We called her Black Angel, Madonna, a legend of her time. No one sang like Ewa Demarczyk, we said. Not in Poland, not in the world. Not in the 60s and 70s. For us there was no one like her.

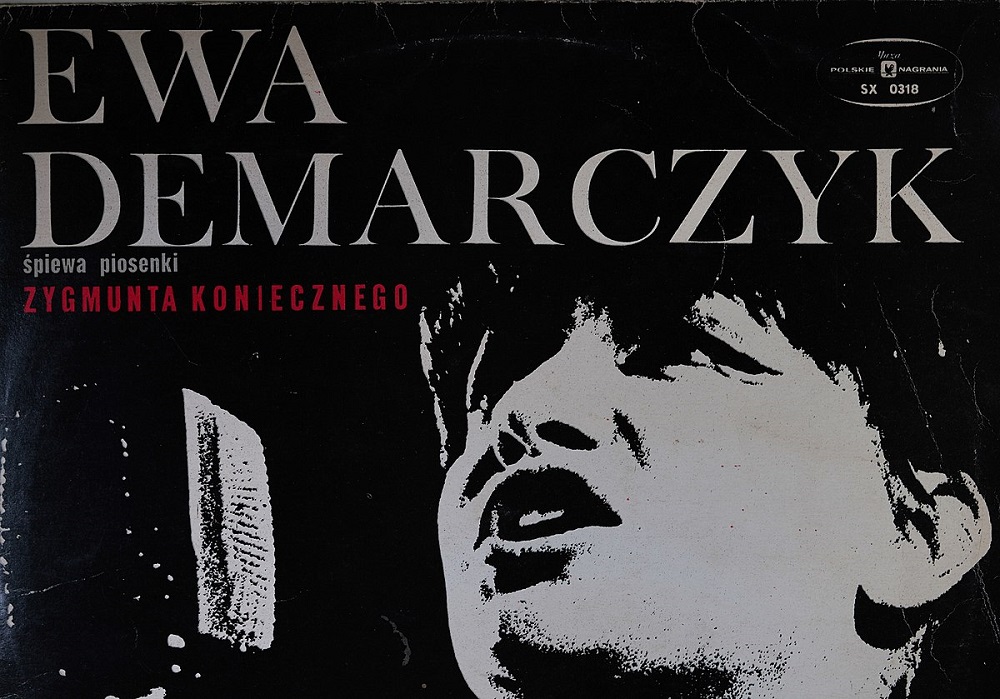

We began hearing of her in 1962, when she joined the legendary Kraków cabaret, Piwnica pod Baranami, loved for its subversive mixture of laughter and magic. Soon the songs she sang there—each an intense musical and poetic masterpiece—found their way to music festivals and radio programs. Then came prestigious awards, in Opole, in Sopot, followed by concerts abroad. Two years after her cabaret debut, Ewa Demarczyk and her then collaborator, composer Zygmunt Konieczny performed in filled-up theatres and sold-out concert halls.

Demarczyk sang poetry, the poems we knew by heart and the poems we would search for when the song ended. She sang with absolute precision and striking power, though her powerful, commanding voice was not her only talent. For Demarczyk was also a mesmerizing actress. With her motionless face, her ascetic gestures, and her piercing stare she seemed all-seeing, otherworldly; a temple priestess, conjuring up her ghostly visions. Here is one of her early songs that she sang at the 1963 National Festival of Polish Song in Opole.

I went to Ewa Demarczyk’s concert in person sometime in the early 70s, and the evening is still vivid in my memory. A dark stage, a black piano, a single microphone lit by a beam of light. A small figure in a simple black dress emerges out of darkness. Her black hair is shoulder long; her eyes contoured with kohl. She bends towards the microphone and waits for the music to begin.

She sings her most famous songs, music composed to the lyrics of poets popular in Poland before and after the war: the poetry of Tuwim, Leśmian, Pawlikowska-Jasnorzewska, Baczyński and Białoszewski. She enunciates the words with absolute precision, sometimes faster than my thoughts can follow. Her voice goes from whisper to scream, from recitation to most tender melody. She is not always faithful to one specific poem. She aims at the poet’s vision, its very essence. Song after song conjures up images that stay with me until now. A whirling carousel with wooden madonnas at a village fair; a Gypsy woman on a messed-up tavern bed asking for anything, a shawl, a kerchief; Rebeka in a far-away shtetel which no longer exists mourning her unrequited love; a hunchback who, on his crooked shoulders, drags the weight of his broken life:

Demarczyk did not just sing Polish poetry. She also sang the poems of Goethe, Mandelstam, Rilke. She didn’t just sing in Poland; she also sang in Germany, Belgium, Switzerland, Sweden, Italy, Cuba, Mexico, Australia. She performed in the world’s most prestigious concert halls, including the Olympia in Paris, Carnegie Hall in New York, the Chicago Theatre, Queen Elizabeth Hall in London and Theatre Cocoon in Tokyo. They loved her wherever she went, but for us, the post-war generation, Ewa Demarczyk was far more than a beloved singer.

For me, growing up in Poland meant growing up on the ruins of World War II. It meant walking in the streets lined with half burnt houses, exposing what had once been apartments of those who had been killed or fled. It meant living with silence, uneasy and heavy and ubiquitous. Our parents and grandparents did not speak of the war, of the Holocaust, of the destruction and humiliating defeat. They said we would not understand. They said no one who did not live through these years ever would.

It was this heavy, ever-present silence that Ewa Demarczyk broke.

She sang of the fields of fire; she sang of the ruins and loss; she sang of mourning and of hope. She was fire. She was water. She was poetry and song and music combined.

She had found the means to express all that was unsaid.

She sang and we listened, breathless, spellbound, our hearts speeding up.

Notes

The Polish portal Culture.pl carries an extensive discussion in English and Polish of Ewa Demarczyk’s life and art.

The banner photo was taken by Marek Andrzej Karewicz in 1967 and is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

Guest Blogger: Eva Stachniak

Eva Stachniak is an award-winning and internationally bestselling author of five novels. The Winter Palace was The Globe and Mail Best Book of the Year and made The Washington Post’s most notable fiction list in 2012. Born and raised in Poland, she moved to Canada in 1981 and lives in Toronto. Her latest novel, The Chosen Maiden, tells the story of Bronia Nijinska, for whom her brother, Vaslav Nijinsky, created the role of the Chosen Maiden in Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring. The novel has been published in Canada, the US, Germany, Poland, Italy and, most recently, China. For more, see her website.