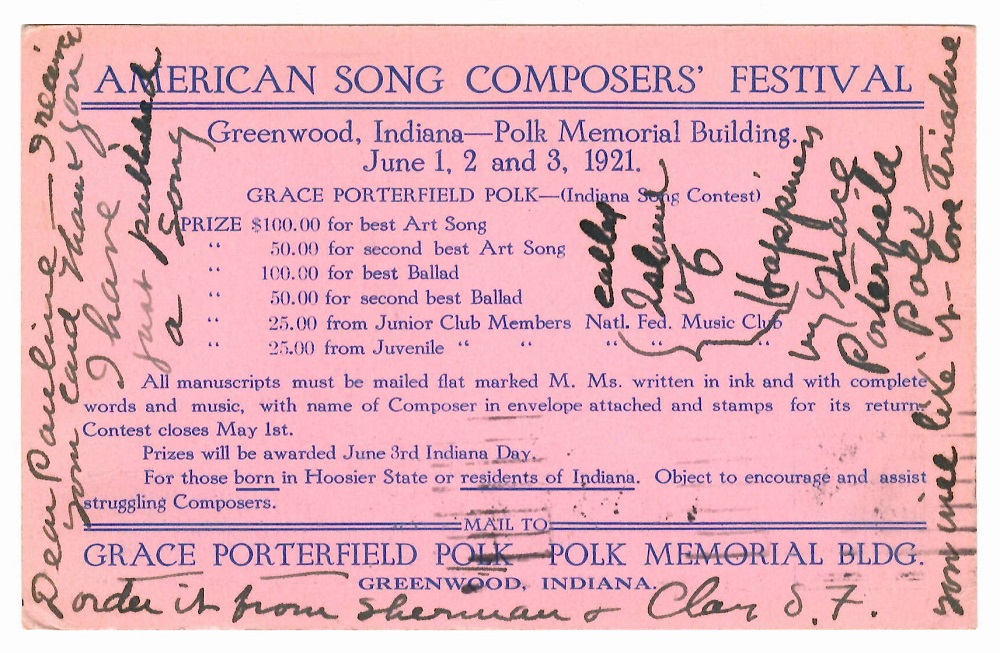

On a 1921 postcard, Ariadne Holmes Edwards announced to a friend in San Francisco that she had published a new song, Grace Porterfield Polk’s “Island of Happiness,” adding, “You will like it.” Edwards was a singer and composer, and she founded the Sherman Square Music Company to issue her songs and those of other women. The postcard across which she quickly scrawled her message did not promote her wares, but rather advertised the American Song Composers’ Festival. The Festival was the ambitious project of Polk, a resident of Greenwood, Indiana, the small town south of Indianapolis where the annual event was held.

When she was a young woman, Grace Porterfield (1875-1965) sang professionally for two years, over the strenuous objections of her mother. Grace married Ralph Polk, a respectable Indianapolis businessman, in 1903. Only one of their children, a son, survived. Polk took up composing songs, also writing the poetry that she set to music, as did Carrie Jacobs Bond, Clare Kummer, Caro Roma and many other women. Active in women’s organizations, she became the first head of the junior division of the National Federation of Music Clubs. But Grace had aspirations beyond club work for children and her own musical career.

