In Part 1 of this post I proposed that despite the color line that separated them in life and their receptions, Margaret Bonds (1913-72) and Edna St. Vincent Millay (1892-1950) were kindred spirits in feminist song. Here, I focus on a song cycle by Bonds that takes Millay’s rewriting of the myth of the “woman in love” one step further. I suggest that Bonds used the concept and narrative example of Millay’s 1931 sonnet sequence Fatal Interview to create a song cycle that musically and poetically affirms the autonomy of Woman’s self and depicts the emancipating rebirth of female identity.

On Millay’s Fatal Interview

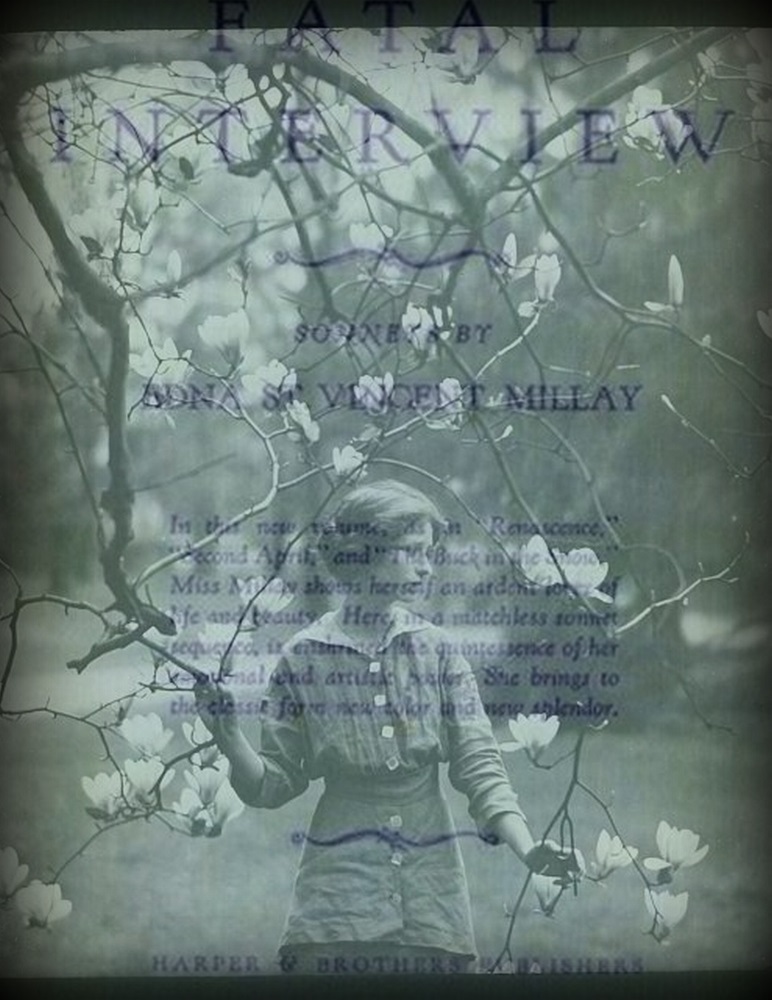

Millay’s Fatal Interview (1931) is a sequence of fifty-two sonnets whose title alludes to John Donne’s Elegy XVI: On His Mistris (“By our first strange and fatall interview, / By all desires which thereof did ensue”). That allusion is at least somewhat autobiographical, inspired by Millay’s affair with poet George Dillon (1906-68). The sequence’s first and last sonnets are a frame that likens Millay’s poetic characters to Selene and Endymion in Greek mythology. The intervening fifty sonnets chronicle the awakening and demise of a romantic relationship – the transformation of passionate, intensely sexual love into lasting anguish because of the lover’s unresponsiveness. Ultimately, the poet realizes that however much she might crave his love, she does not need it. She moves on by affirming her own self and self-worth: he is mortal, and if he should find himself, “When faint at heart or fallen on hungry days, / Or full of griefs and little if at all, / from them distracted by delights or praise,” then he should take pride in the knowledge that she, a goddess, once loved him: “Indeed I think this memory, even then, / Must raise you high among the run of men.”

