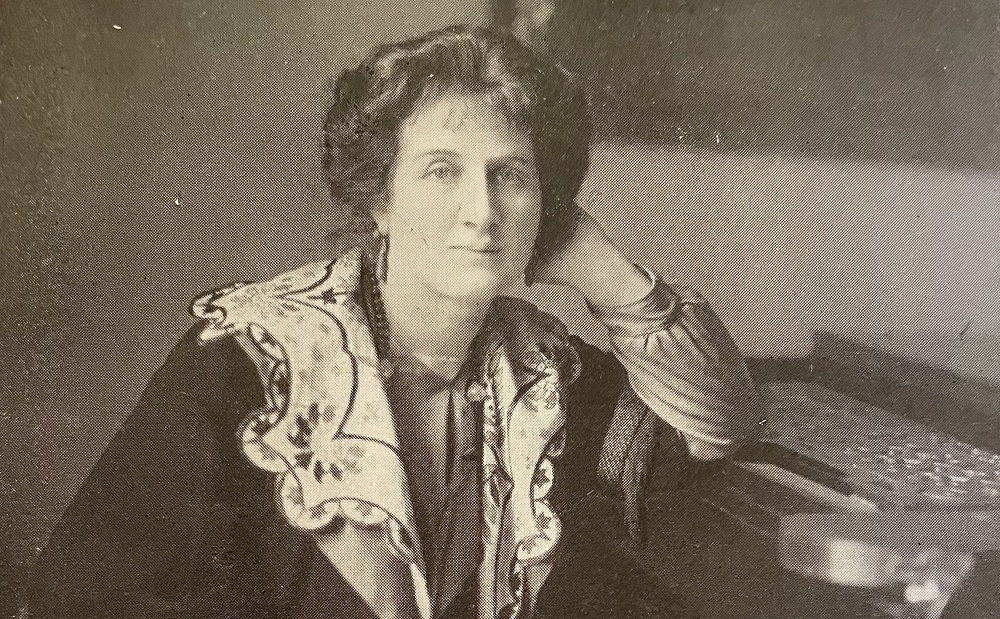

We have both been struck by the extraordinary beauty of Liza Lehmann’s setting of the poem “Evensong,” by Constance Morgan. In this joint post, we converse about the song.

