Mary Turner Salter’s song, “The Cry of Rachel,” published in 1905, was widely popular in the first decades of the century (a score is available). Salter, a former singer, was a sensitive and prolific song composer. Her 137 songs rank her output among the top women composers of English-language songs, according to an extensive database of songs published from 1890 to 1930. A setting of a poem by Lizette Woodworth Reese, “The Cry of Rachel” evokes the biblical lament of Rachel at Herod’s slaughter of boys under the age of two, in fulfillment of the prophecy of Jeremiah: “Rachel weeping for her children and she refused to be comforted, because they are no more” (Matthew 2:18). Yet Reese’s lyrics are not metaphorical, but intimate and personal. The voice of a desperate mother begs death to “let her in,” so that she might be reunited with her lost child. Salter’s heartrending song was taken up by female singers across America because of the ways in which it spoke to women’s experiences.

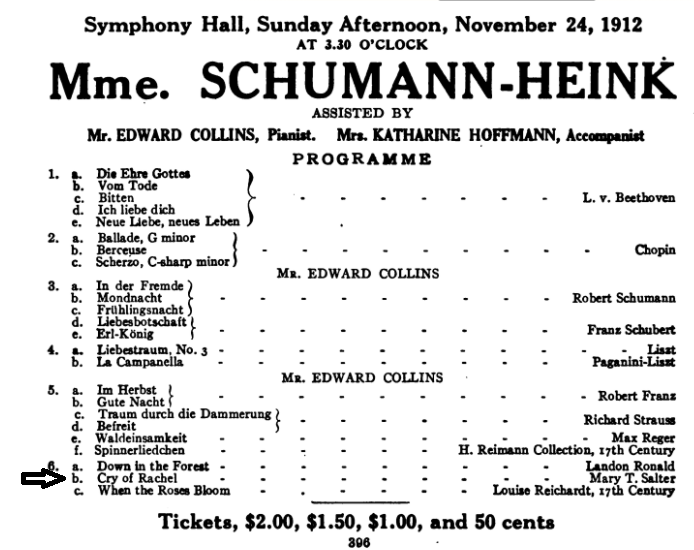

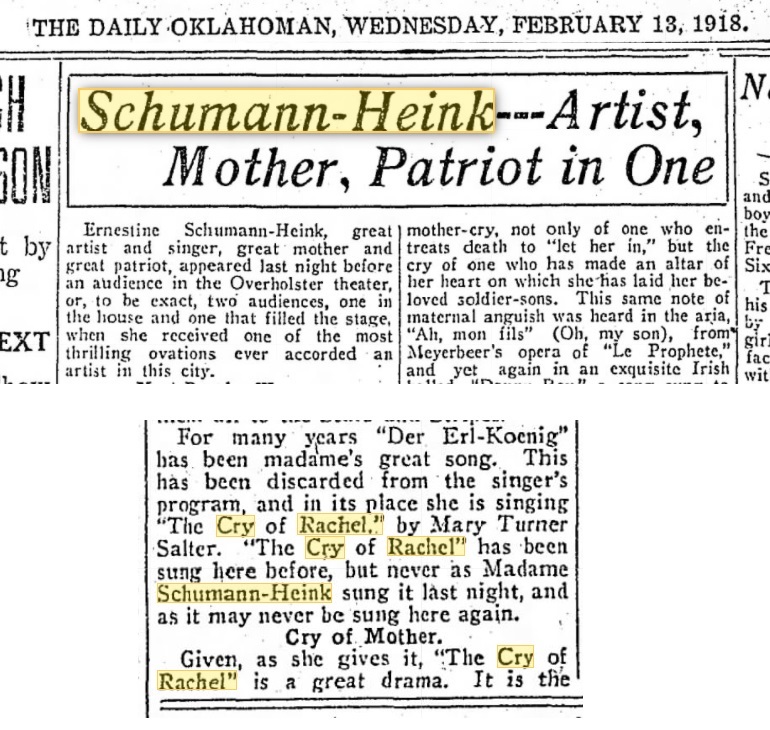

The prominence of “The Cry of Rachel” was due in part to opera singer Ernestine Schumann-Heink, who regularly featured it on her recital programs and recorded it for Victor in 1911 (her recording is available). Not only did the song appear on the programs of many professional singers, it was frequently sung by amateurs for the women’s clubs that dominated America’s musical landscape. Music publisher G. Schirmer continued to advertise it as a “favorite American song” as late as the 1930s. An annotated score owned by one president of the Iowa Federation of Music Clubs suggests that “The Cry of Rachel” became so familiar that it could be satirized. The copy’s additional penciled-in lyrics instead portray a husband begging his perpetually frowning wife to open a locked door. “Death, let me in,” becomes “Ma, let me in!”