Although Fatal Interview has never acquired the iconic stature of The Harp-Weaver and Other Poems (1923), and some criticized Millay for writing love poems in a time of economic crisis and widespread despair, even those voices admitted its greatness. One, the redoubtable Harriet Monroe (1860-1936), declared it “a work of perfect art,” “one of the finest love-sequences in the language,” an “imperishable treasure” (220-21).

From Millay’s Sonnet-Sequence to Bonds’s Song Cycle

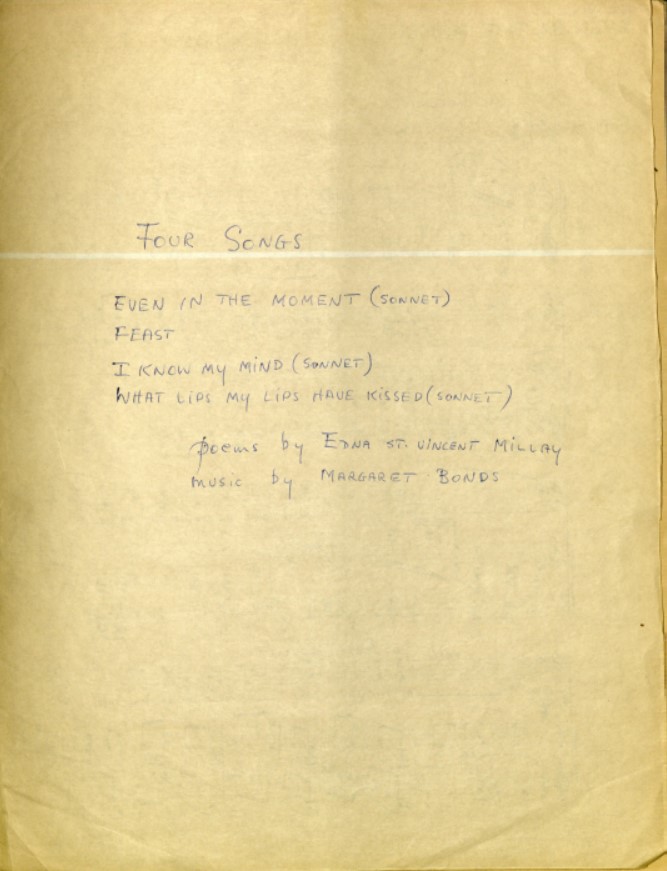

Out of this concept, Margaret Bonds fashioned a song cycle of her own. According to Bonds’s autograph inventory on the cover sheet that now houses the cycle’s first song, it begins with “Even in the Moment of Our Earliest Kiss” from Fatal Interview (XLVI), proceeds to “Feast” (from The Harp-Weaver and Other Poems), returns to Fatal Interview for the bold “I Know My Mind and I Have Made My Choice” (XLV), and closes on a note both sensual and melancholy with “What Lips My Lips Have Kissed” (also from The Harp-Weaver and Other Poems). The parallels to Fatal Interview are striking. In both, the female protagonist begins by reflecting sensually on her lover even as she concedes that she knew from the start that the relationship could not last. In both, initially intense sexuality turns to frustration born of the lover’s unresponsiveness and awareness of the relationship’s inevitable demise. In both, that recognition leads the lyric persona to reclaim her own identity independent of any lover. In both, the cycle closes with melancholy expressed through imagery of desolation. And finally, both are frame stories: in Millay’s sequence, the frame is the myth of Selene and Endymion, and in Bonds’s cycle it is the intimate and powerfully sexual image of the kiss (“our earliest kiss” in the first song; “what lips my lips have kissed” in the last).