Christopher Reynolds

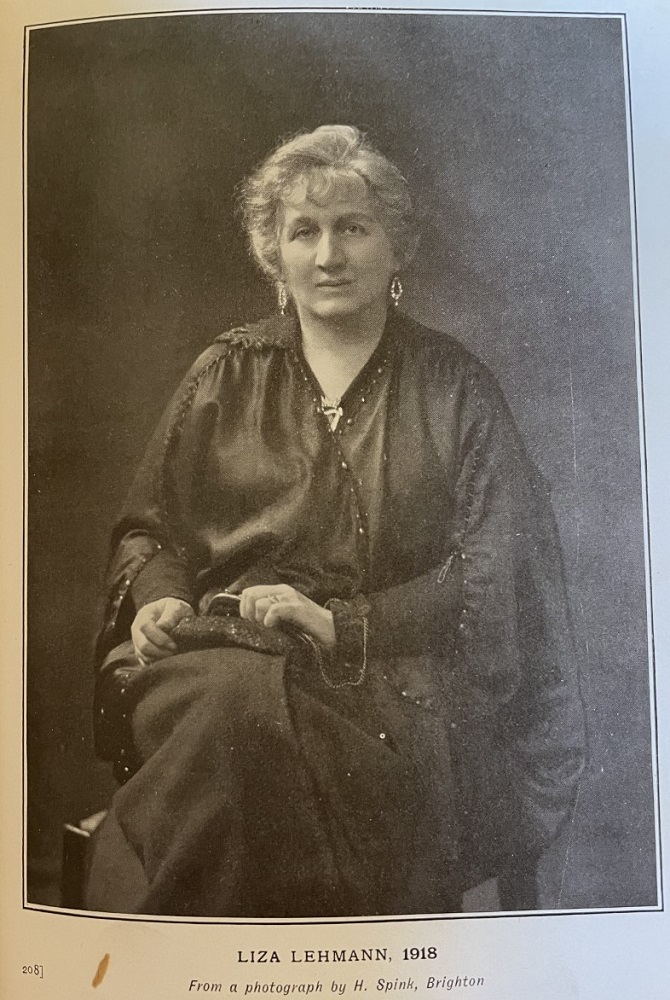

First, some context: Liza Lehmann (1862–1918) was by far the most prolific and distinguished woman song composer of her generation, having published approximately 370 songs. She was the daughter of the eminent painter Rudolf Lehmann and the composer/arranger Amelia Chambers (A. L. Lehmann), the granddaughter of the wealthy Scottish writer and publisher Robert Chambers, and the wife of Herbert Bedford, composer, painter, and inventor. Liza Lehmann was acclaimed as a singer, pianist, and composer. Little is known about her poet, Constance Morgan, except that she published a slender volume of poems with Elkin in 1911, The Song of a Tramp, and Other Poems, and that Teresa del Riego set her poem, “Within My Garden,” in 1913.

Here is the poem:

Fold your white wings, dear Angels,

Fold your white wings;

Dew falls and the nightingale softly now sings.

—

Across the lawn lie shadows,

So still, so deep,

Dear loving Angels, pass not by,

Hush me to sleep.

—

Night falls, and whisp’ring goes the wind

Along the sea;

Fold your white wings, dear Angels,

Fold them, dear Angels,

Fold them round me.