Nonetheless, “The Cry of Rachel” has not fared well in later critical assessments. Judith Tick chose it to represent the “gross sentimentality” of women’s songs and suggested that Schumann-Heink had “drained the sob-bucket dry” (Tick, 117). J. B. Steane found the diva’s emotional recording of such “feeble music” embarrassing (Steane, 35). Yet audiences who heard Schumann-Heink perform Salter’s song were deeply moved. When the singer appeared in Fargo, North Dakota, in 1917, the reviewer felt she created a mood in the entire audience “which lasted several minutes. . . and could not be thrown off in an instant of time.” The writer for The Continent wrote “to hear Schumann-Heink sing ‘The Cry of Rachel’ was to feel that one has sounded with her the last and remotest depths of pathos in a human heart.” In Milwaukee in 1920, the audience was overcome with “waves of feeling too great for speech. . . As the last note . . . died away with its last anguished beseeching, ‘Death, let me in,’ one young woman in the audience swooned.”

Modern listeners may, like Tick, find the song overwrought. Yet a sentimental aesthetic dominated late nineteenth-century literature and music, and morbid poems about dead children made regular appearances in the period’s popular poetry anthologies. For example, in Eugene Field’s “Little Boy Blue” faithful toys gather dust waiting for their young owner to return, though he has long since been “awakened” by “an angel song.” The well-known poem was set to music by numerous composers, both male and female, including Ethelbert Nevin, Reginald de Koven, and Guy d’Hardelot. Reese’s poem is considerably less euphemistic than Field’s, and, set with an operatic atmosphere and declamatory entreaties, it becomes stark and powerful in comparison.

Mothers, Loss and Grief

Whether or not Mary Turner Salter’s own experiences with motherhood influenced her choice of text is unknown. The composer had five children, but in the autobiographical sketch published in 1939 after her death, she indicated only three were still living. Motherhood was famously central to Schumann-Heink’s publicity and promoted persona. Her devotion to supporting her eight children and stepson was presented as the motivation for her career, though when she performed “The Cry of Rachel,” her role as “The Nation’s Beloved Mother” on radio programs sponsored by a baby food company in the 1930s was still in the future. The singer lost two of her adult sons, one to illness and another in a German submarine during World War I. Even before their deaths, Schumann-Heink, the mother, reportedly threw herself into Salter’s dramatic song, “her eyes streaming.” Her husband wrote to Salter that her song taxed his wife as it “entirely gripped her vitality.”

Far more likely than identifying with Schumann-Heink’s maternal persona, audiences’ responses to “The Cry of Rachel” would have been shaped by their own experiences of loss and grief. Child mortality rates in America around the time Salter’s song became popular were more than one hundred per one thousand live births (Lindenmeyer, 59). The efforts of women organizers helped bring the problem to public consciousness and to transform the view of infant death as one of life’s inevitable tragedies. Working for babies’ survival was the first task of U.S. Children’s Bureau, founded one year after Schumann-Heink’s recording. With volunteer help from women’s clubs, the Bureau undertook regional studies to address the problem, and death rates dropped 24% between 1915 and 1924 (Bradbury, 8). Schumann-Heink’s many benefit performances included one in 1917 for La Mutualité Maternelle, a French organization similarly dedicated to reducing infant mortality.

“The Cry of Rachel” may also have expressed mothers’ anguish over grown children lost during World War I and the 1918 pandemic. German-born Schumann-Heink had become an American citizen, but her sons fought on both the German and the American sides. After the war, at one concert where she sang Salter’s song, she appeared holding white chrysanthemums tied in red, white, and blue ribbons, sent by “war mothers,” a symbol of their mutual sympathy. Causing even more deaths than the war, the influenza that swept the world in 1918 most often struck down young people in their twenties. Women who wept during “The Cry of Rachel” may have mourned their own losses, the song allowing them a small measure of cathartic release.

[See Marian Wilson Kimber’s previous post.]

Notes

Bradbury, Dorothy. Five Decades of Action for Children: a History of the Children’s Bureau. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, 1962.

Lindenmeyer, Kristie. “The U.S. Children’s Bureau and Infant Mortality in the Progressive Era.” The Journal of Education 177, no. 3 (1995): 57-69.

Steane, J. B. The Grand Tradition: Seventy Years of Singing on Record. 2nd ed. Portland, OR: Amadeus Press, 1993.

Tick, Judith. “Women as Professional Musicians in the United States, 1870-1900.” Anuario Interamericano de Investigacion Musical 9 (1973): 95-133.

The banner photo, The health of the child is the power of the nation, Children’s year, April 1918–April 1919, can be found in North Carolina Digital Collections and the Library of Congress.