The history of classical-music performance in the United States is rife with systemic racial exclusions—with a legacy of whites policing major performing arts institutions, venues, audiences, and artists. The details differed according to date and location. That legacy, in turn, contains many puzzles, as in the lifelong devotion of the African American contralto Marian Anderson to “O mio Fernando,” an aria from Donizetti’s opera La favorita. On the one hand, opera arias are basic to the repertory of singers in classical music, so Anderson’s allegiance makes total sense. On the other, she, together with gifted African American singers of her generation and earlier, were banned from major opera houses, including the Metropolitan Opera Company. In January 1955, in her late 50s, Anderson finally broke through the Met’s exclusions—which had amounted to Jim Crow policies—when she made a debut in Verdi’s Un ballo in maschera. In the process, she opened the door for other African American virtuosos, such as Mattiwilda Dobbs, Robert McFerrin, and Leontyne Price, to name only a few.

Yet despite the negative connotations that “O mio Fernando” might have represented for Anderson, it became one of her go-to numbers. She performed it across the country and around the world, often in highly visible and contested settings. She sang it over the radio. And she delivered all those performances knowing that the role of Leonora, a character caught in a love triangle, was off-limits. Asked by an interviewer decades later if she had been “anxious” in her youth to sing opera, Anderson responded: “Oh, yes, indeed. To come home from high school [in Philadelphia], we had to go under a railroad trestle and the trains would be rolling along. And I remember thinking, ‘Oh, if just one of these days I could be on a train with the Metropolitan Opera Company going somewhere.’ And I prayed to the evening star, and I prayed and I prayed. So I had dreamed about it for a very long time—from high school days through the better part of my career.”

Perhaps “O mio Fernando” helped sustain Anderson’s dreams. Perhaps it became a form of quiet protest—a way of proclaiming her virtuosity and talent within a repertory tenaciously policed as white. Perhaps it simply felt good in her voice and brought pleasure in performance.

