more every day. I feel like this is my life’s work. I feel like this is the most important thing I can do. Without a doubt. I’m in awe of what this woman gave to the world.