Around 1769, the French painter Jean-Honoré Fragonard made a portrait of Anne-Louise Boyvin d’Hardancourt Brillon de Jouy (1744–1821), a salon hostess, keyboardist, singer, and composer. Fragonard used his distinctively rough, sketchy brushstrokes to paint Brillon in an unguarded posture. A book lies open in front of her, and she seems ready to turn her back on us in a moment. Our eyes are drawn to the shadowy background of the painting, and it becomes clear what calls her away from our view: the book in front of her is a volume of music, and in the background stands her English “square piano.”

Madame Brillon owned at least one French harpsichord and one German piano in addition to this English instrument, but the English square was clearly her favorite. We know this not only from the fact that it appears in this sumptuous portrait, but also because the songs that she composed are filled with references to it. What she appreciated most about this instrument, it seems, was its grande pédale—the damper-raising pedal that alters the instrument’s timbre, making it resonant, blurry, ethereal. Many of Brillon’s songs, preserved in manuscript in the library of the American Philosophical Society and virtually unknown today, bear instructions to the pianist to apply the pedal generously, like this one: “accom.tavec la grande pédale et le plus doux possible” (accompanied with the great pedal and as softly as possible). When the music historian Charles Burney visited Madame Brillon in 1770 and heard her play and sing, he praised her in almost every respect, but he found her use of the pedal excessive: “I could not persuade Madame B. to play the piano forte with the stops on—c’est sec, she said—but with them off unless in arpeggios, nothing is distinct—’tis like the sound of bells, continual and confident.”

What was it about the English square piano—still a novelty in France—that Brillon valued so much? And why did her method of playing differ so drastically from Burney’s? I think the answer lies in the songs that she composed.

Madame Brillon’s Songs

Madame Brillon’s songs are romances—simple, melodious pieces that were meant to evoke an idyllic, pastoral world. Jean-Jacques Rousseau described the romance as possessing “a simple, touching style and a taste that is a little antique.” The pastoral was one of the most fashionable artistic tropes of eighteenth-century France. (Think of Queen Marie Antoinette playing milkmaid in the faux-pastoral village that she had built at Versailles.) Many upper-class men and women wrote poetry in the pastoral mode. Anthologies of these poems appeared in print, and some of these volumes included music—but often only with a melody line, and no accompaniment. If this seems surprising, Rousseau confirmed that it was normal: “any accompaniment from an instrument detracts from this [simple] impression. To sing a romance, nothing is required but a clear, correct voice, which pronounces well and which sings simply.”

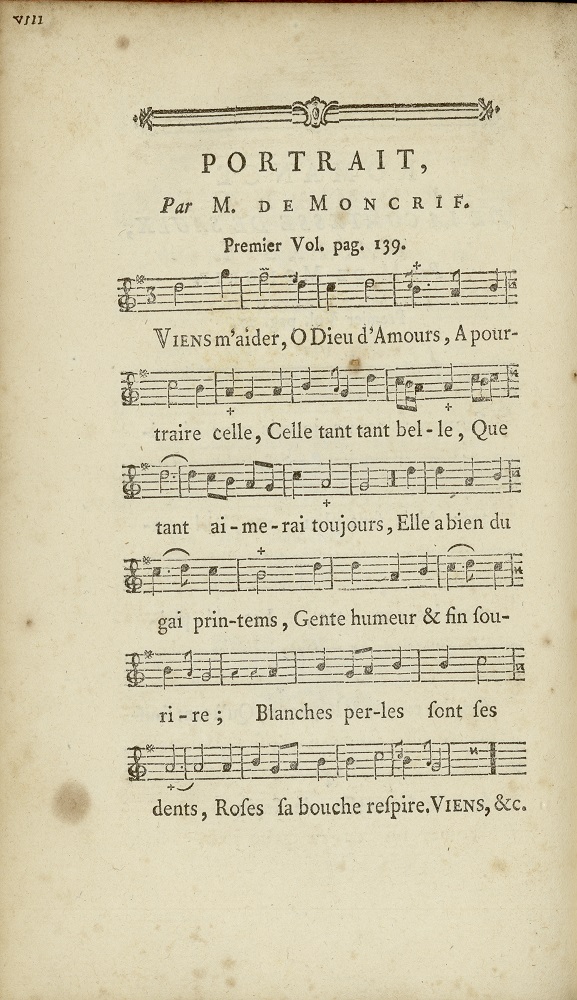

The famous poet François-Augustin Paradis de Moncrif was a master of the genre of the romance, and his poetry appeared in numerous printed anthologies. One of his most popular poems was “Viens m’aider o dieu d’amour” (Come, help me, oh god of love). In the Recueil de romances published by Charles de Lusse in 1774, the poem appears with two different musical settings, both monophonic. Here is one of them:

