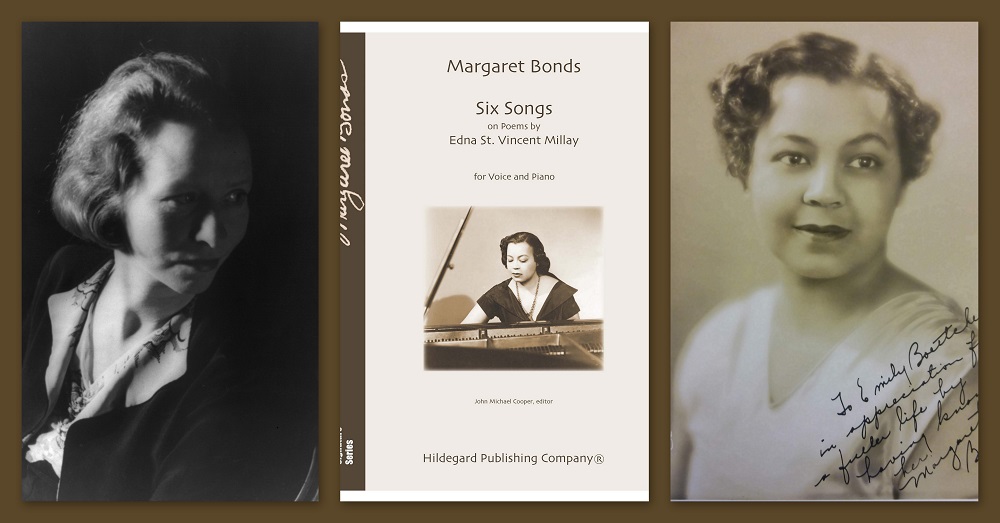

This post, the first of two, is occasioned by Hildegard Publishing Company’s publication of the world-premiere edition of Margaret Bonds’s complete songs on texts by Edna St. Vincent Millay. Part of the press’s Margaret Bonds Signature Series, the songs are available in the original high keys and in a transposed version for medium voice. The recordings used here are taken from both versions.

Despite the color line that separated them in life and in their posthumous receptions, Edna St. Vincent Millay (1892-1950) and Margaret Bonds (1913-72) were kindred spirits. And that kinship manifested itself in music.

Millay, a white woman, was born in Maine to a nurse and a schoolteacher. She was known from early on for her outspoken attitude, which created strains during her education at Vassar College (1913-17). She rocketed to fame when she won the 1923 Pulitzer Prize in poetry for her collection The Harp-Weaver and Other Poems. After 1927 the boldly feminist attitudes given voice in that volume were coupled with a pronounced sense of social justice and a view of poetry as a tool for “protest and resistance against the powerful forces of xenophobic paranoia and intolerance” (Newcomb 1995, 262). Nor was she a stranger to music. Her work is suffused with musical references, and she wrote the libretto for Deems Taylor’s opera The King’s Henchmen (1927).

The convergence of poetry and music in the life of a woman to act as agents for social justice applies no less to Margaret Bonds. Bonds was Black, born to a mother who was a musician and teacher and a father who was a doctor and noted author. She grew up on the south side of Chicago and earned her Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees in piano at Northwestern University. Her commitment to gender justice and racial justice manifested itself from the 1930s to the end of her career. And her letters and public statements make clear that her “Destiny” (upper-case D) as a woman and artist charged, by heritage, with working for social justice would not and could not be suppressed:

[My mother] believes in me. . . . She is willing to die with nothing [so] that I shall fulfill my Destiny. . . . She endures and accepts – for she sees – she knows – she knows that as there is the Sun, I shall win. . . . From my grandfather on down [my family] all worked silently, quietly, in obscurity for Mankind, for our oppressed Race. . . . [M]y grandmother, the child once removed from slavery, and my grandfather, the product of slaves and Indians – and my grandmother’s father – an Irish imigrant [sic] – a man of courage who came over in steerage, and made good – and my own father who has great intellect – and who would have been a great man had he not tried to conform to the taboos, inhibitions and the rest of them – these are my blood, my soul, I cannot help myself; this great desire to win. They all won before me and I must go farther. (Bonds 1942)

Their paths never crossed, Millay’s and Bonds’s. But given the parallels in their outlooks, is it surprising that Millay’s work eventually converged, artistically, with Bonds’s own? It is not – and the fruits of that convergence of kindred spirits are now coming to light with Hildegard Publishing Company’s release of Six Songs on Poems of Edna St. Vincent Millay. That collection of all Bonds’s completed Millay settings presents a four-song cycle plus two apparently independent songs. The latter are the subject of this post; the Four Songs will be discussed in Part 2.

