Pauline Viardot’s Missing Mörike Cycle

Can the editorial creation of a song-cycle from individual songs help raise the visibility of women composers? The songs of Pauline Viardot-Garcia offer a wonderful opportunity.

Music, Voice, Message

People who identify as women

WSF is an online forum devoted to women’s voices in song, to the many songs by women, and to the many female musicians working in and with song, who have yet to be given the attention they deserve. The Women’s Song Forum provides an opportunity to expand and enhance knowledge and understanding of this rich and significant area of musical practice and scholarship, and – as the name “forum” suggests – aims to encourage discussion and debate across different interest groups. The forum aims to highlight compositions and performances of music that deserve more recognition.

At the heart of the forum is our commitment to diverse approaches and subjects and access by a wide-ranging audience. We normally publish 2-3 posts each month by members of our team and guest bloggers.

Can the editorial creation of a song-cycle from individual songs help raise the visibility of women composers? The songs of Pauline Viardot-Garcia offer a wonderful opportunity.

Last summer I assembled a cycle of eight songs by the 19th-century German composer Pauline Decker, understanding this curatorial action as an important form of advocacy.

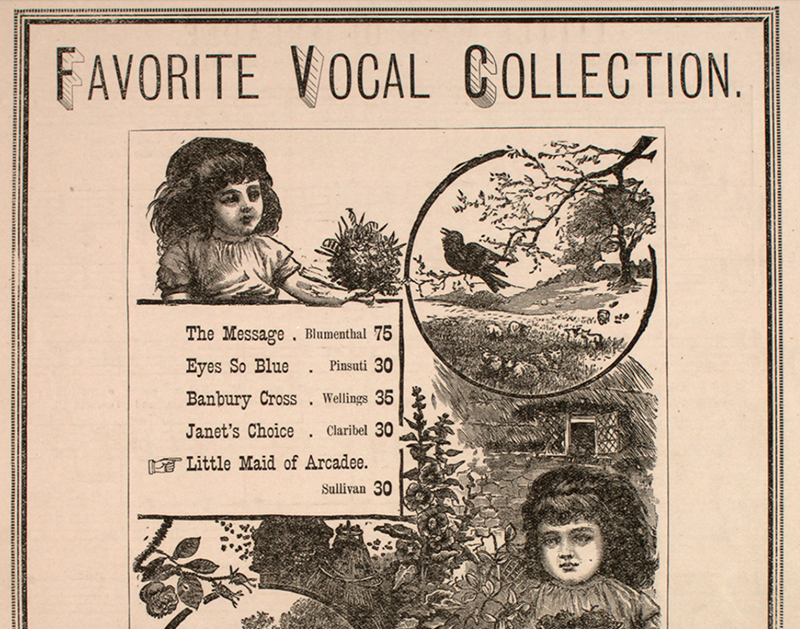

The Hal Leonard company has long sold an anthology entitled Daffodils, Violets & Snowflakes, 24 gender-stereotyped songs from 1900-22. Here’s a look at what they convey.

A century ago women composers in German-speaking countries often followed their male colleagues in preferring to set poems by men. But a few had other ideas.

When Italian singer Beniamino Gigli made his farewell tour of America in 1955, some three thousand people packed Carnegie Hall to hear his recitals. On

From accounts of individual women or performances to historical essays, from interviews with songwriters and performers to discussions of gender, race and culture in and through song.

Tracy Chapman

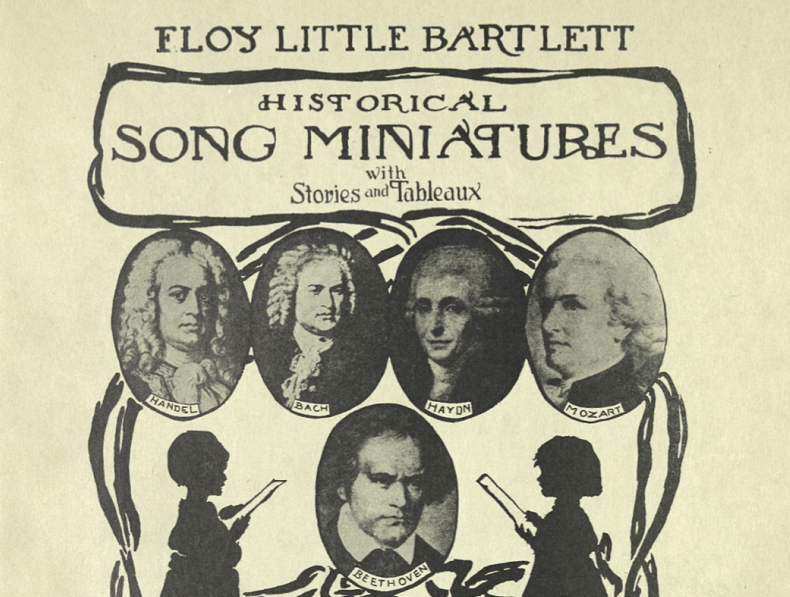

As European art music began to be challenged by jazz, musically influential women devised ways to cultivate “a taste for ‘good’ music in children.”

“Praying,” Kesha’s first ballad, was written about her recovery from traumatic abuse by her former producer, Dr. Luke. Her voice depicts this journey.

Lisa Colton recounts the thrill of discovering the autograph manuscript of Edith Smyth’s ‘Mass in D.’

Ascensión Mazuela-Anguita finds that Lomax’s 1952-53 recordings help us to understand the political situation under Franco, life in impoverished Spain, and the moral constrictions faced by women.

John Michael Cooper interprets Florence Price’s songs, “To My Little Son” and “Brown Arms (To Mother),” as responses to the painful losses of her son and her mother.

In her second post, Heather Platt tracks Villa Whitney White’s lecture-recitals of German lieder from 1895–98. Unusually, White sang complete song-cycles and songs written for men.

One of our aims is to recover and honor voices that have been overlooked or forgotten.

Sara Teasdale

Carrie Jacobs Bond’s world-wide hit, “A Perfect Day” (1910), was one of the most purchased, most sung, and most parodied songs for decades.

In her 2011 album Night of Hunters, Tori Amos reflects on a long tradition of classical music penned by men from the perspective of a woman.

Although banned for much of her career from major opera houses, Marian Anderson had an intriguing and lifelong devotion to Donizetti’s aria “O mio Fernando.”