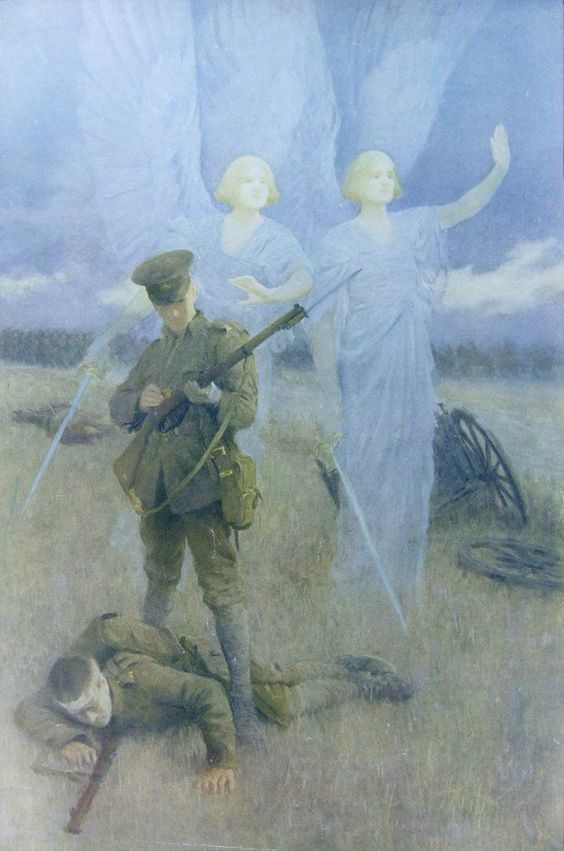

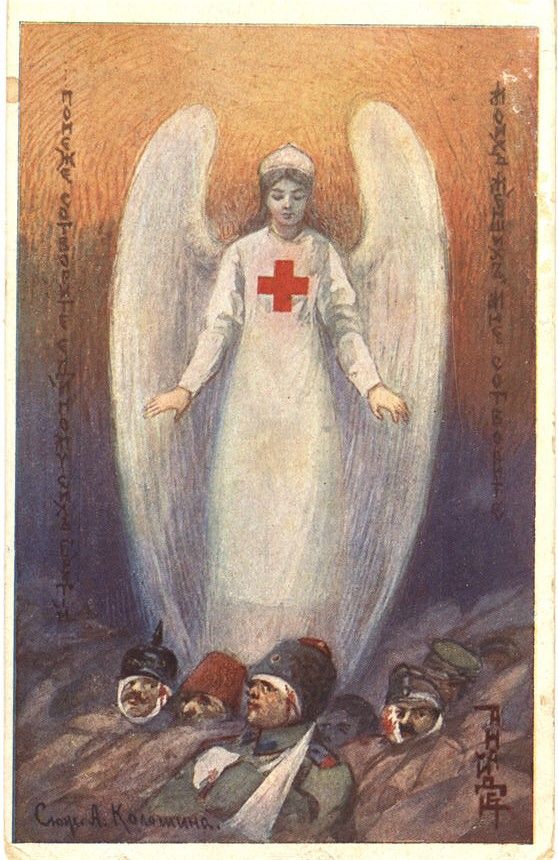

Since Lehmann published her song sometime in the second half of 1916 (it was copyrighted in the U.S. on 27 October), it needs to be interpreted in the context of WWI. What does the nightingale symbolize? Traditionally it is a symbol of love, but to all who knew Keats’s Ode to a Nightingale, it was also a symbol of man’s mortality. Together with the repetitive exhortations to angels to fold their white wings, which begin and end the poem, this seems to me a song about death. Angels are there to comfort the fallen, and since the start of the war they were thought of as comforters but also protectors in battle, in Germany as well as in the United Kingdom. This was particularly true after the Battle of Mons (August 1914), when angels were widely credited with miraculously saving the lives of British troops who were badly outnumbered by the Germans. In 1915 clergy throughout the United Kingdom preached sermons on the Angels of Mons. Postcards, such as these two, spread images of these angelic protectors.

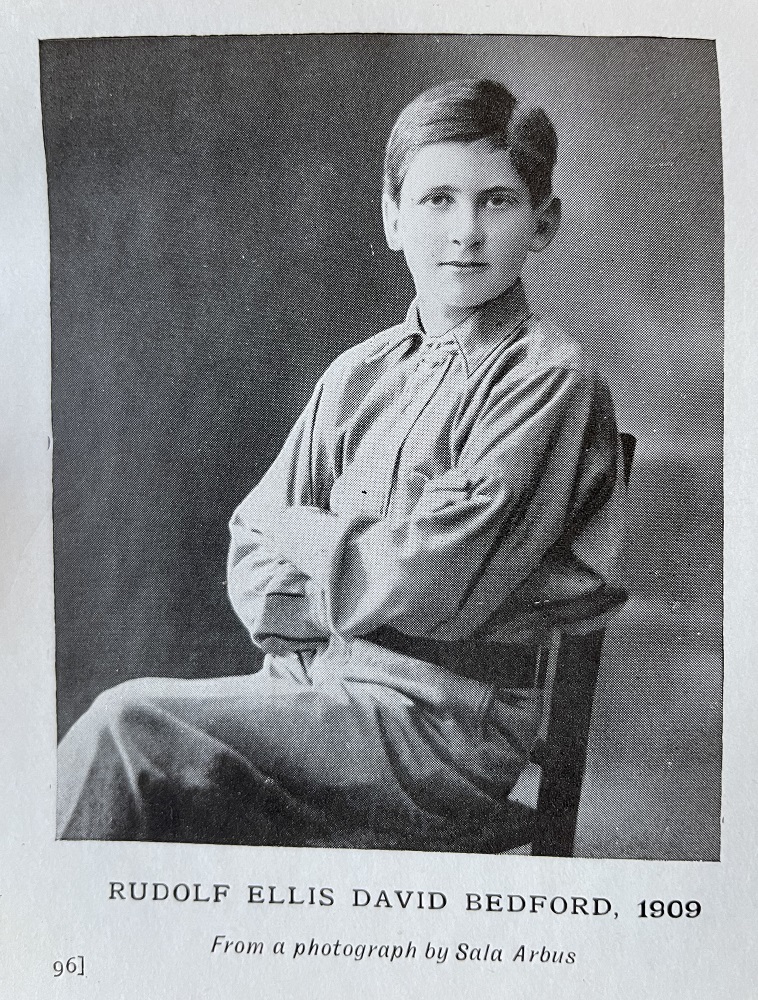

But the power of “Evensong” likely grows out of the most painful event in Lehmann’s life: the unnecessary death of her son Rudolf Ellis David (“Rudie”) Bedford while training at the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich. In her autobiography, The Life of Liza Lehmann, published posthumously in 1919, she describes him getting sick in late February, foolishly continuing to work, and then returning home on leave, gravely ill. He died of pneumonia one week later on 12 March 1916, a month short of turning nineteen. The singer asks the angels to “comfort me,” the prayer not of someone asking for protection for a soldier in some distant field of battle, but of someone at home in her own bed.