Bonds’s Music

Bonds’s music is a masterfully insightful musical interpretation of Millay’s texts – at turns agitated, lyrical, angry, haunted, triumphant, sensual. The first song, “Even in the Moment of Our Earliest Kiss” (designated à volonté [willfully]), translates the poem’s searching conflictedness into searching chromatic ascents and deeply unsettled harmonies: though nominally in A minor, it contains not a single cadence in that key. The second song, “Feast,” is unrelentingly dissonant, almost atonal, as the persona realizes that satisfaction is not to be hers – that, for her, thirst is more satisfying than any “wine” or “fruit” will ever be, and thus resolves: “Feed the grape and the bean / to the vintner and monger; / I will lie down lean / with my thirst and my hunger.” (Bonds emphasizes that dramatic assertion of the persona’s Self by setting the I in “I will lie down lean” as a high B natural, fortissimo, over furiously chromatic and agitated figures in the accompaniment.) In the third song she addresses her lover and declares that

I know my mind and I have made my choice;

Not from your temper does my doom depend;

Love me or love me not, you have no voice

In this, that is my portion to the end.

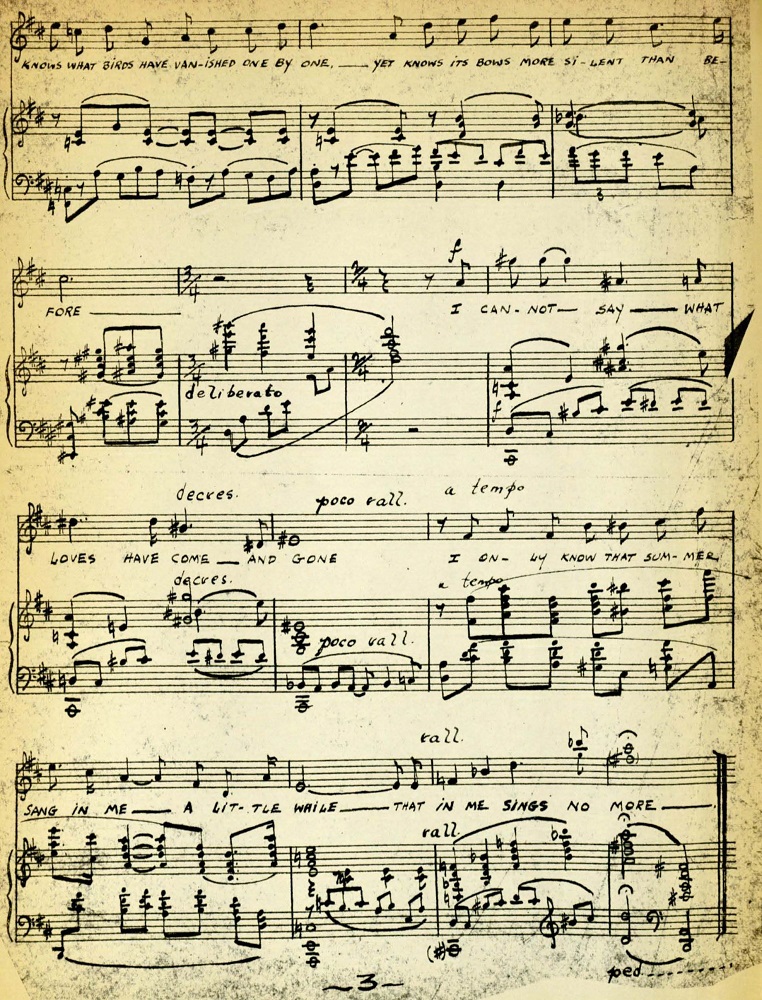

Here, the wandering harmonies are replaced by an assertive D minor, designated “baldamente con agitamento” (boldly, with agitation). And, this resolution accomplished, the final song turns to D major, “Andantino – tenerezza” (somewhat slowly – tenderness). Here the frustration, anger, and bitterness are gone; what’s left is the persona’s melancholy acceptance, and her embracing of her own, authentic identity, expressed in sinuous, graceful lines and exquisitely sensual beauty.

