Anna Bockrath is a weaver. Which makes her, perhaps, an unconventional choice as the subject of a blog post dedicated to “Women and Song”—and yet draft/ patch/ weave, an ongoing composition-installation in collaboration with her partner, interdisciplinary artist Jacob Weinberg, is a performance of materiality—a concert of cloth!—that its creators see as a continuation of the longstanding search for novel musical interfaces by electronic and experimental musicians. I’m sold.

It’s a tale as old as time, or at least as old as March 2020: suddenly sharing a small space day after day, two artists—one focused on textiles, the other on sound—began to notice similarities in the pattern-based operations of their tools: the floor loom, and the modular synthesizer. In weaving, a pattern is called a “draft”—a graphic, grid-bound representation of threads and treadles, warp and weft. For each “movement” of draft/ patch/ weave, Bockrath and Weinberg begin by using a custom patch in Max/MSP to create their weaving draft (sometimes a twist on a traditional pattern, sometimes an entirely new pattern created within the program itself). Then, according to the project description: “The mechanical motions of the loom are processed through Max and used to control the synthesizer in conjunction with the weaving pattern.” The act of weaving (the push of the beater bar, the rattling of the heddles) provides sonic feedback that further develops their joint composition. Here’s what a modified version of the traditional coverlet patterns Lovers’ Knot and Whig Rose looks and sounds like:

“Knot” from draft/ patch/ weave by Anna Bockrath and Jacob Weinberg; woven in linen and recycled fabric.

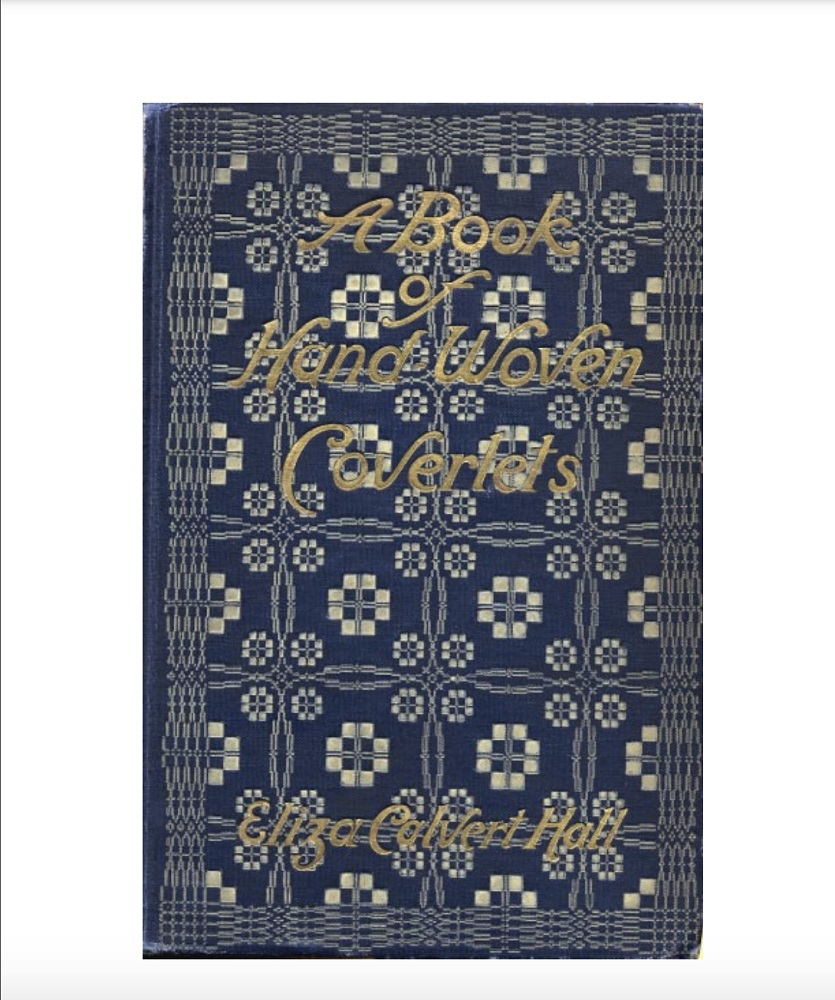

For Bockrath, draft/ patch/ weave is about process: a means of finding common ground between two distinct practices with two distinct products. “In researching weaving patterns,” Bockrath noted in an email to me, “I encountered lots of metaphorical language comparing weaving on a loom to playing an instrument, and comparing a weaving draft to sheet music.” In an Instagram post, she highlighted Eliza Calvert Hall’s A Book of Hand-Woven Coverlets (1912) as a particularly notable example of this exchange of metaphors—and wow did I fall down that rabbit hole.

Eliza Calvert Hall was the pen name of Eliza Obenchain—“Lida” to her friends—an American author and notable Kentucky suffragist who used writing to advance her chosen cause. Most famous for her short stories (her 1907 collection Aunt Jane of Kentucky caught the eye of President Theodore Roosevelt), she wrote A Book of Hand-Woven Coverlets after she received photographs of a friend’s coverlet collection but couldn’t find published information about the weavers, the patterns, or the culture of making. In Lida’s own voice:

“Often I find myself thinking and writing as if weaving and music were sister arts. A draft is like a long bar of music and the figures or marks on it are the notes. When I see a weaver at his loom I think of an organist seated before a great organ, and the treadles of the looms are like the pedals and stops of a musical instrument. …[W]henever I begin to study a new coverlet pattern, Milton’s lines come to me: ‘Untwisting all the chains that tie / The hidden soul of harmony.’”