Stephen Rodgers

Knowing this context—that this song isn’t just about a sleepy evening—changes how I hear it, and makes me marvel even more at its subtlety and sophistication. I’ve long been struck by the sweetness of the song, but now I’m drawn to its bittersweetness. I notice not just the comforting diatonic harmony, the gentle melodic arcs, and the overall sense of ease, but also the touches of poignancy. In the first three measures, for example, the piano’s right hand rocks back and forth between D and a dissonant C (over a B-flat major chord). And after the first stanza (ending with “the nightingale softly now sings”), Lehmann inserts a short interlude in which the piano sings its own tune—the call of the nightingale—over the same B-flat chord with oscillating Ds and Cs; the main notes of this tune are also dissonances: C and G. How fitting that the song of the nightingale—this “symbol of man’s immortality,” as you put it—would sound a note of uncertainty and remain unresolved.

The same interlude returns in my favorite passage in the song. The music to the second stanza is identical to that of the first, but after “dear, loving angels, pass not by” Lehmann veers into another world. On “hush me to sleep” she settles onto an A-major chord—a major triad that lies a half step below the tonic B-flat major—and hovers there as the piano plays the same interlude tune we heard earlier, before transitioning back to the tonic. It’s a magical moment and, in light of the WWI context, a heartrending one. The key of A major is paradoxically near to B-flat major and far from it—a mere half-step away on a keyboard but on the other side of a circle of fifths. What better key to represent that land of sleep where the poetic speaker is about to be taken, and also the land of eternal sleep where Lehmann’s son was taken?

CR: I have a different favorite moment, Steve, which comes just a few bars after yours, at the start of the third verse. The verse begins—“Night falls”—and then the music slows down and pauses. Lehmann actually writes a fermata into the piano’s line. How extraordinary to write a pause into the beginning of a phrase; what a brilliant evocation of night falling, as if the arrival of darkness brings the cares of the world to a brief halt. I have listened over and over and it gets me every time.

SR: Musically, the fermata also underscores the instant when the rocking motion, the oscillating D-C notes, resolves down to B-flat. The release of that pent-up tension is part of the power you react to. On another matter, what do you think the title “Evensong” contributes to the meaning of the song?

CR: This evensong is not the popular Anglican church service but the end of a day, the church is not a building but a yard with shadows falling, the singers not robed choirboys but a solitary nightingale. It portrays a nightly occurrence in the natural world as something sacred. One final thought: it’s worth noting that Liza Lehmann Bedford outlived Rudie by only two-and-a-half years, dying in 1918 at the age of fifty-six on 19 September, seven weeks before the war ended. In her last days she put the finishing touches on her autobiography, writing the dedication:

To my darling son Rudolf, My hope in heaven,

And to my darling son Leslie, My joy on earth,

I dedicate these pages.

L. L. / September 1918.

Postscript: The full name of the pianist in this beautiful recording is Steuart John Rudolf Bedford. He is one of Liza Lehmann’s illustrious grandsons. Born in 1939, he died on 15 February 2021.

Notes and Credits

We are surprised to realize that this is the fifth WSF post to discuss songs that mark the death of children. See the earlier posts of Nicole Panizza, Verica Grmusa, Marian Wilson Kimber, and Stephen Rodgers.

Banner photo caption: Photograph of Liza Lehmann from 1913, taken by Violet K. Blaiklock, published in Liza Lehmann, The Life of Liza Lehmann (London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1919), facing pg. 130, cropped.