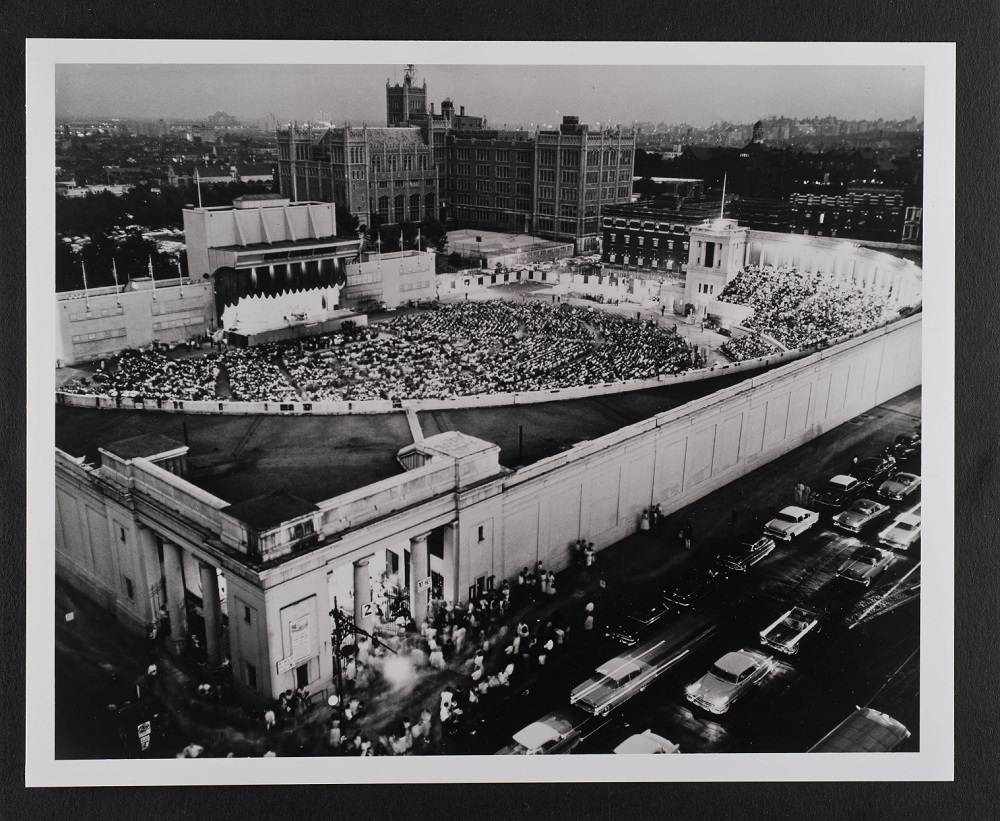

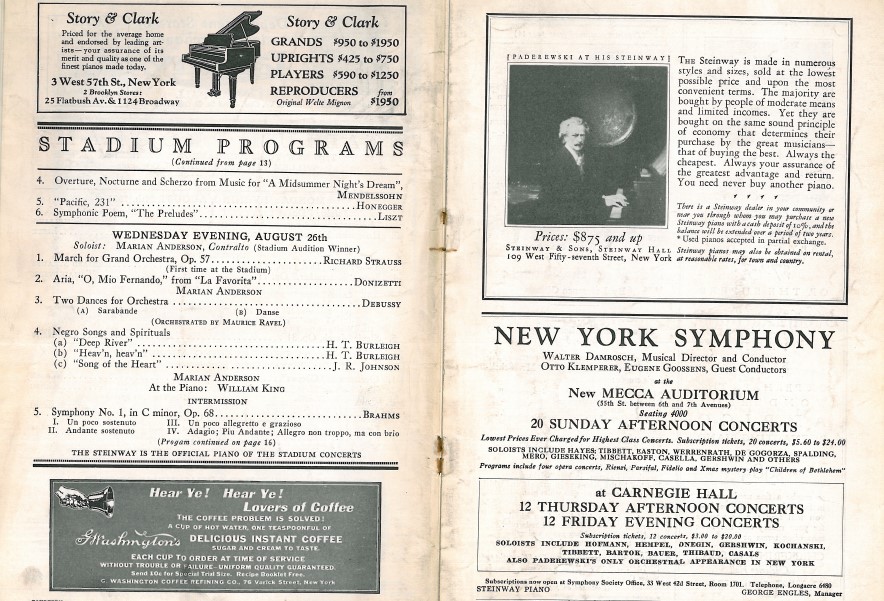

Whatever the motivation, Anderson performed “O mio Fernando” over and over at career-defining moments. She first studied it with Giuseppe Boghetti, an early teacher who was central to her development, and she leaned on it while trying to gain a foothold in a tough business. Her crucial early performances of “O mio Fernando” included her debut in 1924 in New York City’s Town Hall (a disappointment) and a now-famous contest sponsored in 1925 by the National Music League and the Stadium Concerts of the New York Philharmonic (a triumph). “Before my turn came, that song had been sung already six times,” Anderson recalled about hearing “O mio Fernando” as she waited to be called on the contest stage. “The teacher I was studying with then [Boghetti] had said no matter what the judges do—they have those little steel things that they make a noise with if they have heard enough—don’t you stop until you get to the end. At the end I had a trill which he thought wasn’t bad. Fortunately, they didn’t try to stop me.” Not only did the judges let her keep singing, but they chose her as one of 4 winners out of a pool of 300 contestants. The prize was a debut with the New York Philharmonic at an outdoor summertime concert in Lewisohn Stadium on August 26, 1925, where she delivered “O mio Fernando” to a mixed-race crowd of 7,500. That concert was a landmark date in the halting history of racial desegregation in the performance of classical music in the United States.

Lewisohn Stadium at City College. New York Philharmonic Archive.

Program for Marian Anderson’s debut at the Stadium Concerts, August 1925. New York Philharmonic Archive.

Anderson did not stop there with Donizetti’s aria, and a complete list of her performances would be long indeed. Some highlights: her first performance in Scandinavia in 1930, her legendary concert at the Lincoln Memorial in 1939, her debut solo recital in the old Metropolitan Opera House in 1943 (an event for which her manager rented the hall while she continued to be shut out by the opera company), and her debut with the New York Philharmonic in Carnegie Hall in 1946. There were many more. By the time she began her farewell tour in 1964 in her late sixties, Anderson had dropped “O mio Fernando” from the program. At that point, she had aged out of delivering a razzle-dazzle aria assigned to a character who is a sexy young mistress.

“There are some songs that I have been doing so often that I can see the printed music, though my eyes are closed,” Anderson wrote in her autobiography My Lord, What a Morning (1956). “O mio Fernando” was tops among them.

Selected Reference

Anderson interview quotations from: Barbara Klaw, “’A Voice One Hears Once in a Hundred Years’: An Interview with Marian Anderson,” American Heritage, 28 (February 1977), 50-57.