Obenchain was one member of a network of mostly middle-class, white women who collected early twentieth-century Appalachian coverlets and coverlet patterns; her book’s acknowledgements section is a who’s-who of collectors-turned-weaving students who used their social and economic capital to found schools, publish drafts, and open weaving businesses designed to pass on skills to the next generation—in short, to establish what textile scholar Phillis Alvic has called “a form of early economic development for Appalachia.” It’s a leap I’m willing to make: though rooted in the 1910s and ‘20s rather than the 1930s and ‘40s, the parallels between the women who collected, researched, and catalogued coverlets and the women who would later collect, research, and catalogue songs are too good to ignore. (Obenchain might have agreed: “I think that if the God of Beauty became incarnate and walked the earth searching for his most faithful worshipper…his search would end on some southern mountain among gaunt, haggard women toiling for two seasons to make the thread for shuttle and loom…and finally christening their work at the springs of fancy with a name that sounds oftentimes like a song or a poem.”) Weaving is like music, and the resulting cloth is like a song.

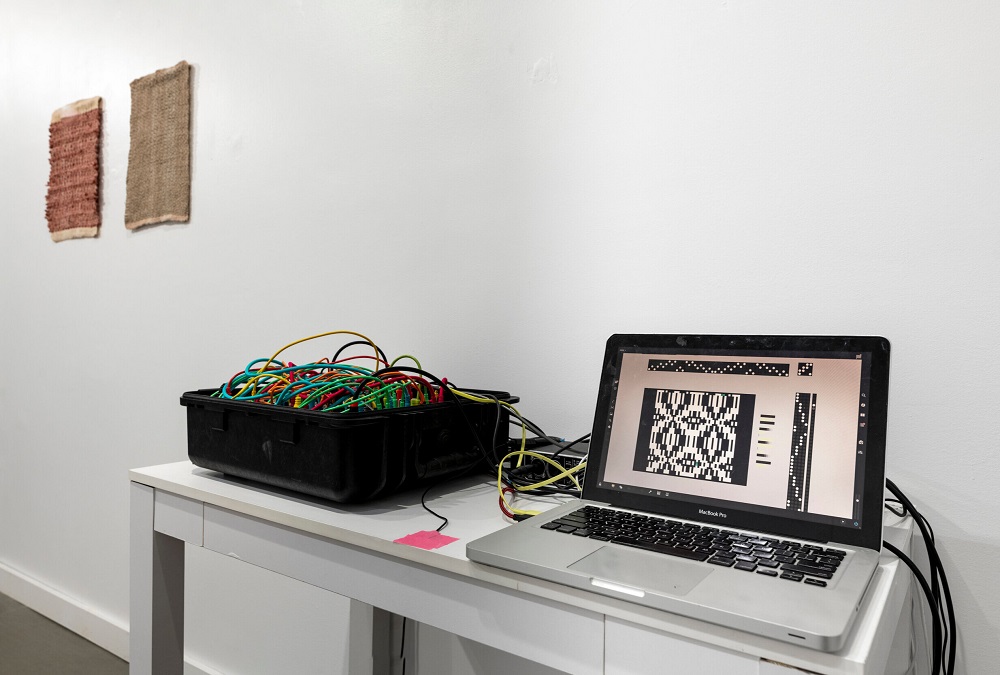

Back to Bockrath and draft/ patch/ weave: in January of 2021, Bockrath and Weinberg exhibited their work as part of an artist residency at Tiger Strikes Asteroid, a gallery in Philadelphia. Better yet (says the musicologist): they performed it. “We liked the idea of putting the process out in the open, and letting it become visible in its entirety,” Bockrath answered when I asked about the impetus behind this artistic decision. “The program we built operated in real-time, so we wanted to try using it for what it was capable of. We wanted to showcase the decision-making process and all it entails—our communication, materials, movements, senses.” In a video taken at one of their TSA performances, we see Bockrath at her loom, Weinberg bent over a table of computers and cords. We hear “the loom” translated through the Max/MSP patch, the loom’s sounds captured in the moment Bockrath began weaving, and the loom as it clacks and rattles with each pass of the shuttle. Even when the artists weren’t on site to perform in real time, they ensured that sound played a central role in any experience of draft/ patch/ weave. Audiences were given a program with a QR code that allowed them to listen to the associated sound compositions as they viewed the weavings on the walls, and provided access to a collection of weaving drafts featured in the exhibit. “We are interested in how these weaving drafts can be explored further in various media,” Bockrath told me, “whether by us or by the visitors who now also possess them.” Collected, researched, catalogued, and soon to be sung by a new set of weavers.

Notes

Banner photo caption: Weavings by Anna Bockrath, L to R: Windows, Twill, Honeycomb

My thanks to Anna Bockrath for her willingness to talk with me over email about draft/ patch/ weave. For more of Anna’s art, visit her website and Instagram.

For more on Eliza Calvert Hall and textile collectors, see: Phillis Alvic, “Eliza Calvert Hall, A Book of Hand-Woven Coverlets, and Collecting Coverlet Patterns in Early Twentieth Century Appalachia,” The Social Fabric: Deep Local to Pan Global; Proceedings of the Textile Society of America 16th Biennial Symposium. Presented at Vancouver, BC, Canada; September 19-23, 2018. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/