But Brillon was not content with a melody alone. She knew that, with her square piano, she could do more. In her songs, she used her piano to evoke the instruments of the pastoral landscape: especially the guitar and the harp. These were instruments of simplicity, instruments of nature. And, together with keyboard instruments, they also happened to be the instruments most available to women.

In fact, I think the harp served Brillon as a model for the piano parts in her songs. While most composers in the 1760s and ’70s wrote songs to be accompanied by a simple chordal accompaniment, Brillon wrote out full webs of arpeggios. Full arpeggiated patterns like this were common in harp music, but they were not typical of song accompaniments. While we don’t know the exact years when Brillon composed her songs, it appears that she was writing complex, fully written-out piano parts before her male contemporaries. (The first published songs with fully notated right-hand parts, rather than just a figured bass line, didn’t appear in France until around 1784.)

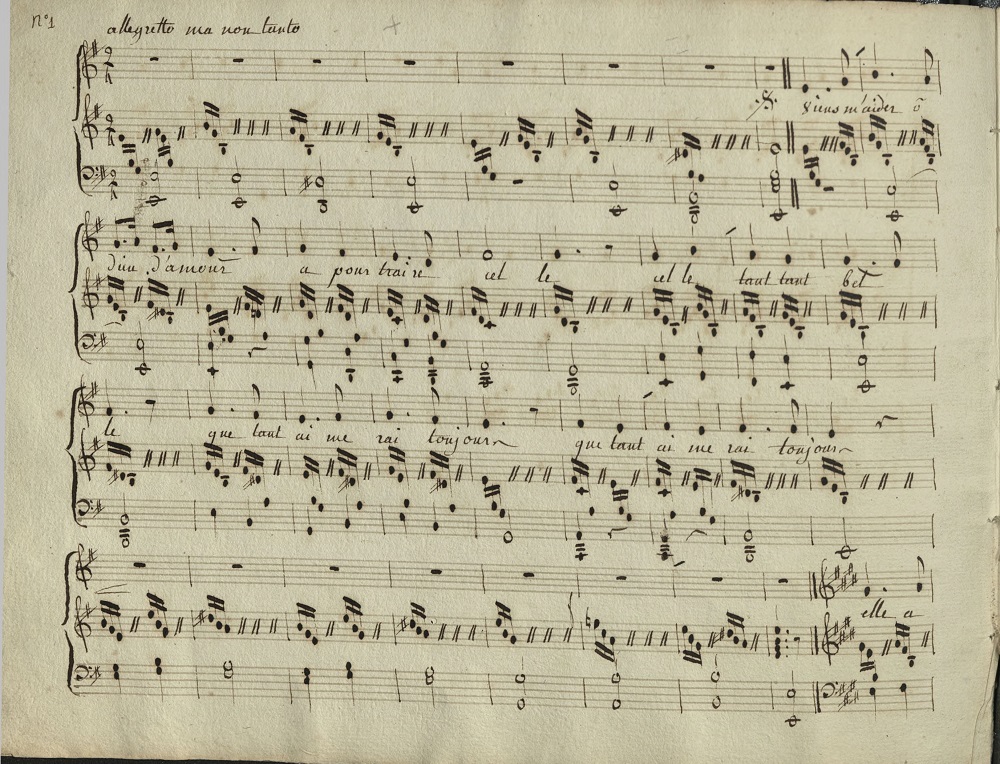

Brillon’s setting of “Viens m’aider o dieu d’amour” is a case in point. She writes a lush piano accompaniment to support the singer’s simple, touching melody. The voice part stays within an easy range, accessible to most singers. The top note of the piano’s figuration tracks the voice part almost throughout, helping the singer find the right notes, but the rich arpeggiated patterns mean that the piano never gets in the singer’s way.