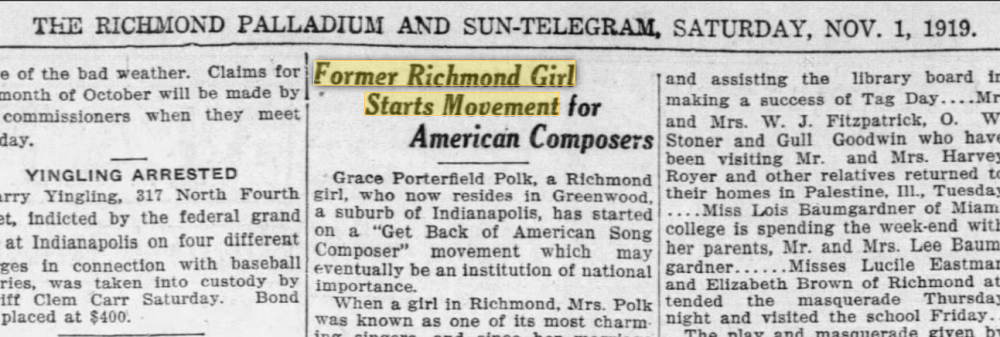

Polk’s husband had inherited a Greenwood canning company, the first cannery in America to can grapefruit. After the death of Grace’s father-in-law, the company’s founder, the Polk family donated a community center to the town. It featured meeting rooms, a library, a swimming pool, and the perfect space for concerts: an auditorium that held a thousand people. With additional support from her husband, the Polk Memorial Community Building was to play a central role in Grace’s musical campaign. The headline in Polk’s hometown Indiana newspaper boldly announced that “Former Richmond Girl Starts Movement for American Composers.”

In spite of her wealth, Polk indicated that her modest compositional career had not come easily, and she wondered, “how composers ever live through the struggles to achieve recognition when they really have to write music to keep the wolf from the door.” In 1920, The Writer reported that Polk wanted to “make it possible for young composers with high ideals to be in a position to work out those ideals.” Her plan was to organize a yearly music festival at Greenwood’s Community Building, bringing together leading and up-and-coming songwriters, as well as performers and publishers, for recitals and presentations. The 1921 event featured Geoffrey O’Hara, commercially successful composer of the hit song, “K-K-K-Katy,” then just three years old, and George Fischer, wealthy co-owner of New York City’s J. Fischer & Bro. music publishing house. Each festival culminated with generous financial prizes for the best songs; Polk received as many as 360 entries for consideration.

The song contest specifically encouraged Indiana composers, but Polk saw her strategy as a model for other states. She ultimately intended to “lay the foundations” for cooperative efforts by clubs all over the country. Her concerts in Greenwood were part of a larger post-World War I patriotic attempt by women’s music clubs to secure the musical development of American culture. During the 1920s, clubs frequently promoted the music of their own states. For example, Iowa clubwomen sponsored over a hundred Iowa composers’ events before World War II, and women’s clubs in Illinois, Michigan, and Oregon also promoted the music of their state’s composers. To an extent, we don’t yet fully realize, most work on behalf of “Americanization in music” was due to these regional groups and to national women’s club federations. In contrast, Polk intended, singlehandedly, to spur the development of American song – nationally.

Unfortunately, the festival at the center of Polk’s grand mission lasted only three years, from 1920 to 1922. Whether a small town in Indiana with a population of 1900 was not an attractive enough location to lure leading American composers, or whether Grace was simply unable to maintain the festival’s funding, is unknown. The Polks also had a house in Miami, which became their primary residence. Grace became musically active there as well, starting multiple clubs and offering prizes to Florida composers. But as the composer of songs entitled “Hoosier-land” and “Apple-Blossom Time in Indiana,” she didn’t fully leave Indiana behind.

Polk was later involved with the National League of American Pen Women, a professional group that included leading composers such as Amy Beach and Carrie Jacobs-Bond, two songwriters she had hoped to bring to Greenwood. Since the NLAPW also consisted of artists and writers, it was a perfect fit for the poet-composer, and Polk founded the organization’s Indianapolis chapter. She again donated prize money for songs by Pen Women and financed the hiring of musicians to play their compositions at a 1935 meeting in Miami. Polk also established a composition scholarship at Indiana University.

In the midst of her ongoing patronage of songs by other composers, Grace’s publication of her own music slowed considerably after the 1920s, though she indicated that most of her 200 songs were still in manuscript (approximately 21 appeared in print). She published a book of poetry in 1940, and her final collection of songs, My Garden of Music, appeared in 1964. The former Polk Building, home of her song festival, is now a refurbished office complex that contains an autism center and a wedding venue.

What became of Polk’s “Island of Happiness?” When she met Ernestine Schumann-Heink in Florida, the famous opera singer performed the song, and the composer dedicated it to her. Its sentimental lyrics describe how tender care will cultivate the flower of love. They are perhaps a fitting epitaph for Grace Porterfield Polk, who hoped to make American song bloom and grow.