The Two Independent Songs

“Hyacinth” and “Women Have Loved Before as I Love Now” are powerful, and strikingly different, expressions of Woman’s experience of love. Bonds brilliantly translates Millay’s texts into song by treating the poems’ imagery as a musical allegory for this experience. “Hyacinth” (“I am in love with him to whom a hyacinth is dearer / than I shall ever be dear”), published by Millay in 1923, is the aching contemplation of a woman’s unrequited love. It condemns expectations that women submit to sterile relationships and stick with men who care for them little or not at all. The poem’s central complaint that the poet’s lover lies awake at night, imagining he hears the teeth of field mice destroying his beloved hyacinths, but oblivious to the gnawing pain his obliviousness causes her, is realized, doloroso, in biting dissonances that depict her heartache. Bonds emphasizes the persona’s indignation at this obliviousness and resignation to its permanence via a powerful climax – “with anger” and fortissimo – at “he hears their narrow teeth at the bulbs of his hyacinths” and scornfully repeating “his hyacinths” followed by a protracted diminuendo, with continued dissonance, at “but the gnawing at my heart he does not hear.”

The posthumous premiere of “Hyacinth” was given on 26 February 2021 in this studio recording by soprano Dana Long Zenobi and pianist Catherine Bringerud of Butler University.

By contrast, “Women Have Loved Before as I Love Now” (first published in 1930) is a forceful affirmation of women’s right to choose their own loves – and to love assertively, boldly, passionately. Here, the dominant poetic image is that of the surging waves of “Irish waters by a Cornish prow / Or Trojan waters by a Spartan mast” and the blazing flames of “Love like a burning city in the breast” – images that Bonds translates into surging, widely voiced arpeggios in the accompaniment. That musical allegorization persists until the poet turns from discussing women “in lively chronicles of the past” to reflecting on herself. There, after a pause, Bonds adopts a declamatory style to observe that “in me alone survive / The unregen’rate passions of a day / When treacherous queens, with death upon the tread, / Heedless and wilful, took their knights to bed.”

“Women Have Loved Before as I Love Now” received its posthumous premiere on 23 February 2021 by mezzo-soprano Max Potter and pianist Timothy Accurso, as part of Opera Santa Barbara’s Noontime at Home series.

These two songs are isolated contemplations on Woman’s love. In the Four Songs (discussed in my next post), she penned a cycle that depicts the developing and awakening of her persona’s romantic consciousness.

Special thanks to Charla Burlenda Wilson, Archivist for the Black Experience at Northwestern University.

Bibliography

Margaret Bonds, Letter of December 17, 1942. Booth Family Center for Special Collections, Georgetown University Libraries, Washington, D.C. Shelfmark GTM-130530 Box 2, folder 3.

Edna St. Vincent Millay, “Three Sonnets.” Poetry: A Magazine of Verse 37 (1930): 1-3.

John Timberman Newcomb, “The Woman as Political Poet: Edna St. Vincent Millay and the Mid-Century Canon.” Criticism 37 (1995): 261-79.

Guest Blogger: John Michael Cooper

I am Professor of Music at Southwestern University in Georgetown, Texas, and the main contributing editor of Hildegard Publishing Company’s Margaret Bonds Signature Series, which is currently slated to include thirty-four more editions of previously unpublished music. I have also edited and published sixty previously unpublished works by Florence B. Price (G. Schirmer). I am currently working on a book titled Margaret Bonds: “The Montgomery Variations” and Du Bois “Credo” for the New Cambridge Music Handbooks Series (forthcoming, 2022). You can learn more about me here.