Here is Madame Brillon’s setting of “Viens m’aider o dieu d’amour,” from the library of the American Philosophical Society, followed by a recording that I made with my friend, soprano Sonya Headlam:

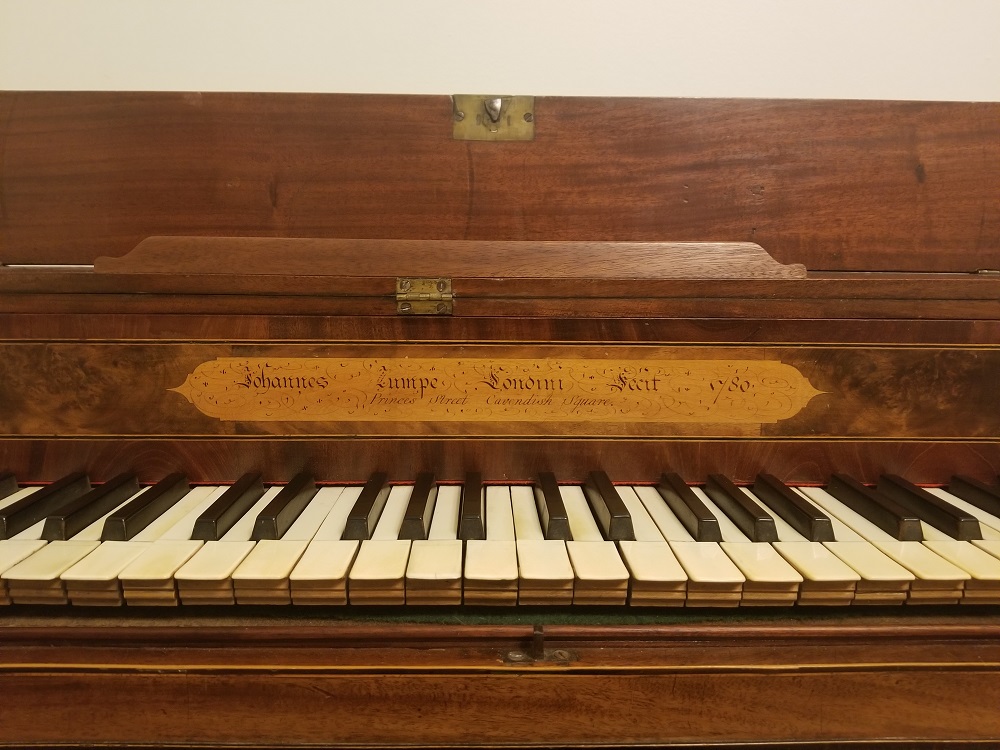

In this track from our forthcoming recording In the Salon of Madame Brillon (Acis, 2021), I’m playing an English square piano (pictured above) that must be nearly identical to the one that Madame Brillon owned. This is an original instrument from 1780 by the builder Johannes Zumpe, a German immigrant to England who popularized the English square piano. I’m fortunate enough to have this instrument on loan from Leslie Martin:

This instrument has opened for me a new understanding of Madame Brillon’s songs—and of her sound world. In the portrait by Fragonard, she appears poised to turn her back on us and devote her attention to her English square piano. She might accompany herself in song, or maybe one of her daughters will sing with her. Either way, I can understand why she is drawn to her instrument.

***

Here is the text to “Viens, m’aider o dieu d’amour,” along with an English translation by me together with Sonya Headlam:

Viens m’aider o dieu d’amour,

A poutraire celle,

Celle, tant, tant belle,

Que tant aimerai toujours.

Elle a bien du gai printemps

Gente humeur et fin sourire.

Blanches perles sont ses dents,

Roses sa bouche respire.

Come help me, oh god of love, / To portray this one, / This one, so, so beautiful, / Whom I will love so much always. / She has received from happy springtime / A gentle disposition and fine smile. / White pearls are her teeth, / Her mouth breathes roses.

Guest Blogger: Rebecca Cypess

I am a musicologist and historical keyboardist specializing in the history, interpretation, and performance practices of music in the 17th and 18th centuries. I have recently completed the book Women and Musical Salons in the Enlightenment (University of Chicago Press, 2022). The chapter on Madame Brillon will be complemented by the recording In the Salon of Madame Brillon, which I’ve made with the period-instrument group that I direct, the Raritan Players. I serve as Associate Dean for Academic Affairs at the Mason Gross School of the Arts, Rutgers University. You can learn more here.