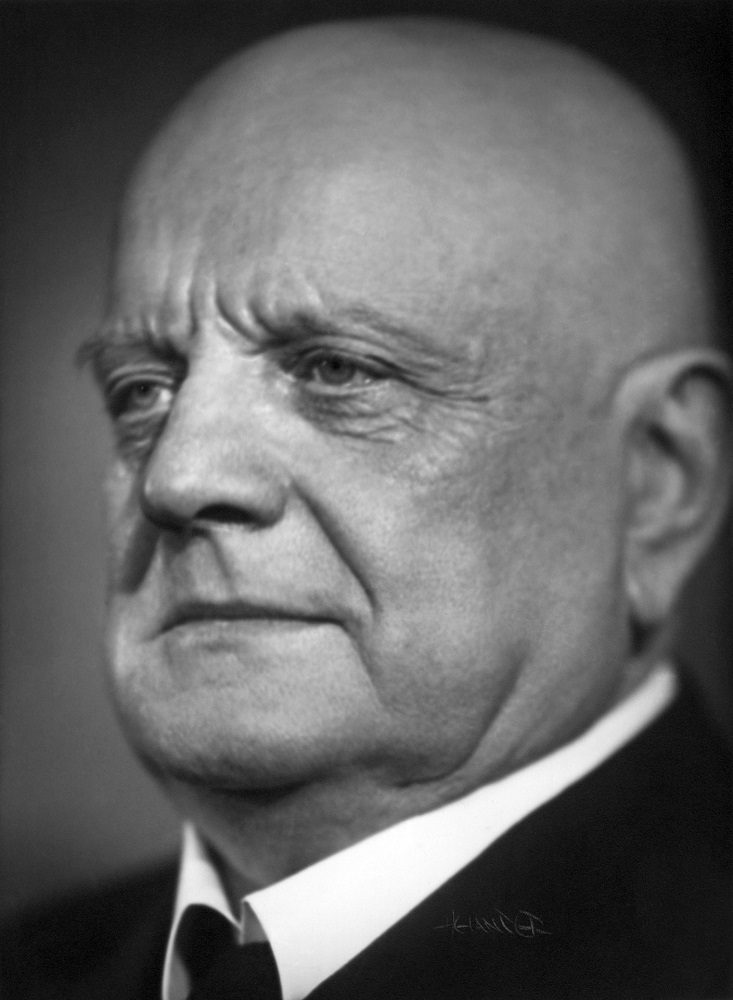

Philadelphia-born contralto Marian Anderson (1897–1993) is most remembered for her historic Easter Sunday recital on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in 1939. As a performer, she is closely associated with African American spirituals, which she described as “my own music,” and even with German lieder, especially by Schubert, “the composer I love best.” An unacknowledged and perhaps unexpected story line in her early career, however, is her embrace of the music of Finnish composer Jean Sibelius (1865–1957).

Marian Anderson Collection of Photographs, 1898-1992, Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts, University of Pennsylvania

In 1930, the 33-year-old Anderson embarked upon a tour of Scandinavia that marked the beginning of a special relationship with Norway, Sweden, Denmark, and Finland, where an insatiable fandom, characterized in local newspapers as “Marian fever,” elevated Anderson’s prestige on the continent, boosted her self-confidence, and pushed her into new artistic territory. Through Scandinavian connections, she met Finnish pianist Kosti Vehanen (1887–1957), who became her principal accompanist in the 1930s. Dedicated to promoting the music of fellow Finns, Vehanen introduced Anderson to Sibelius’s songs early in their collaboration. Though his reputation rests primarily on his orchestral music, Sibelius returned repeatedly to the composition of solo art songs, the majority in Swedish. He had a particular attachment to setting texts by Finland’s national poet Johan Ludvig Runeberg (1804–77), including “Flickan kom ifrån sin älsklings möte” (The girl returned from meeting her lover), which Sibelius published as the last of his Five Songs, op. 37. It remains one of his most often performed pieces in the genre. Yet because of language challenges, Sibelius’s songs have largely hovered at the margins of American vocal recital repertory.

Marian Anderson Collection of Photographs, 1898-1992, Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts, University of Pennsylvania

On November 13, 1931, Anderson and Vehanen visited the 65-year-old Sibelius’s wooded villa in Järvenpää, 25 miles north of Helsinki, to present some of songs they had been working on. Sibelius responded rapturously to Anderson’s performance of his music, calling for a round of champagne to celebrate. “The only criticism he had to offer,” Vehanen recalled, “was the suggestion, ‘More Marian Anderson and less Sibelius.’” The encounter was impactful for Anderson. She found one of the first Sibelius songs she learned, “Norden,” to be “beautiful,” though “also strange and so foreign to me that I could not quite grasp it.” After communing with Sibelius, she believed that she “had caught a deeper glimpse of the meaning” of this repertory. “It was as if a veil had been lifted,” she described in her autobiography, “and whenever I sang the songs of Sibelius again, I sensed that I was approaching them with fresh understanding.”

“Flickan kom ifrån sin älsklings möte” was not one of the songs that Anderson workshopped with Sibelius, though when she began to record his songs in February 1936—ten in all that year alone—it was among the very first she brought into the studio (on Feb. 6, accompanied by Vehanen). She became the first vocalist to record the song in Swedish. Runeberg’s poem unfolds as a series of mother-daughter conversations that at a deeper level capture an undercurrent of eroticism in the young girl’s emotional tangle of secretly awakened passion and lingering vulnerability. There are strong echoes of Tchaikovsky in the late romantic musical language of Sibelius’s piano part. The expansive melody offers glimpses of both the rich coloring of Anderson’s lower range—which extended another octave below—and her powerful upper register, heard at the song’s climax. Sibelius’s persistently declarative rendering of the dialogue-driven poem complements Anderson’s role as a nuanced storyteller whose voice progresses from the crisp brightness of the opening two stanzas, through the rising turmoil of the minor mode third stanza, to darker hues of resignation in the notably expressive final bars that suggest a regretful fall from innocence.

Anderson’s immersion in Sibelius’s music reflected her commitment to singing in the native language of her audience—even if it meant performing Brahms’s Alto Rhapsody translated into Hebrew, as she did during her 1955 tour of Israel. It also pointed the way toward Anderson’s long-overlooked contributions as a pioneering interpreter of Sibelius’s art songs, both within and beyond Scandinavia.