Bonds’s Ending

And there is one more thing – a twist by which Bonds adds her own individual interpretation to Millay’s concept: whereas Millay’s Fatal Interview ends with residual anger and disdain born of the affair’s demise, Bonds’s does not. Instead, Bonds’s music leaves those emotions behind, so that what negativity remains is vestigial only. This is evident in the evolution of the four songs’ harmonic language and the cycle’s tonal structure, where the opening A minor eventually resolves to a D-minor/D-major pair whose keys symbolize the protagonist’s victory in converting her hope for a lasting relationship into self-reliance and a rebirth of her female identity. The conclusion of Bonds’s Four Songs is not cold, but embracing and accepting, warm and beautiful. The last song’s closing bars make this abundantly clear – for as the persona declares that “I only know that summer sang in me / A little while, that in me sings no more,” the melodic line unfolds to span a thirteenth as it soars from d1 to b flat2 – a glimpse, perhaps, of the expansive and magical beauty that comes with the rebirth of female identity freely claimed.

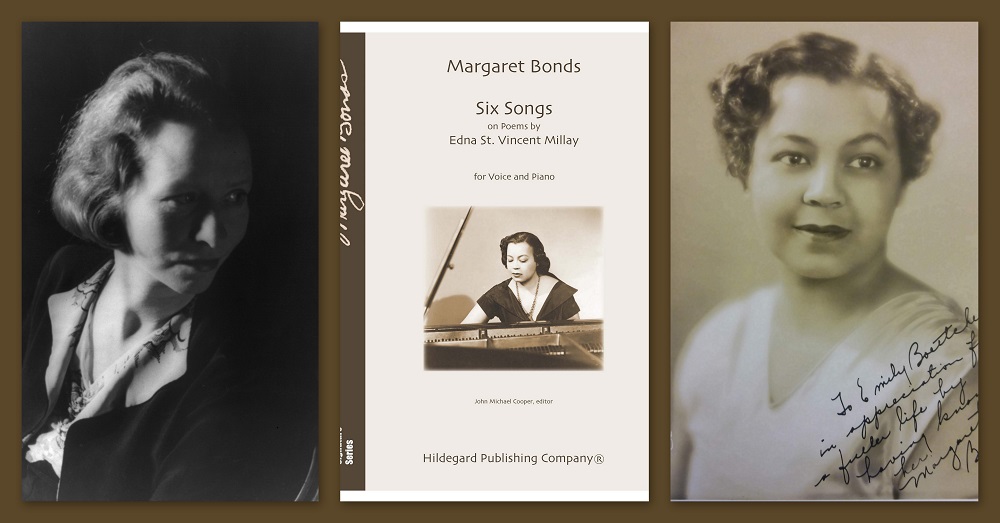

Bonds’s six settings of poems by Millay are all published in my source-critical edition by Hildegard Publishing Company, and the four songs discussed in this post are also available (though not presented as a cycle) in another edition by Louise Toppin. Dana Zenobi has performed the Four Songs separately Here is the world-premiere performance of the Four Songs as a cycle, given by soprano Katerina Burton with pianist Michelle Papenfuss.

Notes and Acknowledgments

The songs are available from Hildegard Publishing Company in the original high keys and in a transposed version for medium voice.

Sources for this post include:

“H.M.” [Harriet Monroe], “Advance or Retreat?,” Poetry: A Magazine of Verse 38 (1931): 216-21.

The best summary of Fatal Interview as a whole is found in Norman A. Brittin, Edna St. Vincent Millay [Boston: Twayne, 1982], 85-90.

Special thanks to Charla Burlenda Wilson, Archivist for the Black Experience at Northwestern University; Holly Peppe, Literary Executor, millay.org; Katerina Burton, soprano; Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University; Booth Family Center for Special Collections, Georgetown University Libraries, Washington, D.C.

Guest Blogger: John Michael Cooper

I am Professor of Music at Southwestern University in Georgetown, Texas, and the main contributing editor of Hildegard Publishing Company’s Margaret Bonds Signature Series, which is currently slated to include thirty-four more editions of previously unpublished music. I have also edited and published sixty previously unpublished works by Florence B. Price (G. Schirmer). I am currently working on a book titled Margaret Bonds: “The Montgomery Variations” and Du Bois “Credo” for the New Cambridge Music Handbooks Series (forthcoming, 2022). You can learn more about me here.